For an opening gambit before we get to the books, what do you feel are the stereotypes that people hold of Tibet and how can we counter them?

As the conversation about Tibet slowly develops, particularly in the West, stereotypes proliferate, which at least means that there is wider range to choose from than in the past. They tend to depend on whom you’re talking to and their predilections. There is the western Buddhist approach – a view of Tibetan Buddhists as peaceful, harmonious and spiritually elevated, even mystical and esoteric. Another view is of Tibet as a society that was somehow eternally happy, like the idea of Shangri La in [the 1933 novel] Lost Horizon. That seems to be the view of those who have anxieties about modernity, and look to Tibet as a kind of haven.

More important now is the political perception of Tibetans as victims who have suffered great abuses heroically and non-violently, or the Chinese stereotype of Tibetans as brutally oppressed serfs who are rejoicing at liberation. These are just some of the stereotypes that abound, so there is some variety but it’s still a very one-dimensional picture. Whichever stereotype you take it leads you down a political cul de sac, and you end up demeaning Tibetans and not seeing them as intellectual or moral equals. These images tend to evaporate if you read serious writing produced by Tibetans within Tibet, or if you are able to talk in depth with people from there.

Give us a word, if you will, on the current situation in Tibet. Several monks self-immolated last year, and 2012 has already seen two confirmed deaths in Tibetan areas of Sichuan during clashes with police.

From a news and a political point of view, the situation in Tibet is reaching another trough, with significant instances of political unrest, violence and death. The last period like that was [with widespread riots] in 2008, and before that with protests in the 1980s. So these cycles are recurrent and seem to happening more frequently.

These events are partly a response to a very clear decision by China in 1994 to demonise the Dalai Lama. They had of course attacked him politically for many decades, since shortly after he fled Tibet in 1959. But it wasn’t until 1994 that they decided to attack him ad hominem, in a personal and religious manner – saying that he is not a true leader of Buddhism, he is personally responsible for the problems of society, and so on – and are still demanding now that all monks, nuns and officials formally denounce him.

That decision has led to what has been China’s second loss of Tibet, the first since it began the reform period in the 1980s, which introduced more open and relaxed policies. Now we are seeing the export of that anti-Dalai Lama policy from central areas around Lhasa – where the Chinese have been heavy handed in their policies for some 25 years now – to the eastern Tibetan areas. Those areas had enjoyed relatively relaxed policies and had been quite calm over the last 30 years, until the decision in the last decade to gradually force anti-Dalai Lama policies on them and their monasteries.

What do you envisage for the future? We hear chants of “Free Tibet”, but anyone who has been to or studied Tibet knows that is sadly unrealistic.

I hate to say this, but we have to learn from Wittgenstein and think of words not as a label that describes just one thing but as a signpost that points in various directions depending on the context. I think a lot of the people talking about freedom in Tibet, and outside of it, are not necessarily thinking of independence, or not only of independence. The more desperate the situation becomes, the more many Tibetans see the key issue as policies that erode their culture and identity, and for those, the idea of freedom probably is reduced to simply any kind of relaxation by the current regime – anything that diminishes the dominating role of Chinese in their everyday lives.

So for many of Tibetans the dream of independence and the memory of past independence is certainly strong, but may now take second place to more pragmatic aspirations. We can’t be sure of this, and it could change at any time, but it looks like a lot of Tibetans, perhaps most of them, would accept a compromise solution if the Dalai Lama could get one from China. Some would still like independence – it seems is that a rapidly increasing number view Tibet as having been independent in the past – but in the minds of many people almost anything is better than the policies in Tibet now.

Has the game changed with Lobsang Sangay at the political helm?

That’s a rather complicated story. Lobsang Sangay is a young man with a self-proclaimed “American” style of brash, pushy campaigning and loose rhetoric that is somewhat different from earlier Tibetan efforts to maintain careful, nuanced diplomatic relations with their foreign allies, or even from their more bullish attempts to push China to re-enter talks. But his ascendancy is symbolically very important for Tibetans, especially inside Tibet, because it confirms that the Dalai Lama has kept his fundamental commitment, unlike China, to complete the process of democratisation and to give over the role of government to an elected democratic leader.

In addition, Sangay is young, he is not from an aristocratic background, and he’s not even from central Tibet. He could do a great deal to improve the quality of Tibetan exiles’ education, administration and morale, but he probably can’t achieve that much with China, which has always, not surprisingly, refused to negotiate with an exile government that neither it nor any other country recognises. In terms of the bigger issues of Tibet-China relations, realistically these will still remain with the Dalai Lama. But they depend entirely on whether the Chinese will agree to resume talks. It’s been two years since they last agreed to meet, and now they say that the self-immolations are a form of pressure on them instigated by exiles, and so use them as another reason to delay the dialogue process.

Let’s begin on your book selection with Hisao Kimura’s memoir, co-written with Scott Berry, of being a Japanese spy in Tibet during wartime.

