Fantasy graphic novels are enormously popular. Why is this such a good form for fantasy?

There’s almost always an element of fantasy in graphic stories. I think the two go together very felicitously. It’s so easy to immerse a reader in a fantasy world if you’re able to present it in visuals. Most of the books I’ve chosen are books that do that; they take you into alternate realities that are wildly different from our own, and make you feel like you’re living in them. Which is, I think, one of the most exciting and rewarding things that any story can do.

Do you ever find yourself coming up against a fantasy concept you can’t use in a graphic novel, because of the visual representation?

There are some, yes! I did a series of supernatural noir thrillers starring an exorcist named Felix Castor. He’s an exorcist, but he walks the mean streets and he wears a trench coat – he’s very much a Raymond Chandler or Dashiell Hammett style knight-without-armour in a savage world. But he exorcises ghosts with music. He has a tin whistle, and when he’s in the presence of a ghost, he hears the tune that represents them. He can play the tune and tangle the ghost up in it in such a way that it’s driven out of this reality into another one. I wouldn’t know how to begin to show that in a comic.

There’s a character in X-Men called Dazzler, whose powers are sonic powers. She uses music to fight. Nobody’s ever been able to make that work on the page.

Let’s talk about your first choice, Carla Speed McNeil’s Finder: Talisman.

Finder is still the core of Carla Speed McNeil’s work. Along with her partner, she created her own imprint, Lightspeed Press, in order to publish it. It dates to the 1980s and 1990s – most of my choices are classics, in the sense that they’re pre- the turn of the millennium. No apology for that! If I was going to do a contemporary series, or contemporary choices, it would be very different…

Ah, maybe we could talk about that later!

Yes! So Finder is a book that I discovered when it was still coming out in single issues. What makes it so wonderful is that it never ever stops to explain itself; it lets the world just gradually take shape around you. There’s nothing in the way of exegesis, no verbal explanation of how this world came to be. It’s obvious that it’s in the far future of our world, and that it’s very sparsely populated compared to our world, but not really post-apocalyptic. There are cities, and there are people who live in the cities and who have a relatively high-tech lifestyle. And then there are spaces between the cities which are inhabited by many different kinds of beings, human and non-human.

The lead character is a man named Jaeger Ayers, and he is equally at home in the cities and out in the wilderness. His father was a city dweller, his mother was ‘Ascian’ – the Ascians are Native American coded. I said he’s at home in both places, but he’s also kind of an outsider in both places; his mixed-race heritage makes him stand out. It gives him an exoticism in the city, but when he’s outside, in the wilderness, he’s not really accepted as being of his mother’s caste. But he does have a place in Ascian society: he is a Finder. If you ask him to find someone or something, he will do it. He has incredible tracking skills. And he’s also a ‘sin-eater’: he will take on the blame for other people’s misdeeds in ritual expiations.

“It’s so easy to immerse a reader in a fantasy world if you’re able to present it in visuals”

Around him, Speed McNeil assembles this enormous cast of fascinating characters. The first two collections of Finder were largely about Jaeger’s relationship with a family: Emma Lockhart and her three daughters (one of one of the three daughters is biologically male), and her abusive husband, Brigham. And Jaeger is put in the predicament of standing between this very violent, unstable man, and the family that he’s trying to reconnect with.

Talisman is different. Talisman is about the youngest of those three Lockhart girls, Marcie. And it’s about a book. It’s a book that she had when she was a very little girl; Jaeger gives it to her. Because she can’t read at that time, he reads stories from the book to her, over a space of years. They light up the inside of her head: marvellous, wonderful stories. And then she loses the book – actually, her mother throws the book out, thinking it’s rubbish.

Marcie tries very, very hard to find the book again; and Talisman is about that process, about her quest for the book. She finally has the realisation that if she can’t find it, she will have to remake it: you have to write the book that you need, you have to be the fulfilment of your own quest. But along the way, it’s just such a wonderful celebration of the power of story, and the role of imagination in our lives. It’s my favourite of these Finder collections, and it’s the smallest – it’s only 60 or 70 pages. But it’s just a magical story full of indelible characters.

