What is the ‘zombie apocalypse’?

The zombie apocalypse is a narrative that can dated back to around 1968 when George A. Romero’s Night of the Living Dead came out. In its classic form, it’s a story about human-looking inhuman monsters who have been raised from the dead and have a strange power to transform the people that they attack into creatures like them.

It brings together many different narrative tropes: it’s an apocalyptic tale, a survival story, and a horror story.

“When things look desperate in the world, the dead get up and walk”

Zombie apocalypses have made an amazing resurgence in the post-9/11 west. What they seem to do is to provide us with a story that looks like the end of the world. We get a chance to evaluate what the characters in these stories do in order to try and survive, and what those decisions do to them in terms of their own humanity.

But it’s a highly malleable story, and zombies can stand in for many different kinds of menace. As well as international terrorism, the menace can be pandemics and viruses, political unrest, unrest in the markets, or violence in the streets. When things look desperate in the world, the dead get up and walk.

Friedrich Nietzsche suggested that religious apocalypse was the expression of a covert desire to see the world being destroyed. Whether or not we agree with his interpretation of religious apocalypse, do you think that a similar interpretation holds for the secular zombie apocalypse—that we can take pleasure in imagining the world being destroyed and overrun with zombies?

Yes. As many cultural critics have pointed out, the zombie apocalypse can be a highly entertaining story. Apparently there is a Walking Dead game that is played by twenty million people on Facebook.

I think there’s both a secular and a sacred element. What I do in my work is to try and bring these together and to look for the philosophical and religious meanings in secular literature and culture.

One of the things that zombie stories do is offer us a chance to critique our own culture. There has been more than one time—certainly thinking about recent elections—when I have thought that we should just wipe the slate clean and start over because I don’t see how things are going to improve. It feels like the end of the world, and we might as well just push it that little bit further.

But that’s the fun thing about zombie stories—as terrible as the world may seem to us at this moment, it’s not that terrible. No one is actually trying to eat us. I have not had to beat any creatures to death with a baseball bat just in order to stay alive for another twenty four hours. Zombie stories can be reassuring.

There’s a socially-critical aspect to some of George A. Romero’s films. I’m thinking particularly of Dawn of the Dead where you see zombies walking around a shopping mall with canned music playing: that seems a fairly thinly-veiled critique of consumer culture. Do you think that the zombie movies and books that have proliferated since Romero have become commodities that we consume in a zombie-like manner?

It’s true that we can consume zombie stories, and often uncritically. But I’ve based my whole career as a narratologist and theologian around the idea that even when we’re consuming narratives, we’re using them in some way. If many people drawn to particular stories, whether Harry Potter or The Walking Dead, these stories are working on us in some way to help us make meaning of some of the major issues in our lives.

So, I think that the lovely irony is that there are thousands of teenagers who like zombie movies and just love killing zombies on games consoles. And they’re not doing it because it’s a chance for them to examine their ethical choices; they’re doing it because it’s fun and they enjoy it.

But at the same time as this mindless consumption is going on, these stories are asking really serious questions. Questions about what’s the difference between us and them, for example. If, as human beings, we have the same tendency toward uncritical consumption as zombies, what makes us different from them?

Get the weekly Five Books newsletter

In many of these stories, there’s a moment of transformation in which someone turns into a zombie. This makes us think. In Shaun of the Dead when Shaun is arguing with his mother about his stepfather in the car, he says ‘there is nothing of the man that you remembered in that car’. That’s a pretty serious philosophical statement.

So, what I see my task as being is to take a look at the things that we tend to consume uncritically and to ask some critical questions so that people can be mindful about what’s contained in them.

Well, maybe we can tease out some of these critical questions with the five books that you have recommended. I was interested that the first book you chose was Richard Matheson’s I Am Legend because that is not, on the surface of it, a story about zombies.

Absolutely. The monsters in the book are more like vampires. But the interesting thing about I Am Legend is that it is an apocalyptic survival story. The main character thinks that he is the last human being left on earth.

One of the things that I discovered in the course of researching this topic is that zombie stories are not really about zombies any more than Harry Potter is about magic wands. The zombies are merely a background detail. They are a way for us to explore what happens to human beings when they are placed under incredible stress.

I think about this book as highly significant for zombie apocalypse for two reasons. The first is that George A. Romero was very clear that I Am Legend was a source for Night of the Living Dead. He was inspired by this story of a person who is menaced by supernatural monsters and is trying to retain his sanity and figure out how to remain human.

