What is it for someone to die? Is there an accepted medical or legal definition?

There are several. We can talk, for example, about brain death. In terms of brain death, it’s a clinical assessment of whether there’s any activity in the brainstem of the body. It’s a fairly definitive indication that there is no life if no information is travelling to and from the brain, because the brain is fundamentally the major controller of the entire body. But in the normal course of events, we tend not to talk about brainstem death. We tend to talk in terms of general organ shutdown: when the heart stops beating, when respiration stops.

At that point, if we assume that we’re not going to put someone on an artificial respirator or something of that nature, then we say that death has occurred if the individual is not naturally, by themselves, breathing or the heart is not beating. We can help them breathe but we can’t do much about the heart beating. Sometimes it’s a cardiac death and sometimes it’s a brainstem death. But, technically, death is the point when you can no longer restart a whole body life function.

As both a distinguished forensic anthropologist and human anatomist, can you outline what these fields involve?

Human anatomy is the study of the gross aspects of the human body. What we mean by ‘gross’ is not what is viewed at the microscopic level, although that is a part of anatomy, but what you can see when you open up the human body. In dissection, we’ll start dissecting a body from the top of the head, and dissect all the way down to the little toe. I can remember thinking as a student, ‘Why on earth do we need a whole year to be able to do that? Surely we can do it in an afternoon’.

But once underneath the skin, you start to get an appreciation of just how complicated the human body is in terms of the number of nerves and the number of arteries and veins and all of the different structures. You realise that, actually, to study it requires an incredible amount of time and attention. When you’re in the dissecting room, you are in the constant company of death and, through death, you are learning. It’s a really interesting relationship that the anatomist develops with the dead body.

“When you’re in the dissecting room, you are in the constant company of death and, through death, you are learning.”

Forensic anthropology is more about determining who that person was when they were alive. It’s about determining what indicators and pieces of evidence you can recover from these mortal remains: whether they’re a skeleton or badly decomposed, or (if they’re relatively recently deceased) perhaps in several pieces as the result of an explosion or dismemberment. Given what’s in front of you, what can you tell about that human being when they were alive? That’s forensic anthropology.

Sometimes DNA helps us enormously—of course it does—but when you don’t have DNA to compare with, then we have to go down the old traditional route of what the human body tells us. And to understand what the human body can tell us, you should be an anatomist first of all. The two are very closely linked. One is the training ground for the specialism of the other.

With popular shows like CSI or Silent Witness, what are the most common myths about these fields that make you want to scream?

I silently screamed when you said the name of both shows. In some ways, you’ve got to bear in mind that these are about entertainment. They are not educational programmes and they’re not there to be realistic; they’re there to tell a story and hook people. Provided you can view it in that way, it’s tolerable. The problem is that young and impressionable people—usually young students in school—view these programmes and think, ‘Gosh, that’s something I really want to do’. But they aren’t getting a realistic expectation of what the job actually entails. There’s a risk that they misrepresent the entirety of the field of forensic science and investigation because they’re driven from an entertainment perspective.

But the real problem also arises in the courtroom. In the courtroom, the jury, the triers of fact—the most important people in the room—come into court feeling that they are forensically aware because they’ve watched CSI. And, of course, they are not! They get very cross sometimes. They think because on CSI you can get a DNA sample analysed and the crime solved in forty minutes, how can it take you six months to get a sample? Does that mean that you’re not very good? So, these programmes may inadvertently raise unrealistic expectations due to the lack of understanding that they’re entertainment, not education.

Before we look at your choices, I want to talk about your remarkable book, All That Remains. You have these reflections in parallel about proximity to death—both in a forensic sense throughout your distinguished career, but also in your personal life as a niece and as a daughter. And in wonderful moments, they intersect. I’m thinking in particular of your uncle Willie. You check over his body in the chapel of rest to make sure that his corneas haven’t been stolen, and then you wind up his watch to make sure it’s working . . .