Do these books stand alone?

They’re best read in sequence, because McNeil tends to pay things off unexpectedly in later volumes. So Brigham is introduced in the first story, and then Brigham’s relationship with the Lockhart family plays through quite a few of the later books… Some of them are standalones. But I would recommend reading the two big omnibus collections, Finder Library volumes one and two.

In this case, we have a single author-illustrator, which is more common on your list today than collaborations. Is that representative?

It depends. In the American mainstream, if you look at DC and Marvel, it’s far more usual to have a team – a writer, a penciller, an inker, a colourist, a letterer. A comic is the coming together of all those different skill sets. But in the independent scene, it’s very, very common to have writer-artists. And you’re right, most of the books I’ve chosen are in that tradition. The Sandman is the exception.

Yes, and that’s your next choice! Specifically the fourth in the series, The Sandman: Season of Mists, by Neil Gaiman and four illustrators. Could you introduce us to this one?

Yes. In some ways, Sandman needs no introduction; it’s become a massive cultural phenomenon, recently dramatised on Netflix. I was reading it in issue form when it first came out; it was Neil Gaiman’s spectacular entry into the mainstream comic scene in 1989. There was previously a superhero character in the DC universe called the Sandman, a man named Wesley Dodds who fought crime, and had a little gun that fired gas and put his enemies to sleep. Karen Berger, who was the editor Gaiman worked with mostly at DC, encouraged him to create a new character of his own rather than try to reinvent this 1970s character. So we got the character of Morpheus, Dream of the Endless.

The Endless are a family of siblings, who are at one point called ideas clothed in flesh. They are aspects of human experience: Dream, Delirium (who used to be Delight),Desire, Despair, Death, Destiny – and then there is the seventh brother, ‘The Prodigal’, who makes a late entry to the scene – he’s missing at the start of the story. The Endless stand outside any human pantheon, and to a large extent they stand above the gods. They are incarnations of certain human universals. And in creating the book, Gaiman created a mythology that brought together all existing human mythologies. So along the way in The Sandman you get Japanese storm gods, you get the Norse pantheon, you get Bas from the Egyptian pantheon, you get Judeo-Christian angels and demons… and it all makes sense! It all comes together in a way that is wonderful and strange and utterly unique.

Five Books interviews are expensive to produce. If you're enjoying this interview, please support us by donating a small amount.

The other thing I love about Sandman is that it created a new template for comic storytelling. Up to that point American mainstream comics, the DC and Marvel world, were episodic. They were like soap operas with people in tights, in that nothing ever changed – the stories went on and on, but the status quo never advanced. Neil brought a novelistic approach to mainstream comics. Sandman is finite: it plays out over 75 issues – there were some miniseries attached, and he’s revisited it since in a free-standing graphic novel called The Dream Hunters, and in a prequel series – but it reaches a finite end point. It has this wondrously interwoven structure. It consists of alternating long stories, story arcs, and single issues, short stories that are twenty pages long. But they feed back into the main continuity unexpectedly from different angles.

I chose Season of Mist because it’s my favourite of the books. It’s the book in which Morpheus decides he has to go to hell and have a fight with Lucifer. A long time ago, Morpheus had a human romantic partner, a woman he loved named Nada; and he condemned her to hell when she refused to stay with him. He’s realised – belatedly – that this was an awful thing to do, so he’s going back to hell to free her, but obviously, Lucifer is not going to stand for that. The thing is, Morpheus can’t win this fight. Lucifer is much, much more powerful than him. So Morpheus is going, he assumes, to his death… And that’s not how the story plays out. The story is incredibly complex and unexpected, wrong-footing you with every turn. It introduces a lot of the characters who became long-running favourites in the series… It’s the first time in the series that you meet the Norse god Loki, and the first time you meet the Dead Boy Detectives, who have now got their own series.

It’s just an amazing horror fantasy, with some stunning surprises, and characters who are wonderful to spend time with.