The second is that I had a chance to interview Mark Protosevich who was the original screenwriter on the Will Smith film I Am Legend. He also thinks of it very much as a zombie apocalypse story.

For Mark, there was an overriding question as he wrote the film about what it means to be a survivor. He did a lot of research about people who were in extreme survival situations. He talked with many people who were on death row, or in isolation in prisons. He asked them about their experience and what they did to retain their sanity.

That’s similar to the situation of Robert Neville in I am Legend.

Yes, in the movie he’s living boarded up in a brownstone house in New York. Every day, he makes the rounds and repairs the damage. In Mark’s film version, the hope that Robert Neville has is not that he’s going to find a cure for the virus, but that he’s going to find another human being.

The ending of the novel is much bleaker than the film version.

Yes, it is very bleak. In general, there the two sorts of endings you get with zombie apocalypse stories. The first is the nihilistic ending. It is the end of everything, and the human race is finished. We find that in some of the Romero movies, and in the novel I Am Legend.

In the second sort of ending—including the film version of I Am Legend—the human race is going to continue. Here, Tolkien’s concept of the ‘eucatastrophe’ is relevant: the idea that even in this disaster there is the possibility for human growth and change. Theologically, that’s what the apocalyptic narrative is about. It’s a sort of cosmic reboot. If you’re faithful and, frankly, lucky, then you will get to the other side and see the new world, whatever that is.

Thinking back to the ending of the novel, there’s a moment when Robert Neville switches perspective and sees himself as if he were a vampire. Can we learn from that?

It’s a very unusual ending in which he reflects on what he must appear like to the monsters he has been hunting. They were monsters for him and now he thinks about what he must be to them: a vengeful person who has sent so many of them to an early death—a second death.

You mentioned 9/11 and the spate of zombie narratives that followed. Perhaps there is a temptation for people to think that they are beset by a zombie apocalypse. Do you think the ending of the novel could be used as a way of rethinking the entire categories of good and evil, us and them?

I think it could. Robert Neville develops a strange sympathy with his antagonists. He reflects that although he thought that he was doing the right thing for his species, actually he might be the destroyer. This is unusual, because most zombie narratives don’t encourage us to question the difference between us and the monster.

“Robert Neville develops a strange sympathy with his antagonists…. This is unusual, because most zombie narratives don’t encourage us to question the difference between us and the monster”

The problem post-9/11 is that we tend to monsterise the people to whom we find ourselves opposed. Many of our large action spectacles encourage us to do that: the villains tend to be things that you can kill without feeling remorse. Think, for example, of the Ultrons in the Avengers films. We think of them as being soulless, and therefore when we destroy them we don’t take on the same sort of moral culpability as we would if we were to kill a human being or a sentient creature.

Ultimately though, zombie narratives are probably more useful when we think about human encounters in these stories. That’s where our opportunity to leap across boundaries and think about whether we’re going to encounter the other with compassion or violence arises.

Like I am Legend, Cormac McCarthy’s The Road is not a straightforward zombie story, although it is post-apocalyptic. Why did you chose it?

I noticed that my book Living with the Living Dead was reviewed on a zombie studies site the other day, and they were somewhat indignant that I included The Road on the grounds that there are no zombies in this book. And in a sense, they’re right. There is no creature that has been transformed by leaking chemicals or radioactive satellites. But, on the other hand, there are human beings who consume other humans and that informs the major conflicts of the book.

Five Books interviews are expensive to produce. If you're enjoying this interview, please support us by donating a small amount.

So, you’ve got a post-apocalyptic setting and you’ve got ethical quandaries for the main characters. There’s the sense of menace that permeates the zombie apocalypse. It’s not bad enough that they’re going to kill you, they’re also going to eat you.

What I love about this story is its literary quality. We tend to think of the zombie apocalypse as a low-culture, pulp phenomenon.

I suppose that a lot of the early zombie stories from the 1920s and 30s were pulp fiction.

Sure. Yet with The Road, we’ve got what is essentially a zombie apocalypse story that is also a Pulitzer Prize-winning novel.

Angela Kang, one of the writers and executive producers of The Walking Dead, told me that she is not interested in zombies per se, but in human beings and what they are willing to do to survive.