Oh no! [Laughs]. There are times when, as an older person, you look back at what you did when younger and think, ‘Oh really! I should probably have been certified at that point.’ But it’s funny—we tend to talk about professional and private life as though they’re separate things, but they’re not. They’re so connected and intertwined in the person. All of us have multiple personalities that we juggle on a daily basis—whether it’s as a professional or meeting a stranger or doing some involuntary work. All of these personalities are there within you and you manage around them on a daily basis.

But when placed into a situation in extremis—a situation where it’s difficult to decide whether to act as a family member or a professional—we tend to do things that are slightly out of character. Until writing the book, I’d never actually told anybody about what I’d done, because by the end I realised that to anybody looking in from the outside, I’d probably behaved in a slightly lunatic fashion.

It was this clash of identity, of knowing. Who am I in that room? My father sent me in as a professional, but he was still my uncle Willie. Often, that kind of bizarre behaviour occurs when in the overlap and intersection between different parts of our lives. That’s when we do things that are totally unexpected. It’s a wonderful learning experience within us that says when we’re taken out of our comfort zones, we actually learn most about ourselves.

When it came to my father or mother dying, I already had that ridiculous experience— God bless him!—with my darling uncle Willie, so I didn’t feel the need to repeat it with either of them. I’d grown up a little bit since then. Uncle Willie was the first family member I’d ever seen dead. I put it down to youthful exuberance, as well.

It’s a very warm book with poignant moments that made me laugh and, I admit, tear up in places. It presents fascinating science in a very accessible way: you talk, for example, about the four different cellular types that are never replaced over the course of a life. And it’s gorgeously written. There’s a vivid, moving discussion of how you’d like to die in the Epilogue.

Thank you. I’m not very good at this. I’m a classic Presbyterian Scot—I take criticism much better than I take praise!

The trouble is that what we want is rarely what we get. When my children were growing up, they’d say ‘I want . . .’ and I’d say to them ‘“I want” doesn’t get. “Please may I have” has a much better chance’. We might all decide what we want in death but, when the moment comes, might not get it. Or we might get to a point of realising that what we thought we wanted is not actually what we really want now, when it faces us very squarely and firmly. I can have these imaginings that this is what I’d really like—and it is—but facing it on the day may be entirely different.

Your first book is Unnatural Causes by Richard Shepherd, who is one of the leading forensic pathologists in the UK. Can you tell me about this book?

First of all, I’d like to tell you about Richard Shepherd, or ‘Dick’. I know him very well; he was the first pathologist that I worked with in London. We’ve shared 30 years of a career together, which is a delight because he’s brilliant company. I’ve always respected his expertise as much as I cherished his friendship, but he surprised me. I’d never known that he was going through the personal difficulties conveyed in this book, in relation to coping with the cumulative trauma that he had experienced over his professional life.

At one point, he said to me: ‘It isn’t natural for anybody to do 20,000 post-mortems in their lifetime’. And he’s absolutely right—it isn’t natural. These are unnatural causes being looked at in unnatural circumstances by somebody who is trying to be very natural in their profession. You can see the tension and the conflict in this.

He’s very open in his dialogue. In fact, I wrote the little puff on the front of the book which describes it as “heart-wrenchingly honest”. He talks about how, for example, he’d bring his work home, sit down at the family dinner table and look to see, while carving the roast joint in front of him, what sort of a wound different knives left. Looking back, he could see these crossovers between his personal and professional life. Though they seemed perfectly normal to him at the time, when looked at cumulatively, he could see how others might perceive abnormalities.

“He said to me at one point ‘it isn’t natural for anybody to do 20,000 post-mortems in their lifetime’. And he’s absolutely right. It isn’t natural. ”

He could see how crucial the decision was: do I go out to the police call and leave my family behind, or do I stay at home? There’s a dreadful adrenaline rush accompanying any police call that asks, ‘Can you help us? We’ve got an incident and we need you here’. It’s human nature: wanting to be needed, knowing that you’ve got a skill you can bring to a problem. But in prioritising that, what you’re doing is de-prioritising the most important things any human being can have in life—the love and care of those around you. Your job will never love you back in your old age; only your family will do that. It took Dick a long time to reach that realisation.

