Our topic is play. Before we begin discussing the five books you’ve cited, I thought it would be useful to establish what we mean when we talk about play. My three-year-old daughter offered the following definition: “Play is doing lots of stuff that’s fun, sometimes with friends.” Can you refine her definition? What is play?

Play is something you do for pleasure. It is not task-oriented; it’s not necessary. Some people refer to it as children’s business or children’s work. But I don’t think of it that way. I think of it as children exercising their inner self, imitating behaviours around them and acting out something that is new to them. In play, children miniaturise the world, reducing it to size within their intellectual grasp.

There are different forms of play. Physical play uses your hands, your muscles, your body to feel, touch, slide, run and ride a tricycle. Imaginative play begins around the age of 18 months – a child will take a teddy bear and pretend to feed it. Three-, four- and five-year-olds focus on imaginative play. As far as I’m concerned that’s the most charming age for a child. I love five-year-olds – their imaginations are in full blossom and they have the vocabulary for elaborate make-believe.

Is play just for kids?

No, we play all our lives. It takes different forms – adults play board games, organised sports or act in amateur theatre. Play goes on throughout life. We don’t lose the capacity or the need for play – it just takes different forms.

Is play just for humans?

No, animals play. Studies of animal life show chimps, cubs and young animals of all sort engage in rough and tumble tousling, which is not designed to hurt, it’s definitely play.

Each of the books you’ve cited helps us understand the benefits and uses of play. Let’s begin with the work of Kurt Lewin, the German-American founder of social psychology. What do you draw from his Dynamic Theory of Personality, first published in 1935?

When my husband was earning his dissertation, I took a course on learning theory and the instructor assigned A Dynamic Theory of Personality. By the time I finished it, I decided to switch career paths. I had wanted to be an archaeologist but Lewin’s work made me see that psychology is much more interesting. I wanted to deal with real life rather than old bones.

“In play, children miniaturise the world, reducing it to size within their intellectual grasp.”

Lewin is well known for a number of experiments that found people who worked in a democratic way were more productive. He conducted studies in factories that showed groups with autocratic leadership had much more aggression and hostility among workers. So democratic society tends to be more productive.

That was one aspect of his work. And he inspired a lot of work on integration, which led to my own dissertation, looking at what educational settings engendered tolerance – all white, all black or integrated schools. I found integrated schools were much more accepting than either all white or all black schools.

You’ve cited his work in your work on play. What does he teach about our topic?

When children play in a democratic way – in other words, when they share their ideas and decide on the direction of their play together – there is much more acceptance than when one child simply tells the rest what to do. Constructive play is cooperative play. If one child starts to get bossy and doesn’t allow others to voice their opinions, pretty soon the others don’t want to play with that child. Bossiness doesn’t really bode well for the game to continue. But if the leader listens to others and shows more fairness, play continues longer. Teachers can help this democratic play along if they listen and suggest alternative ways to play.

Does play teach us to be more cooperative and democratic?

Play has so many positive effects. When children play they become much more flexible. If they don’t have a particular object they need in their make-believe, they repurpose what they can find. For instance, if a child needs a horn for a pretend bus, he can grab a ball and make believe. So play builds nimbleness and creativity.

A great deal of research shows play enhances vocabulary. When children play they adopt new words. If they’re playing pirates and an adult gives them the words for eye patch, the words will stick with them.

The other thing that’s very important, as they play they’re learning self-control. They learn not to hit but instead to use words. They learn delayed gratification. You can’t have a tea party until you boil the water. Pretend preliminary steps teach them patience in real world interactions. So play has scores of positive effects.

Erik Erikson underscores “the fateful function of childhood in the fabric of society”. Please tell us about Erikson and the book you’ve cited, Childhood and Society.

Erikson was one of the first to outline stages of childhood. He identified eight stages. In the earliest stage an infant learns trust – trust that his mother, father and other caregivers will feed him when he’s hungry and change his diaper when he’s irritated. When your child learns to trust their immediate caregivers they generalise this good feeling to other adults, but when they learn mistrust they tend to be more suspicious of those around them.

In the second stage of early childhood, from the time they walk to roughly the third birthday, children learn about control – mastery of physical skills and control over their own toilet habits and their own impulses. Their caregivers teach them to wait for the bathroom and to use words instead of shoves. They begin to get a real sense of autonomy. This is why you hear a two-year-old or three-year-old say “no, no, no”.