You went on to write the series Lucifer, set in this universe and based on this Lucifer…

Yeah! So, small spoiler: in the course of this story Lucifer quits. He decides he doesn’t want to be ruler of hell anymore, because he realises that his rebellion against God has ended up with him doing God’s dirty work. He’s still part of the scheme. So he walks away from it. My series chronicles what happened after that: his quest for self-determination, his quest to escape from divine providence and be his own his own boss, which in some ways is impossible. Every child wants to break away from parental influence, but when your dad is God, it’s particularly problematic. I love Sandman, and being able to write those characters and add stories to that continuity was amazing.

Did that process give you a new perspective on Season of Mist?

I’d already read it and reread it endlessly, and the wonderful thing is that I always find new things when I come back to it. It’s that kind of story, it’s fractally complex, in a way that I think is incredibly rewarding as a reader.

But also, I got to talk to Neil about it a lot, because he was creative consultant on all of those early Sandman spin off books. He was really generous with his time. I’d come up with an idea and I’d pitch it to him, and then we’d talk it through. He only ever said no to me twice, in the whole course of my role on this. One was a line of dialogue for Death, when Lucifer seems to be on the brink of death, and Death visits. He says to her, “You have no hold on me”, and she says, “I wouldn’t know where to put you anyway.” And Neil said, “She can’t say that, because she doesn’t have a realm.” All the other brothers and sisters of the Endless have a realm or domain that is theirs. Death doesn’t: she takes you from here to there, she takes you from this world to whatever your next stop is. She doesn’t have a place that’s uniquely hers. The other ‘no’ was about a character named Rose Walker in Sandman, who becomes pregnant. It’s very, very strongly suggested that the child is of the lineage of Endless; that something is happening which involves one of the Endless. I was going to have a Rose Walker story, and Neil said, “If I come back to Sandman, that’s the story that I will tell, so I’d rather you left her alone.” But apart from that, he let me run free, and was happy to bounce ideas around and be a sounding board.

This sounds amazing! And this was a collaboration with Peter Gross, with whom you wrote The Highest House – could you tell us about that one?

The Highest House is the story of a young boy named Moth. He lives in a fantasy world, Ossaniul, which is roughly mediaeval in terms of technology and infrastructure. It’s a world that has slavery as a tradition which is seldom questioned, and it’s quite easy to own another person. Parents own their children, and if they want to sell their children, that’s fine. A husband will own his wife, and can sell her on if he wants. If you take church charity, you become the property of the church, and the church can use your labour or sell it elsewhere.

Ossaniul also used to have a polytheistic religion, and many of the ruling families had made deals with supernatural beings – you could call them gods or you could call them demons, it’s debatable, but they were much more powerful than humans. These families have achieved their eminence in society with the help of these beings. And then Ossaniul is invaded by the Koviki, who are monotheists. They worship the Goddess, the Lady – she doesn’t have a name, she’s just the Goddess. And all of those old religions are now proscribed.

Moth’s mother sells him to a family that live in Highest House, a Koviki family who have taken over the family seat of an old Ossani family. Lord Demini Aldercrest is the head of the household. In the first few issues Moth doesn’t even meet any of the family, he just meets the steward, and he’s given a job as a roofer – when the new slaves come into the family, they take on a specialty. So he’s learning his trade, going around repairing thatch and shingles under the guidance of an older woman named Fless. But then he meets the demon-or-god, the creature that the former owners of the house made a contract with. It’s still alive, and it lives in one of the many basements of the house. It’s called Obsidian, and it’s trapped in a black stone. And it says to Moth, if you set me free, I will give you three wishes.

Moth says, “I’d like to learn to read, because knowledge is power. I’d like my sister’s eyes to be to be healed so that she can see again” – he has a younger sister called Jet who is going blind. “And I would like you to free the slaves. I’d like you to end the institution of slavery.” And Obsidian says, “I don’t get into politics. The other two wishes are fine.” But Moth says, “In that case the deal’s off. It’s that or nothing.” So Obsidian reluctantly says, “Okay, this is going to take some time. It’s going to be really complicated. But yeah, the two of us, we’re going to end slavery.” That’s the story.