He talks very candidly about his descent into post-traumatic stress and how, for him, its trigger was something so simple: it was just somebody dropping ice cubes into a glass. Since the Bali bombings, which he’d been around for, he had flashbacks. Within our field, we try to be these terribly brave warriors who say, ‘No, this doesn’t affect us. I’m perfectly okay with the horrors that we see.’ I once heard somebody liken us to modern day sin-eaters: we are the people who consume the sins of the rest of the world, so that other people don’t have to deal with them. But that has its toll.

“He talks very candidly about his descent into post-traumatic stress and how the trigger for him was something that was so simple.”

It was a huge surprise for me that somebody like Dick—who I never anticipated would have experienced that level of trauma and stress—could be so open about it. It is a real beacon to the professionals in the world to say: you are not immune. We are all potentially open to this form of self-destruction, and need to be ever-wary and conscious of it. Dick’s book was a real warning and a real eye-opener to the professionals, but it also gave the public a realistic representation of how our job is not normal.

While going into court looks like this wonderful battle, it’s sometimes the professionals in there who are the punching bag. So many of our practitioners leave the profession because (a) the courtroom is so adversarial for us that they don’t want to put themselves through it; and (b) they’ve just got to a point of enough where they can’t consume any more sins of the world. It’s a beautiful book but, my goodness, it is heart-aching.

Get the weekly Five Books newsletter

There is the idea that working so close to death requires a level of desensitisation and, perhaps, emotional repression. Can anybody fully desensitise to death in an emotionally healthy way? And is it necessary to do so?

That’s a really good question. I don’t think that there is an answer to it because it is so personal. Some people cope with it in entirely differently ways. Desensitisation came for me as a child; I was responsible for gutting and skinning rabbits because my mother was too squeamish to do it. Throughout my time at school I worked in a butcher’s shop, so I was always up to my elbows in blood and bones and viscera. Later, in the anatomy department, I learnt how to dissect a human and then, in the mortuary, I learnt how to investigate the body for evidence. So, I had these learning steps into that field.

For a student, that’s often quite difficult because they haven’t experienced death until they’ve stepped into a dissecting room. With practitioners who aren’t anatomists, often the first time they’re confronted with it is in a mortuary. The more you can lead yourself into it, the more you have two opportunities: either to get yourself out because you realise it’s not for you; or to acclimatise yourself to what it is you’re seeing and what you’re doing.

How you then cope with this on the ground is entirely individual. Some people shut it away and pretend it didn’t happen. Others face it, identify it, suppress it, and get on with the job that you need to do. For me, it’s about thinking that I have a clinical box inside my head. When I go into a job, I walk into that space, physically in my own mind, and shut the door behind me. And I leave my own world behind me. I deal with what I have to do inside that clinical box, and when I’m finished, I come out and close the door.

The demons of my professional world are inside the box, and the demons of my personal world are outside the box. What I’m very careful about is who opens the door of the box—who do I let in, and who do I not?—because I don’t want my two worlds to bleed into each other. But Dick’s book taught me that, with the best will in the world, sometimes you risk not shutting the door properly. You have to be prepared for the aftermath of what is, fundamentally, Pandora’s box.

“When I go into a job, I walk into that space, physically in my own mind, and shut the door behind me. And I leave my own world behind me.”

It’s a beautifully written book. The shock for me in it was more personal—in not knowing that this man, who I consider to be such a good friend of mine, had been going through this. If I had, I’d have reached out to him. I’ve metaphorically slapped him about the face a few times since we’ve met: Why didn’t I know? Why didn’t you tell me? And he said that he couldn’t; he had to get through it on his own. That, I think, is a real lesson.

If you love somebody enough, you have to let them do some things on their own. But other times, I think that if I’d maybe asked certain questions of him earlier, I could have been there, and helped. If you look beyond the fact that this is a book about forensic pathology, you see there’s a huge lesson for everybody in its humanity.

Your second book is Death, Dissection and the Destitute: The Politics of the Corpse in Pre-Victorian Britain by Ruth Richardson. This is a legal, social, and medical history of the 1832 Anatomy Act. Can you tell me about this one?