Erikson’s third stage, the preschool years, about three to six, is when children really begin to have a sense of purpose. They try to exert their power; they’re more independent in the playground. As we move on to the school-age child, they begin to develop competence. From six to 11, school plays a very powerful role in a child’s life. Teachers really have to reward the child, rather than give them a sense of guilt or failure, which they could carry with them over long periods. So parents have to be alert to the perils of this period. Then we move on to adolescence.

Erikson extolled the importance of play. What did he have to say specifically on that subject?

Erikson is the one who pointed out that play is a way of resolving psychological conflict. In his book he cites examples. The one that I remember is a child who plays over and over with a box. His grandmother died and he didn’t quite know what a coffin was – he didn’t understand burial – but he re-enacted it through play. Erikson explained that the complexities of the world are explored through the microcosm of play.

He made one error that I think he retracted later. He thought that girls playing with blocks built enclosures and boys built towers, because of their own anatomy. In the beginning he was very influenced by Freud. Play patterns are not entirely dictated by gender. Girls play with boy things and vice versa. But it is difficult to get kids to cross over.

In advertisements, you’d never see a boy with a doll. It would be nice if nursery school teachers would say, “OK, today all the girls will play with the trucks and the blocks and the big cars, and all the boys are going to play with the dolls and the ironing boards and the kitchen stuff.”

That leads us to a book about play by Jean Piaget, Play, Dreams and Imitation in Childhood. You co-wrote A Piaget Primer with a colleague. Please give us a précis of the Swiss psychologist’s contributions to our understanding of childhood development.

Piaget proposed four major stages to childhood. The first stage of sensory motor development lasted from birth to age two. He observed that when babies play in their cribs and whack at a mobile, they’re learning through play. When they push, grab and shake things, they’re exploring the way the world works through play.

His second stage, he called it the preoperational stage, lasts from two to seven. During this stage children are learning to use words and images but they still can’t see abstractly. Piaget felt the concrete operational stage that followed, from seven to 11, was very important. Children begin developing knowledge and solving problems – that’s why they can begin to do their math or geography, they can begin to read. Finally, Piaget felt children would go on to the last stage, which is formal operation. Then they’re much more like adults – they can think abstractly; they’re interested in social issues and morality.

Piaget’s books evolved from his observations about his own children. He kept detailed records of everything his children did. Then he began working with children of age six, seven, eight or nine. His experiments generally were small in number but later on in his life he actually did have hundreds of children that he did research on.

Piaget developed a theory of play. Can you please outline it for us?

Sensory motor play was a big part of the first stage – touching, tossing and even putting objects in the mouth. It’s very physical. Then there’s practise play – a child attempts to climb something or open something over and over again until he becomes competent. And finally there’s imaginative play, where the child is able to assimilate ideas from the world and accommodate the concepts to the world of play. For example, using a broom as a hobbyhorse. That’s assimilation. When a child is playing he is assimilating information about the world in his own idiosyncratic way.

He also talks about play as compensatory. For example, an older sibling who hides a baby doll when a new child comes home from the hospital. It’s the elder child’s way of saying, “I really don’t want this younger one around.” So here is play as a way of self-healing.

That leads us to Frederick Allen, one of the forefathers of play therapy. You cited Psychotherapy With Children, first published in 1942. Please explain what this book teaches.

Allen established the general principle that the play a child chooses usually has something to do with what concerns them most in life. He also laid out some procedures, such as setting a regular time and establishing the child’s confidence in the confidentiality of the therapeutic relationship.

This is a very practical book that will tell you how to conduct play therapy with children – for instance, what you’d need in a room. Children tend not to be as verbal as you’d like. So you give them a chance to play with props or draw on a pad.

Allen and Virginia Axline, author of my next book choice, were both influential in my work. I got my degree at Columbia, where Axline had her clinical play lab. We learned to help children play, act and draw about their concerns and fears and how to interpret what the children would do and say. We used all sorts of modalities – dolls, puppets and all sorts of props – to help children express their feelings and help suggest alternative ways of handling them. For instance, I found that winning and losing at games such as checkers [draughts] could be a powerful therapy for children. I remember one particularly aggressive child overturned the board the first time he lost but after playing many games he learned to see that losing wasn’t the end of the world.