What’s it like as a writer to share the story-telling so closely with an artist?

When we started Lucifer, we had a penciller and an inker: the penciller was Chris Weston, the inker was James Hodgkins. Both were riding high in their careers at the time, Chris Weston in particular was at the height of his game, and we were very lucky to have him. But then it turned out the two of them didn’t get on, they couldn’t find a modus vivendi. Chris was so unhappy with James’s inking that he took some pages back and inked them himself. So they both walked off the book after three issues, which ought to have been the end of the affair – losing your whole art team that early in the run, losing your visual identity, it’s catastrophic. So I sank into a deep depression.

And then I got a call from the editor, Shelley Roeberg as she was then – Shelley Bond now. And she said, “I’m going to approach Peter Gross. He’s just finished drawing The Books of Magic, so he’s free, and this feels like it might be in his wheelhouse.” So she called him up, and he said, “No, absolutely not. I’ve just spent the last six years, seven years, doing a fantasy comic; I want to do something different.” But she sent him a script, and he liked it. So he came on board cautiously – “I’ll see how this goes.” He came on with issue five. And since then, we have collaborated on something like 160, 170 issues of comics, over 2000 pages, and it is one of the most pleasurable and rewarding collaborations I’ve had.

Peter is amazing. The thing is, he’s not just a great artist, he’s a great visual storyteller: his art is always in the service of the story. There are some comic artists out there who do these gorgeous, flashy pages, but you have no idea what’s going on – there’s nothing to lead the eye. Peter’s pages are always kinetic, and they’re structured; they take you through the story in the right direction. He has amazing instincts as a storyteller. There’s a sequence in Lucifer, where we meet a guy who is ‘a good man in hell’ – he committed one unforgivable sin which he’s gone to hell for, and he accepts that it’s right. He killed a child in a fit of rage. And there’s a bit where we see that backstory, and I wrote it as three pages of normal art with about five or six panels per page. Peter said, “But he’s going to be thinking about this every single moment of every day. So I think we should tell it a million times; instead of just having five or six panels, we should have hundreds of panels just repeating and repeating and repeating, to give the sense of that obsession.” So that’s what he did – and it was beautiful, and much better than my original idea.

We ended up working together on the whole run of Lucifer, and on another long running series called The Unwritten; the DC Vertigo; a miniseries called The Dollhouse Family; and The Highest House… we just keep on keeping going, keep coming back and finding each other again.

You mentioned writing a script for Peter – can you talk me through the nuts and bolts of how a collaboration works?

It works very differently according to who you’re doing it with, and depending on how the editor does their job. Shelley was one of the best editors I’ve ever worked with, in that she would pick intelligent fights with the story: she would get what you were aiming for, and if she didn’t think you were getting there, she would throw it back to you to try again. But also, she was really good at keeping the rest of the team communicating, and making sure that we were all talking to each other, which is crucial in collaborative works.

When I’m writing for an artist I don’t know, I’ll write a very, very full script. Very specific, with instructions for page turns, instructions for art direction, instructions for the key panel on the page, and so on. And then I’ll relax gradually, as I get to know them. But there are only two artists with whom I’ve ever got to the point where the script becomes an invitation to negotiate, for a free back and forth – and Peter is one of them. When I send a script, he comes back to me with questions and suggestions. He would ask me where the story was going so that he could anticipate plot points. More than once, I would come up with an idea for a character and then he would draw the character, and the character’s voice would come from the drawing. I’d look at the character that he created and think, ‘Ok! Now I know who that is!’