Ruth Richardson is one of the most methodical historians I’ve ever come across. This book is not a toe-tapper for a Sunday afternoon, or for lounging on a beach somewhere. She really looked at the entire world associated with anatomy—in which I’m firmly embedded—and how it reflected and impacted upon society at this particular historical moment.

Anatomy has always had a relationship with the dead; that’s how we learn. But in the early days of anatomy, most dissections were actually done on animals. The shift to the dissection of humans made for quite an important political, societal, and religious stance. The period Richardson examines was a time not only of political and religious upheaval, but also of scientific enlightenment. Again, there’s an inherent tension: you have these educated, academic people desperate to learn because they see a potential benefit. They know, intuitively, that to better understand the human body is to be able to save lives. So there’s a drive, from an educational and humanitarian perspective—but where do you get the bodies from?

Up until that point, the only way that you could legally acquire human bodies for dissection was if they were convicted murderers, cut down from the gallows. Hanging people fell out of favour for a bit; we were much more likely to deport them to colonies. By sending them away, we were getting rid of people we didn’t really want in society while also ensuring they were pioneering the British Empire. Problem was, there now weren’t enough bodies.

“You have these educated academic people who are desperate to learn because they can see there’s a benefit in this: if I understand the human body better then maybe we’ll be able to save lives. But where do you get the bodies from?”

How do we feed a machine of science and education hungry to move forward when we don’t have the means to learn? Medical books were very expensive and still quite rare. Animal corpses weren’t telling us about the human. With the Anatomy Act of 1832, we could acquire bodies from prisons, poorhouses, and mental institutes. Before, the cadaver came from the criminally convicted; now, it came from the poor. Because that essentially equated the poor with felons, there was a huge societal upheaval about how this was not right. And so people started to protect dead bodies.

But nature abhors a vacuum—the minute there’s a commodity of a sellable nature, I’m afraid, human villains will always find a way to exploit it. So, we get into the whole area of acquiring bodies illegally, which captures the human imagination and reverberates through history to this day, whether it’s body snatchers (who were actually removing corpses and stealing them from graveyards) or the extremes likes of Burke and Hare, who decided they’d remove the middleman and not wait for people to die—they’d murder them to provide for the anatomy houses.

Richardson is able to condense this huge tapestry of perspectives—of education, government and politics, societal upheaval and tensions, religion and empire—into a book. It is the most incredibly thought-provoking dialogue of the history of anatomy at a time of turmoil.

And we learnt enormously from it. We learn and stand on the shoulders of real giants—and one of the real giants of the time was Jeremy Bentham. Bentham advocated that we need to get away from looking at acquiring corpses for study as inherently bad; he thought we needed to change the culture and the perception. He was actually one of the first people who voluntarily chose to donate his body to anatomy on his death. Of course, all anatomy bequeathal is now done on that basis: live individuals make the decision to donate their body to the science of anatomy.

In the midst of this, Bentham was a real pioneer who found a way forward, even though it didn’t actually take off as well as it should have done at the time. The real change in anatomy bequeathal came around the Second World War. Tapping into the the country’s patriotism, we were able to say: we need to train our surgeons, we need to train our doctors, because we need to be able to save the lives of our young men who are out on the battlefield. But Jeremy Bentham, right in the middle of this period that Richardson portrays so beautifully, is the one that lit the lantern for the way forward.

What’s the present legal situation concerning unclaimed corpses?

Where we have unidentified remains, then they must be buried as unidentified remains. They are not passed to anatomy departments. Anatomy departments in the UK can only accept bodies through a bequeathal process. You cannot bequeath your granny; your granny has to bequeath herself. That was a change that came relatively recently, since the new millennium. Prior to that, a family could bequeath granny’s remains without her permission. Now, you can’t do that. This isn’t true in other parts of the world, though. In parts of America, the John Doe or Jane Doe can be donated into the body programme. We can’t do that in the United Kingdom.

And you’re aiming to bequeath your own body, is that right?

