Tell me about your first choice, Out of Eden: Adam and Eve and the problem of Evil by Paul W Kahn.

The question concerning the nature of evil is a longstanding one but I would go so far as to say that in this profound book, the philosopher Paul Kahn has gone a very long way in answering it. He argues that in our secular age we have given reason such a dominant place in our understanding of modern politics that we can only understand evil acts by individuals or nations as deficits of rationality. If the Hutus were simply rational, they wouldn’t have killed the Tutsis, and so forth. Thus, our response to what we see as evil takes an essentially pedagogical form. We first try therapy to increase the malefactor’s rational capacity, and when that fails, we turn to legal punishment. But this leaves us with no conceptual framework for distinguishing between the simply bad act and the evil one. In short, secularism has no explanation of evil.

Kahn, who, over his last several books, has been working to articulate what he calls a political theology of modernity, fills that void with his own compelling explanation of the existential origin of evil: evil is the refusal to acknowledge and confront our own mortality. The murderer is the person who tries to avoid the inevitability of his own death by taking the power of life into his hands. Such an avoidance and its resulting violence is not limited to physical abuse or attacks. There is evil inside marriages and families whenever one person tries to crush another mentally in order to ward off a sense of his or her own entrapment in a dying body, ‘a wasting asset’, as Kahn calls it, ‘pregnant with non-being’. Thus, evil and love exist always in close proximity.

Modern politics tries to cabin love and evil as the realm of private life and psychopathology, respectively. But what Kahn shows brilliantly is how quixotic this effort is, because popular sovereigns, just like kings and emperors, still demand allegiance and the sacrifice of their citizens in war if necessary to sustain the state. And ultimately these are not rational choices but acts of love for country that often result in what others regard as acts of evil visited upon them.

It’s difficult to do the book justice in such a short space because it not only raises but brilliantly explores some of the deepest issues of human meaning and political life.

Disowning Knowledge by Stanley Cavell.

Stanley Cavell is a philosopher who has written a series of essays in this book on plays written by Shakespeare. At the centre of the book is an essay on King Lear called ‘The Avoidance of Love’. What I find so compelling about it is that it offers a reading of that play which really strikes at the core of everyday experience. He says the reason that King Lear rejects Cordelia in the first scene is not because she’s failed to give him the kind of showy demonstration of love that her sisters did, but that, in fact, she showed him real affection by being honest and clear.

What he can’t stand is the evidence of someone’s actual love and actual call to intimacy. The evil that is at work is the inability to tolerate another person’s recognition of one’s own humanity and mortality. He prefers the false coin of Regan and Goneril’s affections. I think that this is a compelling reading of the play. Cavell also explains why Edmund doesn’t reveal his identity to Gloucester while he is leading his blind father across the heath. To be recognised by his father at that moment would make clear his own lack of trust in him, having not gone to him at the outset of the play to ask about Edmund’s claims about their father.

Do you see this inability to let people get close as a common human trait? For example, I think there are similar types of characters in your book, Union Atlantic, with the 21st-century hard-nosed power-hungry New Yorkers.

Yes, there is a lot in the book about people who are avoiding being recognised by each other. They are not literally in disguise but intimacy is difficult to receive and when it is offered it is sometimes more of a threat than something which people can readily accept.

Let’s move on to Moby-Dick by Herman Melville.

Paul Kahn’s book suggests that evil derives from the violent avoidance of the realisation of our own mortality and there could be few better examples of this in literature than Melville’s portrait of Ahab in Moby-Dick. On first appearance the evil Ahab represents would seem to be that of obsession and delusion: he’s unable to let go of his need for revenge against the great white whale that took his leg from him and he’s willing to risk the lives of his men to taste that revenge. But the wound, of course, is about more than a missing limb. The whale has robbed him of his own sense of deathlessness and mastery over his world and he would sooner die trying to avoid that recognition than accept it. Others will be caught up by and killed in that very avoidance. The blindness of the powerful is always more dangerous than the blindness of the powerless.