In The Road, the man and the boy stand in for every human in every zombie apocalypse story. What are they willing to do to survive? What do they do in terms of their resources? Do they share them or do they hoard them? In the contacts that they make with other human beings, do they react with fear or do they react with welcome?

It’s such a beautifully written book, although highly fraught. You’ve got a great artist who wants to ask some universal human questions. By the time you come to the end of that novel, you have really explored what it’s like to live in a world where human beings are beset by threats coming from all directions.

As we look at the world at this moment, I can say that I personally as an American don’t want to respond to every threat by building walls. But that’s a choice that some people make. The father in this story basically says that all he cares about is his son’s survival, and he is not going to share anything that they have. That is an ethical choice that some people make. It’s an ethical choice that the United States made after 9/11: basically, the US held that it would do some unpleasant things in order to increase its chance of survival.

The son also faces difficult ethical questions.

The son is a marvellous character because in his innocence he is constantly checking his father. He keeps asking his father whether they are good—whether they are the good guys. The father comes up with a sort of pseudo-religious construct: that they are ‘carrying the fire’.

If you were in a George Miller Mad Max apocalypse story, and if you saw someone coming down the road towards you, you should probably turn and run in the other direction. But the son keeps asking the question: are we the good guys? In encounter after encounter, they make choices that are very narrowly focussed on themselves.

“Parallel ethical questions that we need to ask ourselves post-9/11 are: how do we relate to the other people or cultures that we have to encounter? Do we react to them with fear because we have encountered some people who are frightening?”

Parallel ethical questions that we need to ask ourselves post-9/11 are: how do we relate to the other people or cultures that we have to encounter? Do we react to them with fear because we have encountered some people who are frightening? Or do we react to them with compassion and generosity, because people may be more well-disposed towards us if we treat them with kindness?

Another kind of ethical question explored in The Road has to do with why we are here. The father explicitly says that he has been appointed by God to take care of his son, and that if anyone tries to touch his son he will kill them.

The son, in his innocence, is basically pushing back and giving the answer that we get from many of the great wisdom traditions as well as from moral atheism, which is that if he is the most important thing on the planet, then the planet is probably worthless.

This position is that there has got to be something more important than me and my desires and my life. I want to live for something more than that and I want to believe that there is something bigger than me.

I was interested that you described the phrase ‘carrying the fire’ as pseudo-religious. Would you resist a straightforward Christian reading of The Road?

Well, I am sure that there are some Catholic critics who do that because McCarthy was raised Catholic and you cannot shed it. I was raised Southern Baptist, which is conservative evangelical Christian, and however far to the left I go in terms of my own faith and cultural beliefs, there is still some part of me that knows all of the verses to ‘Amazing Grace’.

I think one of the things that makes the image of carrying the fire so wonderful is that it can be applied to a range of different traditions. If we read it as straight Christian, we might want to think of it in terms of some of the New Testament ideas around community.

At the end of the book, the question becomes: are we going to be like this isolated dyad going through whatever is left of our lives together, or are we going to open ourselves up to the possibility that we could be part of a larger community? What McCarthy does in a very faintly hopeful way is to come down on the side of larger community.

In his introduction to The Walking Dead, Robert Kirkman writes that he wants to explore how people deal with extreme situations and how these events change them. Is character development very important in this series?

I think it is important. From a narratological point of view, what Kirkman is pointing out here is that the zombie apocalypse becomes a genre in which we have a laboratory of human behaviour ramped up. We get a similar effect in war stories. What this scenario does is ratchet up our everyday normal human behaviour to force ten levels. It allows us to ask those really challenging questions about character in a much more rapid way.

Character is important because both the comic and TV series are long-form narratives in which you have the chance to develop binding relationships with characters. That, actually, for me is the hardest thing about watching both The Walking Dead and Game of Thrones: you get attached to characters who then get killed off. Eventually I stopped reading The Walking Dead because I did not want to get my heart broken anymore!

I suppose one major character who does survive is Rick Grimes. Can you tell us about him?

Yes. He starts out as a sort of proto-typical American Gary Cooper good guy—an ‘ah shucks’ lawman from a small sheriff’s department. Over the course of the story, he develops in response to the world of threat but also in response to the new responsibilities that he takes on. Some of those changes are positive, others less so.

For example, fans often talk about an iteration of Rick whom they call the ‘Ricktator’. He is basically the pragmatic leader of the group willing to do violence or whatever is necessary to protect the group and keep them together. This is the version that we’ve seen mostly in recent seasons.