There’s a horrible little imp named Gaudium who’s a fallen angel; and while most of the angels who fought with Lucifer were seraphs, big glorious six-winged beings with swords and armour and so on, Gaudium was a cherub. He’s a little fat dude. In his fallen version, he looks like a gargoyle who got a job as a New York cabbie, with a cigar sticking out of the corner of his mouth, and a little iron ring in his navel. The voice came very much from that sketch. Also, Gaudium was originally meant to be just a plot function, used to come in and tell a character something important, but he looks so great, we just kept on going back to him. He got three issues to himself over the course of the series.

For your next choice, we’re back to a single author-illustrator with Bone: The Great Cow Race by Jeff Smith.

This is a series that came out from 1991 to 2004. It’s a real oddity, and it’s a glorious story. There were nine volumes and then they did a one-volume compendium, which is well worth picking up.

It becomes a heroic fantasy in the style of Lord of the Rings: an epic struggle of good against evil, the evil being embodied in a mysterious figure, the Lord of the Locusts, and a monster named Kingdok, who is just this towering taloned fanged clawed hairy beastie. But in the middle of this there are these three characters who are like characters from a Disney cartoon – three little guys with bald heads and huge noses: Fone Bone, Phoney Bone and Smiley Bone. Smiley is incredibly innocent and not the sharpest tool in the box. Fone Bone is a good-hearted everyman. And Phoney is a huckster, a conman who is constantly getting into trouble and getting his two cousins into trouble. These three characters come into the middle of this story which gets darker and darker around them, and more and more serious, with the stakes getting higher and higher.

I love the whole thing, but I particularly love the early episodes where the comedic elements are to the fore. So in The Great Cow Race, there is this character they meet named Gran’ma Ben, who it turns out has a heroic destiny. But at this point, she’s just this grumpy old woman who is supernaturally strong. And every year in the village where she lives they have the Great Cow Race, where she races against cows, and she always wins. But this year, Phoney Bone decides he’s going to make money on the race, and starts a rumour that there’s a mystery cow – Gran’ma Ben’s getting old, the mystery cow is going to win this year. All the smart money’s on the mystery cow. And the mystery cow turns out to be just Smiley in a cow costume, and Phoney’s idea is to get everybody to bet on the mystery cow, and then Gran’ma still wins, so he gets to keep all of the stakes. But that’s not how it works out…

It’s all played out against the backdrop of this old evil coming back into the world. There are monsters in the woods, and the race is going to go through the woods. So quite dark stuff going on in the margins, but it’s really silly and funny… and Smith pulls it off! It could easily have just been a mess. But actually it’s really funny, and really exciting, and the art is just gorgeous. It’s very simple line art. As a kid Smith loved Carl Barks’ DuckTales, Donald and his three nephews. He said, “I would have loved to have read a DuckTales story that was 1100 pages long, and had a Lord of the Rings majesty about it.” So he decided to create one.

So do you get the impression he always knew it was going to become dark and epic?

I think so, yes, but it’s a huge surprise to the reader. You buy into this silly innocent fantasy, and then it modulates in a really interesting way.

It’s sometimes marketed as aimed at children, sometimes young adult… Who would you say is the audience?

The core audience is YA, but I think Smith said he never saw it in those terms. I think if very little kids read it, there’s some messed up stuff later on that could be disturbing. But then you can say the same for things like Harry Potter, and kids are emotionally robust. So I would not quarrel with it being read by children, provided the parents are looking over their shoulder and mediating a bit.

Let’s talk about your next choice, the second in the Beanworld series by Larry Marder – Beanworld: A Gift Comes.

Larry Marder is such an intriguing and extraordinary figure. He started off self-publishing this, and then at some point – I think in the late 1980s – he sold it to an independent publisher called Eclipse Comics, and Eclipse put out 21 issues. And that’s all there ever were. I think he later did some short stories, but the original run of the comic was just 21 issues.

As with Bone, the Beanworld books have a very engaging and simple art style. The core story is about a tiny world. Most issues start with a little map of the world, and it’s just an island, with this strange abstract ocean around it: that is the entirety of the Beanworld. On one side there’s the Legendary Edge, and on the other side is the Proverbial Sandy Beach. And it’s inhabited by little beans with arms and legs.