Absolutely! Somebody needs to do something with it, at the end of the day. I view it as a terrible waste to be worm food, or go up in smoke and increase pollution in the world. We really don’t need that.

I would like to choose my own death. We all would. I don’t want it to be a protracted affair; I don’t want it to be medicalised; I don’t want it to be undignified. I want to be in a position of sound mind where my ducks are all in a row and my family all know that this is my way, and I want to decide when I’m ready. I would love to be in a position to be able to take a pill that would allow me to do that, but at the moment in this country that isn’t possible. I accept it’s not for everybody, and I accept that there absolutely have to be legal constraints to ensure the system isn’t abused. But I love to think that we could reach a point of sufficient maturity as a society that we can give people the right to choose.

When I die, I want my body to be donated to Dundee University, home of the Thiel embalming process. I really want to be Thiel-embalmed, not with formalin—formalin is really horrible stuff. When they’ve finished dissecting me, I’d like them to collect my bones, boil them down to get rid of the fat, and reconstruct my skeleton. I’ll be a standing articulated skeleton in the dissecting room. That way, I can carry on teaching for the rest of my death.

It’s strangely beautiful, isn’t it?

It’s gorgeous! It’s perfectly normal: an anatomist who wants to teach. Quite often you find that when an anatomist retires, they go back and teach part-time. Anatomy is one of the greenest departments in a university because it recycles its staff. They come in, teach, retire, come back to teach part-time, and when they die, come back and teach yet again—albeit silently.

“When they’ve finished dissecting me, I’d like them to collect my bones and reconstruct my skeleton. I’ll be a standing articulated skeleton in the dissecting room. That way, I can carry on teaching for the rest of my death.”

If you genuinely believe in the principles of what anatomy teaching is about, then, in our slightly unusual minds, it seems perfectly natural.

Five Books interviews are expensive to produce. If you're enjoying this interview, please support us by donating a small amount.

We’ve been talking about the use of human remains for medical education. But I’m curious to ask your position on the use of human remains in the art or entertainment industry. For example, David Tennant used a real human skull when playing Hamlet for the RSC. And we also have Gunther von Hagens’ BODY WORLDS exhibition in London.

It’s a really difficult one. Gunther von Hagens is (was?) a marvellous anatomist. His skill and his techniques are phenomenal. Am I comfortable with human bodies being displayed? Not really. But people have allegedly bequeathed their remains for that purpose. If people choose to do that, that’s entirely up to them. If people choose to view them, that’s entirely up to them. My choice would be not to go and view. I don’t feel that human anatomy is there for entertainment. I feel it’s there for education. I find it a slightly distasteful barrier between one and the other.

I can remember in the early stages of the programmes that Gunther von Hagens did on television—he brought in a wooden box on a forklift truck and inside the wooden crate was a frozen human body. And then, on set, with a bandsaw, he sawed the human body down the middle. My question is: why do people need to see that? What do people learn from that? I don’t actually think they learn anything. And if they don’t learn anything then what’s it about? It’s about titivation and it’s about entertainment. That causes me a problem.

If, however, the programme is saying: ‘look, here is the heart; here is the anterior interventricular artery—this anterior descending branch is the one most likely to block; how it blocks is because of arterial sclerosis and we get that because of cholesterol in food’, then I can see how you’re using the anatomy dissection to be able to inform the public. And that is about education. So, I’m not against the public viewing anatomy. I’m uncomfortable with what is the ultimate intention.

Your next two choices are novels. Let’s first discuss The Trick to Time by Kit de Waal.

This is not normally the kind of book that I would read. But since I’ve written a popular book, it’s amazing how many other books get sent to you to read that you wouldn’t normally buy. The write-up on this book wouldn’t have directly appealed to me. So, there was a huge learning process in there which says to me don’t necessarily believe what’s written on the dust-jacket, because when you get into the story, it is really beautiful.