I also learned from Allen and Axline that parents are a very important part of the therapeutic process. If you are working with a child in play therapy you absolutely have to see the parent. I carried that into my own play therapy practice. After seeing the child, I’d see the parent to re-enforce what they were doing right or guide them toward different behaviour.

I also learned from Axline to connect with schools. That’s where a child spends a good deal of his or her time. So as part of my practice I’d go to the school to observe the interaction between the child and the peer group and the child and the teachers. Sometimes if the chemistry is not good, it can be difficult for the child. So I learned from Axline to offer myself to teachers as a collaborator in trying to do the best by the child. Visiting the schools, meeting with the parents, it all takes a lot of time. Child therapists work very hard. That’s why there aren’t many of them.

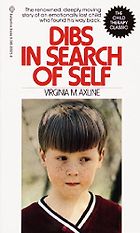

Finally, you cited a classic clinical narrative of child therapy, Dibs in Search of Self by Virginia Axline. Please tell us the story of Dibs.

This is a wonderful book. I’ve read it several times and it’s almost guaranteed to make you cry. Dibs came from an academic family that was well off. He was having trouble in school and his parents thought he was autistic. Axline accepted his idiosyncrasies and offered him a respectful outlet for his imagination and worked with the parents. They began to be more accepting of him and Dibs began to be more accepting of himself. It’s a small book, but very moving and very powerfully written.

What, more broadly, are the consequences of play deprivation?

Children that don’t get the opportunity for open-ended play don’t get any of the benefits we’ve been talking about. They don’t get the vocabulary, they don’t learn self-control, they lose out on imaginative life. They only know how to interact through rough and tumble play and so they become difficult to interact with in the schoolyard and hard to teach in class. The good news is that we can teach children play skills and we can see a significant difference after two weeks.

You wrote a book called Make-Believe designed to help teachers and parents foster play skills, develop life skills through play and solve problems through play. What are the benefits of play coaching?

The book offers parents and teachers of preschool children ideas for play. For example, we suggested a sensory shelf filled with little vials of different substances to help them develop their sense of smell. Each section of the book deals with a different sort of play. In a section on sociodynamic play we suggest props for pretending, and in a section on physical play we describe how to make an obstacle course out of your living room.

All the ideas came from a workshop we did with parents at Yale, so almost every one of those ideas was tested and tried out. We were distributing the ideas on mimeographed sheets and a parent suggested we put them together into a book.

In addition to dozens of ideas for play you also suggest some general guidelines.

We warn against being too invasive. That was based on research done in South Africa, which found that when you continuously play with the child you’re taking over and the child won’t get the full benefits of exercising their mind. Just start playing and then back out. Get the child started and then listen for when they get stuck and need a suggestion or could benefit from a new word such as a treasure chest for a pirate game.

Another suggestion is to give your child unstructured toys. Your child will be much better off with more blocks and fewer toys that entail batteries or remote controls. Children are best off with things that are open-ended – crayons, pads, dolls.

Another thing that we suggest is to take your child outdoors to experience the outside world. Look for birds. Smell the flowers. Turn over a rock and see what is beneath. There are few things that are more exciting and engrossing for a child.

Your most recent scholarship concerns how electronic media have narrowed imaginative breadth. Please brief us on your findings and their implications for play.

Studies are showing that children who are heavily into the Internet and television are less imaginative in their play. They don’t play the elaborate games that children who are lighter users of media construct. The more you rely on television for formulaic stories, rather than enacting your own story though the use of play and props, the less imaginative you will be.

Is neuroscience confirming the importance of play to neurogenesis?

It’s hard to do an MRI on a child who is playing, so we don’t have a database to speak with certainty, currently. But I’d suspect that when we do we’d see more activity when we play.

Are there any benefits that redound to adults who play?

Oh yes, studies show their minds become much more open, and seeing their children enjoying the benefits of play awakens the love of play in them. When your child plays imaginatively, the benefits carry over to you.

How does play affect society at large?

What a question! Maybe if we were a more playful society we could resolve some of the conflicts we have now. I don’t see a lot of cooperative behaviour in Congress. Maybe if they all had a romp together that could change.

Five Books aims to keep its book recommendations and interviews up to date. If you are the interviewee and would like to update your choice of books (or even just what you say about them) please email us at [email protected]

Five Books interviews are expensive to produce. If you've enjoyed this interview, please support us by donating a small amount.