They eat something called chow, and in order to obtain it they have to dive off the Legendary Edge into the Four Realities. They go down to a place where there are huge creatures called the Hoi-Polloi, who hold chow, so the beans have to fight the Hoi-Polloi, grab the chow and bring it back. They don’t eat it, they just immerse their bodies in it, and they absorb all they need to live. And then the other side of that transaction is that there’s a tree at the centre of the island, and every so often, the fruit of the tree falls down – that’s called a sprout-butt – and they take that down and give it to the Hoi-Polloi. The Hoi-Polloi make chow out of the sprout-butt. The sprout-butt itself is sentient, and consents to being turned into chow.

It’s very odd! But from this really simple schema with very few elements, Larry Marder creates a little tiny epic, which is just wonderful to read. The beans have a hero called Mr. Spook, who has a weapon – it’s a trident, but they call it Mr Spook’s fork. The main character is called Beanish, and he becomes a kind of shaman to the beans. He discovers that every day he can ascend into another reality where he meets this lady named Dreamish, who is like the goddess of the sun. Or she’s just a sun with a face… she refuses to explain what she is. And he starts to learn that he can control time to spend more time with her, he can extend the moment of noon as long as he wants to.

In Volume Two, A Gift Comes, a couple of really game-changing things happen. The first thing is that Mr Spook loses his fork: it gets stolen from him by these strange little creatures called the Goofy Service Jerks. And the other thing is that a gift come. A messenger comes and tells the beans that there will be a gift, and they don’t know what the gift is; and most of the book is them preparing for it. And then the revelation of the gift…

Listening to you explain these last two, I’m very struck by how ‘out there’ these are – I’m struggling to imagine them in in any other form. It’s the sort of under-explained magical worlds, almost fairy tale-like, that are maybe harder to do in prose – to present all this as a fait accompli…

Fairy tale or folkloric. One of the inspirations for the Beanworld was Native American mythology. Marder originally had an entire myth cycle in mind.

He was doing this from the mid-1980s to 1993. In 1993, he was given a job as executive director at Image Comics, and he just stopped writing and drawing. He worked for Image for six or seven years, increasingly involved not even with their comics but with their toy division; and then he got a job working for the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund, he was in charge of that for several years. And his creative output just stopped, which was anguish and agony for me and many of his readers. And he seemed to be very fulfilled by those administrative jobs! He never talked about them as any kind of sacrifice. He does now talk about coming back to the Beanworld, but he’s quite cautious about it. He’s making no promises. As I said, he had an entire myth cycle in mind; he said this is spring, and he was going to do all four seasons. But one of the inspirations for the stories was his relationship with his wife, and she’s dead now. The character of Dreamish, the sun with the face, was very much based on his wife. And in his mind when she spoke, she spoke with his wife’s voice. He’s not sure that he can recreate her now.

All these entirely non-human characters feel like something that graphic novels can uniquely pull off. I can’t imagine trying to persuade a reader to explore what it would be like inside the head of a bean, through prose. But I can absolutely imagine being instantly drawn to an anthropomorphised bean in visual form…

Yes, absolutely! Marder is doing something that’s unique to comics, I think. It’s like how Snoopy’s doghouse doesn’t work in three dimensions, in the Peanuts cartoon – he lies on the roof, and it’s a pitched roof, so he’s lying on a point, right? You only ever see it from the side. Schulz said himself that if people try to visualise it in three dimensions, it falls apart instantly. The Beanworld is the same: it’s a two-dimensional projection. It’s a plane. It’s a world that has no depth, it’s like an ant farm. You only ever see it sideways on.

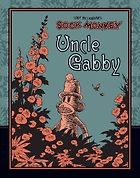

Let’s talk about your last choice, which features another non-human hero – Sock Monkey: Uncle Gabby by Tony Millionaire.