The story is about dealing with death. I’ll only take it so far because I don’t want to spoil it for anybody. It talks about a woman who has clearly had difficulties in her life. As the book progresses, flashbacks show you how her life has developed. There’s the relationship she had with a man—she absolutely adored him—who left her, and her losing her child. In losing her child, she had to find her way of coping with the death. And she found that she was not alone in the world as a woman who had lost their child.

People would come to her to talk about the loss of their child and how they coped with it. She had a relationship with a carpenter. After meeting with another woman who’d lost her child to talk about the child (particularly the weight of the child), she would then go to the carpenter and ask him for a piece of wood that would be carved into a beautiful work of art, that was exactly the same weight of the baby. And that piece of sculpted wood would be handed back in a shawl to the grieving mother, so she could hold something that was the same physical weight as the baby she had lost.

I met Kit on a radio show and asked her where this had come from. In her professional life, she’d been involved with a lot of work associated with women and grief and the sociological counselling of women in grief. She says that she created it in her imagination—it doesn’t exist—but it’s so believable that I genuinely feel that women who read her book could understand why they would want something of that nature. It is that crossover, again, between what is a professional world—a creative world, because this is a novel and this is fiction—where it is sufficiently believable that there’s a bridge occurring between the two, that there’s a mechanism suddenly created that might help some of these women in that grieving process.

So, I thought it was really beautiful. It’s a subject that we don’t normally discuss; when somebody loses a baby, as the chaplain at my university says, we tend to use soft words spoken at a safe distance. And when you’re in grief, that’s not what you need. You don’t want the placatory ‘I’m sorry for your loss’, because that doesn’t mean anything. You want to have that really difficult conversation with somebody that says, ‘This is how I really feel—how do I get out of it and how can I help myself?’ And to me, the totally out-of-left-field experience produced in The Trick to Time was really innovative. I wonder now if any woman has followed up on that, having read it.

The book explores the delayed experience of processing grief. As you mentioned, these were things that people weren’t really talking about. It seems people weren’t allowed to publicly grieve or have that communal aspect. Do you think that’s an important part of working through bereavement?

I think, as we discussed before, it’s so very personal. Some people need time to revisit the grief on different levels. Some people want to try and deal with it right away. There isn’t a right and there isn’t a wrong. There is a philosophy around grief which says that you don’t get over the loss of a person who mattered to you; what you do is accommodate around it. Your life grows around it and buries it in some sort of way, but it doesn’t go away. It’s still there. Every now and then, a little piece of it comes up to the surface.

“There is a philosophy around grief which says that you don’t get over the loss of a person who mattered to you; what you do is accommodate around it.”

It was the most awful thing to lose my father, but it was at a time where it was right for his age. It was a grieving process, and it was an immediate one. But, gosh! The number of times that man comes into my life! Even today, I open my mouth and hear my father fall out. My children open their mouths and I hear my father’s words come out. And although they make us laugh, there’s still also that little pang of loss. We don’t ever lose the grief, we just work around it. The more tools and mechanisms that we have, I think, the greater the opportunity we have to find our own personal way through it.

Let’s look at The Love Song of Miss Queenie Hennessy by Rachel Joyce.

This was, again, another book that I wouldn’t normally have read. It came out of the same publishing house as mine; I’d been chatting with the author and went away and ordered it. She wrote another book called The Unlikely Pilgrimage of Harold Fry which is about this man’s journey to meet Queenie Hennessy. Queenie is somebody that he met whilst he was at work. Harold was married but she was not—she was really quite besotted with him and he didn’t notice. But the book The Love Song of Miss Queenie Hennessy is from her perspective. So, there’s a book from his perspective and there’s a book from her perspective.

Her perspective is that she’s terminal; she’s in a care home—a hospice—in the borders of Scotland. He’s down in the far south of England. His pilgrimage is that he’s going to walk to her. She’d written a letter to tell him that she’s terminally ill, and, for whatever reason, he’d decided that he was going to walk from the south coast of England all the way to the Scottish borders and he has told her that she is to wait for him to arrive. His book talks about the pilgrimage, and hers talks about how she knows that he’s heading towards her. She’s trying to stay alive for the whole time, waiting for Harold to arrive. He’s not sure why he’s doing it, but she knows that she wants him to do it because she’s still very much in love with him.