What sets Moby-Dick apart and makes it a great work of literature is that, like Milton in Paradise Lost, Melville paints his villain with such a richness of language that the portrait becomes a kind of celebration of the figure despite his actions. The entire adventure is bathed in reverence for the natural world through which Ahab, Ishmael and the rest of the sailors move. Ishmael’s descriptions sing with awe for the ocean and the whales. And in this light Ahab’s fixation, however distorting it is of life, comes to be seen as a kind of respect for the majesty of the creature he’s pursuing. And so there is nothing simple about his avoidance. It has its own dark dignity. Again, as Kahn points out, evil and love are deeply intertwined.

Your next choice is very pertinent – this is Crude World: The Violent Twilight of Oil by Peter Maass.

Yes, this was written before the spill in the Gulf but it is a very well-written and detailed account of how countries have been affected and infected by the oil industry and how their politics have been distorted. It covers places like Saudi Arabia, Nigeria, New Guinea and Ecuador.

They are all places where, particularly with those last three, the power of the corporations is larger and more organised than the structure of governance. It shows the way in which business of that scale, even if practised under what passes for law in those countries, ends up as corruption. So there is this evil of greed and disequilibrium of one substance taking over an entire economy and the effects that has on the possibility of any other kind of development.

What is interesting to me is how different countries deal with this situation. It is so different in Africa to, say, in the United Arab Emirates or in other places where populations are less dense and the existing clan structure means the wealth is spread through a somewhat larger network of people; of course, those people then hire millions of guest workers to perform the labour of their budding service economies, and that creates a different, more nominally legal form of exploitation and neglect.

Do you think the reaction to the BP oil spill is very different because it has happened in the US rather than in a country like Nigeria?

It is certainly true that press coverage changes everything so that the amount of attention it gets is a function of how much media the US has to spend on it. But I think the quantities are so high at the moment that it’s difficult to overestimate the long-term consequences of this event.

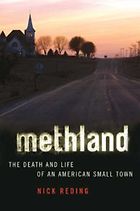

Your last book is Nick Reding’s Methland: The Death and Life of An American Small Town.

This is a book which I have just finished reading. I don’t know how much methamphetamine there is in Britain. It’s a drug that in World War II was used by soldiers on both sides of the war in milder doses. It is basically something that keeps you awake and charged up and gives you a high. This book is an account of how it has become a plague of sorts in American farming communities.

There are many reasons for this: the massive consolidation of the farming industry in the last 30 years, increasing dependence on illegal immigrants from Mexico for things like meat-packing, Mexico being the place where most meth is now produced. The drug has really rotted away towns that were already damaged by unemployment and lower educational levels.

What is strange is that it has such a different profile from the way that Americans are used to thinking about drugs. Normally drugs are associated with urban communities, primarily African-Americans. The vast majority of meth users are white, it is out in these rural communities and for a long time, unlike other drugs, much of it was produced domestically. It’s an awfully damaging drug which burns people out very quickly and destructively and is highly addictive. It began as a working-class drug to keep people awake but now it is sold in much more potent, pure form for the high rather than the ability to concentrate.

With these five books we have looked at the many different faces of evil. What fascinates you about evil as a subject?

As you may be able to tell from my descriptions, it was Out of Eden that got me thinking about it most forcefully. It echoed Stanley Cavell’s point about the avoidance of love as a source of evil, and it made it clear that we really don’t have a coherent way of conceptualising evil in our secular, rationalist culture. And yet we all have an intuition that there is such a category of action, something that exceeds mere bad behaviour or selfishness. Hannah Arendt’s thesis that at the bottom of evil lies banality seems too thin a description of the phenomenon to account for its psychological force. It’s a messier business, more closely tied to everyday life. And to that extent I suppose these books represent more than anything what I’ve been dwelling on lately, perhaps in preparation for what I’ll write next.

July 25, 2010. Updated: December 2, 2023

Five Books aims to keep its book recommendations and interviews up to date. If you are the interviewee and would like to update your choice of books (or even just what you say about them) please email us at [email protected]

Five Books interviews are expensive to produce. If you've enjoyed this interview, please support us by donating a small amount.