My relationship with Tony Millionaire’s work is ambivalent. He’s an astonishing graphic artist. I’ve heard it said that he started drawing on a napkin in his local bar, and the guy behind the bar said, ‘I’ll give you a free beer for every cartoon that you do.’ So for some years, he drew for beer. And then he created a strip for The Village Voice called Maakies. The characters are the same characters, really, as in Uncle Gabby: a monkey toy made out of a stuffed sock, and a crow. But in Maakies they’re usually crew on a sailing ship, and they are alcoholics who are always on the brink of existential despair. Maakies is a really, really dark strip about alcoholism, full of violence, full of sadness and guilt and anguish. And it’s not funny. I mean, it’s intriguing; but there’s no lightness there. And then weirdly, Millionaire does the Sock Monkey stories alongside Maakies, with different iterations of the same characters.

In this one, the sock monkey is called Uncle Gabby. I love this book because it’s a meditation on memory, on our relationship with our past. Uncle Gabby is plagued by memories of things that couldn’t possibly have happened. He remembers events that are incompatible with the life that he’s living. He decides that he has to resolve that anomaly: he has to find out which of his pasts is true, the one he remembers or the one that ought logically to be true. It’s mostly black and white line art, switching to colour at the end, for a triumphant, breathtaking ending. It’s got a lot of emotional heft to it.

As with Beanworld and Bone, the art is simple. Millionaire was very influenced by Johnny Gruelle, who created Raggedy Ann and Raggedy Andy. You can see that especially in the characters who are like toys animated to life. There was a Sock Monkey story That Darn Yarn, which won the Eisner Award for the best humour comic. And I remember reading it and thinking, “But it’s not funny! You’re not meant to laugh at this!” There’s a lot of melancholy, a lot of quiet sad reflectiveness in the stories. But they are incredibly beautiful, and I think he’s a unique talent.

Thank you so much for talking fantasy graphic novels with me today. Before we go – you mentioned that your contemporary list would look very different

.

Off the top of your head, do you know what you’d include?

My contemporary list would have a lot of non-English stuff. There are so many amazing fantasy comics coming out on the continent at the moment… From Italy, Lorenzo Mattotti’s Garlandia is utterly amazing. There’s a guy named Burniat, who’s just done a book called Furieuse about King Arthur’s daughter. King Arthur is old and not what he used to be; he’s become a grumpy old tyrant. And he’s going to marry his daughter off to a nobleman, and she doesn’t want any part of it. One night, she’s lying in her bed and Excalibur comes along and says, ‘Look, you’re disappointed in what your dad is now. I’m disappointed in what he is too. Why don’t we just go on the road?’ So she just takes off with this magic sword… It’s a terrific exploration of gender roles and class divisions in a mediaeval society. It’s absolutely wonderful.

Joann Sfarr’s The Rabbi’s Cat is amazing. There’s a book by a guy named Tim Probert, Lightfall, which is a YA book about a little girl who meets a monster and they have to try and save the world; the light is going out of their world, and they have to find a way to bring it back. There’s an Image book called Head Lopper, which is about a hero who kills monsters for a living, usually by chopping their heads off…

If you’re browsing a bookshop, it does feel like we’re in a golden age for these stories. But I don’t know if there’s actually more work, or it’s just better stocked in bookshops.

I think there is more work. Comics have become culturally mainstream, which didn’t happen that recently – it happened because of books like Sandman. There was a moment when that secondary market opened up, when comics become routinely collected into trade paperbacks. That changes everything. I think it has led to an enormous increase in output. And of course there’s Sturgeon’s Law, that ninety percent of everything is garbage, so there’s a lot of stuff out there that’s not great; but it does feel like we’re living through a golden age. Especially if you go to France! If you go to any bookshop in France and go to the bandes dessinées section, you see this extraordinary plethora of formats and styles and genres that you would never encounter in English language books. Much it now is getting reprinted – Fantagraphics in America does English language reprints of a lot of continental books.

Interview by Sylvia Bishop

June 21, 2024. Updated: August 7, 2024

Five Books aims to keep its book recommendations and interviews up to date. If you are the interviewee and would like to update your choice of books (or even just what you say about them) please email us at [email protected]