“What this scenario does is ratchet up our everyday normal human behaviour to force ten levels – it allows us to ask those really challenging questions about character in a much more rapid way”

In some ways, I really miss the naïve original Rick. There’s a moment in the beginning of The Walking Dead where he encounters one of the zombies—the first walkers—who has been so badly ravaged that she’s just lying helplessly in the grass making zombie noises. Rick takes her bike and rides back to his old home but before he leaves town, he comes back and kills her out of mercy. He was reacting to her helplessness and what he perceived as their shared humanity.

Of course, this is still very early in his understanding of what the walkers are. Later on, such killings just become reflex.

In Living with the Living Dead, you offer an interpretation of zombie culture from a broadly Christian or wisdom tradition perspective. Early in The Walking Dead, Rick walks into a church and sees some walkers sitting in the pews as if they were praying. Do you think that the suggestion here might be that Christianity is an opiate that is turning people into zombies?

We come back here to what we were talking about with the early George A. Romero films. Actually, it’s a trope that extends throughout The Walking Dead: that we are like the walkers if we are not living mindful lives or if we are sunk into old ways of seeing or being.

There’s another scene early in the series in which Rick encounters a family of evangelical Christians who have committed suicide. Basically, what has happened is that their faith could not accommodate the shock of the event. They had a very particular way of waiting for the second coming of Christ, and this was not the way the world should end. And if the Bible was wrong about that, then what else might it be wrong about?

I think it’s entirely possible that these scenes are intended to be a social commentary on the unthinking kind of faith that some people have. But the lovely thing about the scene in the church is that Rick recognises the connection to the figure of Jesus. He comes back in after they have cleaned up the church and he says that he doesn’t know how to pray, but he knows that he can talk about how to do the right thing and how difficult that is as a leader.

Can you tell us about Max Brooks’ World War Z?

Initially, your readers should be aware that it is extremely different from the blockbuster film with Brad Pitt. The underlying concept is the same, and the film retains some of the globetrotting elements, but otherwise the two are very different. In my opinion, the book is far superior.

One of the reasons I chose World War Z is that it is a novel that bridges the gap between pulp and high literature. It takes a subject matter which we would think of as mainstream geek culture, but it finds universal human themes, develops characters that you care about, and also manages to be culturally critical. It is clearly critical of many of the post-9/11 choices made by the United States and Britain.

The novel is an oral history of the zombie war, and it really does range the globe. There is no single narrative line running through the book. Rather, you have to piece the oral histories together like a collage to come to some kind of understanding of what has happened to the world.

That is the genius of using this low culture trope: we know what happens in a zombie apocalypse. We don’t have to be told every seminal event in that narrative. We talk to people who are largely on the periphery of the story. There is a lovely effect like those achieved by modernists like James Joyce or Virginia Woolf in which you have a chapter from one character’s point of view, and then another chapter from another character’s point of view. You are putting together thirteen ways of looking at a blackbird.

Am I right in thinking that the various accounts are complied by an investigative journalist?

The narrator – or compiler – of World War Z is a cultural historian who works for the United Nations. He is trying to talk to people and gather their stories in the same way that an oral historian might put together a history of the Blitz, or a history of the war in the South Pacific.

What is the significance of the global scope of the story?

I think one of the things that Brooks is trying to do is to explore what a true world war would look like. Even during the First World War, there were whole swathes of the world that were not involved.

In Brooks’s novel, the war starts in China but there are islands in the middle of the pacific which had to deal with zombies coming up out of the sea. Then there’s Cuba which became a world power as a result of decisions that they made during the course of the conflict.

There are two episodes that are set in Japan. The Japanese islands were largely evacuated during the zombie apocalypse, except for two people who stay behind. One of these is a sort of Hong Kong action-figure character: he’s a blind gardener who becomes a zombie killer with his spade. Along with his apprentice, he takes on the task of cleansing the Japanese isles so that the garden will be restored.

There’s a kind of universality about the situation. Everybody on the planet has to deal with the threat. I think that Brooks is suggesting that we are so much more alike than we are different.

So this story could almost form a model for a kind of global political consciousness?

Yes. And if we think of it as an anti-American post-9/11 narrative, one of the things that it does is say that there is a value to globalism and cooperation and pulling together, as opposed to the response we took to our own perceived apocalypse.