It’s this concept of knowing that death is coming but waiting for something else to happen—and being able to almost postpone your own death whilst waiting for an event to occur. Again, I’m not going to spoil the book for anybody because the last part is really important. She is conveying to the nuns in the hospice her story of her relationship with Harold, what it is about him that’s important, and how she’s lived her life without him, yet always with him. And, finally, she’s coming towards the end of her life, she feels he’s finally coming just for her.

“It’s this concept of knowing that death is coming but waiting for something else to happen—and being able to almost postpone your own death”

I’ve seen this in my own family and others also say that it exists. When you know you’re dying—and we all know that’s going to come—if there’s a really important event that you’re waiting for, whether it’s a wedding or a birth or Christmas, it’s amazing how many people make that date and then die shortly afterwards. It’s almost as if death gives us a little bit of leeway, provided we have a sufficiently strong case to make. It’s a sad story but it’s a hugely uplifting story.

And the novel reflects this. Some people think it’s an urban myth, but I don’t think so. I think the human spirit is incredibly strong; we can overcome the vagaries of our health and our death if our spirit and will are strong enough to get there. Obviously, sometimes it doesn’t happen that way, but there are so many instances I’ve heard of where people have got to that milestone and almost stopped directly thereafter and let death come.

I really like this juxtaposition of a literal pilgrimage that Harold’s undertaking, compared with Queenie reminiscing in her hospice bed. This book is an odyssey of interiority, if you like.

It is. When I spoke to Rachel about it she said she was only ever intending to write Harold’s perspective, but she said everyone kept asking, ‘But what was Queenie thinking? What was her side of the story?’ So, Harold’s book almost forced her into thinking about it from Queenie’s perspective. I think it’s a lovely indication that the strength of the story was enough to transcend one book, requiring someone else’s perspective.

There’s a bittersweet sense of friendship that arises in the hospice—which is an environment by its very nature where one cannot escape the impermanence of the companionship.

There are wild and wacky characters in the hospice who all know they’re dying. In that regard, for some people, knowing that you’re going to die is actually a release. You can say the things you want to say, and you can perhaps do the things you want to do. You have a different perspective on what’s important within the time that you’ve got left. You can be happy if you want; you can be sad if you want; you can be on your own if you want. There’s almost a strength that is given, which asks: for these final hours, days, weeks, months, how do you want this to go?

“In that regard, for some people, knowing that you’re going to die is actually a release. You can say the things you want to say, and you can perhaps do the things you want to do.”

Often, we feel there’s a way in which we should behave. What this hospice gives the patients is the ability to behave as they want, fundamentally, and to say what they want. There are people they get to like and there are people they don’t, but this is just accepted. There are things they want to eat and don’t. There are things they want to hear and don’t. Around what’s happening to Queenie, there’s a background—almost a fog—of the complexities of the others who are going through their own stories. There’s a total acceptance amongst them all that they’re going to behave individually the way they want to up until the very last moment.

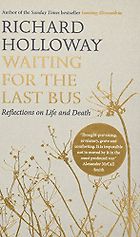

Your last choice is Waiting for the Last Bus by Richard Holloway.

I have an absolute and utter crush on Richard Holloway and he knows it. I call him my ‘delicious bishop’. He is one of the most beautiful people that I’ve ever met, inside and out. His mind is just the kindest and sharpest. He is a real academic who questions and doesn’t accept. His time as the Bishop of Edinburgh was really interesting because he was a challenge for some people but, for me, he is just an incredible one-in-a-lifetime person.

At the recent Saltire Literary Awards, Waiting for the Last Bus was up. I sat in the audience thinking, ‘Please, please, let it be Richard’. And it wasn’t. It was mine. I felt so disappointed that my book was chosen over Waiting for the Last Bus. That sounds terribly sycophantic, but it’s not. When I stood up to give the acceptance speech, I said we need to remember that books affect different people in different ways. I’ve been so touched by so many people who have said such nice things about my own book, but I have to say the book that affected me most in this year was his.