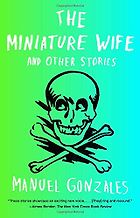

Your last selection is Manuel Gonzales’ The Miniature Wife: And Other Stories.

Manuel Gonzales is a Texan writer who lived in Austin for many years. He’s a very literary writer, but he mines fantasy and science fiction tropes for their narrative value.

There are a number of different kinds of stories collected in The Miniature Wife. The title story is about a man who in the course of his scientific experiments accidentally shrinks his wife. You have seen that in movies, or the converse where she’s a fifty-foot woman. He takes this science fiction trope and turns it into a relation story about what happens when relationships go bad.

That’s essentially what he’s doing with all of these stories. He’s taking seriously what we might think of as conflicts that you might deal with in a literary short story.

There are two zombie stories in the collection that I think are worth noting. One is told from the perspective of the zombie. We rarely get that perspective because, traditionally at least, the zombie is an unthinking non-sentient being whose only impulses are to feed. But there are some characters, for example in the Marvel Zombies, where they have sentience but they are also affected by this powerful overwhelming hunger. That’s what Manuel Gonzales does in this story told from a zombie’s point of view.

“We rarely get the zombie perspective because, traditionally at least, the zombie is an unthinking non-sentient being whose only impulses are to feed”

In some sense, it’s a sort of workplace romance: he’s in love with the woman in his office and he’s a zombie. He wants to love her and yet he is constantly fighting these impulses to eat people’s faces. It’s funny, charming, and heart-breaking.

Perhaps the most important story in this collection is ‘Escape From the Mall’. It takes us back to the Dawn of the Dead story and the remake, both of which are set in shopping malls. The narrator in this story is just an ordinary guy who is caught up in the zombie apocalypse. He and a couple of other people have escaped into a janitor’s closet.

The zombies are outside pounding to get in. He is talking with this guy who is the leader of the group and the guy has told him that he thinks that one of them is a zombie. So, you’ve got the enemy outside and the enemy inside.

At the end of ‘Escape From the Mall’, the main character has a long monologue where he says that he thinks that we need the end of the world because without it we can’t know who we are and how we are supposed to be. It’s similar to Tolkein’s idea of the eucatastrophe where the world has changed but people who have survived have changed along with this disaster. Now, perhaps, we can be the people that we are supposed to be in whatever this new world looks like.

I’m fascinated by this idea of ‘eucatastrophe’. Could you generalise that to a reading strategy for works of zombie apocalypse? Could it be a way of finding hope in these sometimes bleak stories?

Yes. It’s one of the things that lets me watch Game of Thrones and The Walking Dead even knowing that there are going to be casualties along the way. This is not precisely how Tolkien means it because in ‘On Fairy Stories’ he’s thinking largely about cosmic change: the new heaven and the new earth, in terms of the Christian understanding of what the apocalypse brings.

But the simple fact of being presented with these incredible challenges allows characters to grow and change and become something that they could not have been when they were sunk in their zombie-like lives.

One obvious example is Shaun in Shaun of the Dead. It’s made clear early on that there is very little difference between Shaun’s circle of friends and the zombies who are going to show up later. Shaun’s girlfriend says that they’re not really living but do the same thing over and over again and they are stuck in their lives.

In that story, because of the apocalypse, Shaun becomes the friend, the son, the boyfriend and the human being that he’s supposed to be. There are a couple of things that he’s chalked on his note-board in the kitchen and one of them is ‘sort life out’. So, Shaun of the dead stops being Shaun of the dead and becomes Shaun of the living.

That’s true of many characters who live through the zombie apocalypse. When we’re first introduced to Daryl in The Walking Dead, he’s violent and brutish and a loner. But during the course of the story, because of these challenges that he’s faced with, he becomes a friend, brother, leader, and a compassionate person.

Cultural critics talk about the idea of a reboot. Robert Kirkman says of The Walking Dead that in a world where the dead walk, we have to learn to live. We can think in terms of a cosmic reboot as well. It’s not enough for us just to be sunk in our unthinking mindlessness and it’s not enough for us to consume. We’ve got to become truly human.

The great Christian thinker Irenaeus talks about the glory of God as a human being fully alive. You don’t have to be a religious person to understand that that’s our calling. And that’s what happens in these zombie stories when we don’t all die.

Five Books aims to keep its book recommendations and interviews up to date. If you are the interviewee and would like to update your choice of books (or even just what you say about them) please email us at [email protected]