Richard is in his eighties and knows that he is waiting for his last bus. In a way that only he can do, he is mixing that dialogue of what he thinks and rationalises in his own mind with what he reads and has learnt about in his academic, prosaic world back into his beliefs and his religion. They aren’t necessarily the beliefs and religion of a specific church, but of humanity in general. It is a small book that is enormous in terms of its reach. It makes you think at levels you didn’t think you had the ability to have some opinion about. It also opens up doors that you didn’t even know were there. As only Richard can, he gets you on the very last paragraph or so of his final windup when he says ‘I’ve just lost my last dog’. It’s about saying he now knows he is ticking off on his list the things that he knows he will never do again.

“It is a small book that is enormous in terms of its reach. It makes you think at levels you didn’t think you had the ability to have some opinion about.”

To have somebody who is such an inspiration in a mode of acceptance, knowing what he now will and won’t do, is such a calming influence and an example to us all to be able to say, ‘Let me get to his age and give me the wisdom to be able to know what’s important in my life and what isn’t. And grant me the time, the peace, and the silence to just think before I die’. We spend so much time doing and don’t spend enough time thinking. Richard Holloway reminds us how important thinking is to humanity.

And it’s worth saying that its subtitle is “Reflections on Life and Death”. It’s not an overly morbid book.

Absolutely, I don’t think it’s morbid at all. It’s about Richard saying here are all the things that I’ve learnt, and I’ve done. He’s processing them and analysing them and deciding what he thinks is actually important. I think it is very life-affirming. But he’s doing in it in the mirror reflection of knowing what it is that’s coming behind him. That’s what makes it very poignant. It’s not the fripperies of what we think as being important in life—this is the car I drive; this is the latest accolade I’ve got—or anything like that, it’s right down to those absolute raw core human characteristics of what matters in this really short existence that we’ve got on this planet. Often, we don’t realise that until we’re already at the eleventh hour.

I’m in my twenties and, when I was reading it, it felt like sitting down with a very warm elder who is teaching you how to navigate your relationships with other people. He has one of the most moving discussions of forgiveness that I’ve ever read.

He’s just incredible. He lives and breathes what he believes and what he stands for. I think it’s a book for all ages. The trouble is that it does tend to become a book for those who are thinking they are in the dying process. But as you’ve said so beautifully, it’s partly an instructional manual that says: I’ve got to the end of my life, here’s what I think is important, folks. If you know this at the beginning of your life, maybe you’ll take a slightly different part and get more out of this life than you would have done otherwise.

He talks about us being more concerned with the “postponement of death rather than the enhancement of life”. Do you agree?

Yes, I do. Absolutely. We are a little bit obsessed as a society—certainly as a western society—with saying ‘I need to live longer.’ I would like to live ten years longer than my life expectancy suggests but I don’t want it when I’m eighty; I wanted it when I was twenty. Living ten years longer when I’m eighty, into my nineties, may not be what I consider to be a quality of life. Trying to postpone death and making life last longer isn’t the same thing as living life better and living life for the moment. We do worry about living longer rather than living better—and we should be living better.

Finally, his discussion is intermingled with a lot of literary passages—lines from poems and philosophical reflections. You’ve got everything from Greek mythology to Nietzsche to Philip Larkin. Do you have your own favourite saying or maxim about death?

I’m not sure I could pick one. There are so many that, at that moment, actually feel right. There is a poem that we used to use in the memorial service which was about death: “So Many Different Lengths Of Time” by Brian Patten. It is beautiful because it talks about people living for as long as you hold them in your heart. One of the most important people in my life was my grandmother. She’s not dead because she’s still inside my heart and she’s still inside my head. For me, she dies when I die. That is a perfect circle for me. That poem reminds me every single time that we don’t actually have to let the people we love go because they do stay with us because they have impacted us—in our lives, in our hearts, and in our memory.

Five Books aims to keep its book recommendations and interviews up to date. If you are the interviewee and would like to update your choice of books (or even just what you say about them) please email us at [email protected]