This was the book that really showed me how difficult it is for Westerners in particular and foreigners in general to talk or think about the Tibetan issue without introducing our own histories. We’re so deeply embedded in wishful thinking. But when you read Kimura’s account of living in Lhasa in the early 1940s disguised as a Mongolian – sent as a spy by the Japanese imperial government before the Second World War to report on possible routes for transporting arms that might exist in Tibet – then you see a foreigner, in part because of fluency in the language and the culture, who has the capacity to really enter into Tibetan society and language.

He writes about Tibet with a freshness and alertness to detail that is so invigorating. It’s partly because you sense that this man – even if he was a Japanese spy – really respected the people he was interacting with. Whether they were conservatives from the monasteries or radicals who were sympathetic to the Tibetan communists in Lhasa, he treated these people as if they were his intellectual equals, if not more. He didn’t follow the tradition that was so common at his time, including among previous Japanese visitors there, of looking down on Tibetans or of idolising them, which seems to be much the same in practice.

It’s also immensely touching because he becomes so engaged in the Tibetan society that he lives in that he effectively forgets his nationalistic mission to serve Japan, and has no news of what’s happening to Japan during the Second World War for almost all of the time that he’s in Tibet. He comes out in 1945, and discovers that his country has been defeated, and that everything he had been taught to stand up for had been a fascist dream and a disaster of its own kind.

I gather Kimura was in Lhasa at the same time as Heinrich Harrer, who wrote Seven Years in Tibet, and even sold Harrrer a pistol.

Yes! But the difference between them is so striking. For Harrer it seems to have been primarily a cultural experience, or semi-spiritual if you accept the version given in the Brad Pitt film. Harrer respected the people that he knew, but his writing tends to be about teaching them how movie projectors worked and how to dam a river or map a city. Kimura too described Tibet as a place where he met extraordinary people and learnt about this rather little-known culture, but he was able to talk to people as a fellow-thinker, to really listen to the different views that people had and to appreciate the intellectual discussions that were happening amongst Tibetans, in a way that was infinitely more subtle. He didn’t have a strong ideological project. He treated people as thinking beings. That’s surprisingly hard for most of us to do in such a situation, or at least to write about afterwards. We’re so easily seduced by the siren call of the exotic and the foreign.

Tell us about A Tibetan Revolutionary, and the context of those who viewed Communism as the way to modernise Tibet in the 1940s.

This is an extraordinary book, the first of its kind. It’s more or less the first time we hear the voice of a Tibetan still living in Tibet, in the form of an autobiography. In fact, it’s semi-autobiographical, co-written with the great American Tibetologist Melvyn Goldstein and a colleague, but even so it retains its distinctive voice, one that is crucial to understanding modern Tibet and its history. The person at its heart, Bapa Phüntso Wangye (sometimes spelt as Baba Phuntsog Wanggyal), was one of the main people whom Hisao Kimura knew in Lhasa. It was Phüntso Wangye who talked to Kimura about the democratic ideals of the Japanese constitution and their potential as a basis for a new Tibetan nation-state – not knowing that Kimura was himself Japanese and only disguised as a Mongolian.

This book is of great importance because here, even in the 1940s, we can see young Tibetan intellectuals like Phüntso Wangye already thinking: How can we modernise this society? How can we prevent the disaster of being swallowed up in the future? This biography describes Tibetan attempts to change their society and create a modern Tibet by themselves, a project that is underscored by the tragedy that followed from the 1950s onwards. Phüntso Wangye eventually found that he has no choice but to do this by working with the Chinese Communists.

He founded the Tibetan Communist Party as a young man, and then merged it with Mao when China occupied Tibet. Should we think of him as a collaborator?

He has been seen by more superficial writers as a collaborator, because he joined with the Chinese Communist Party in 1950 when they advanced into Tibet and then worked with them at a very senior level. But actually the book is quietly telling us about a very different story that couldn’t be spoken of until very recently, namely that Phüntso Wangye saw himself as his own communist, not as a Chinese one. He had become a communist secretly in the 1930s with less than ten other Tibetans, and it seems that then they had no intention of being part of the Chinese Communist Party. This book seems to be a carefully worded, and indeed dangerous, indication that the Tibetan Communist Party was founded by him and others as part of a vision of constructing a modern but separate Tibetan nation.

In 1950 they had no other choice but to change the name of their group to the “Tibet branch of the Chinese Communist Party”. As with other Leninists and communists in the early part of the 20th century, they didn’t really believe in nations taking over other nations. They thought this wouldn’t happen under communism, and that individual nations would be able to make their own futures, as the Chinese Communists had themselves promised in the 1930s. Phüntso Wangye believed this promise until the truth arrived in the form of the PLA [People’s Liberation Army] in 1950. And some seven years afterwards, even though he was then the highest level Tibetan in their ranks, the Chinese discovered that he had this internationalist view of communism. He spent the next 18 years in prison, all of it in solitary confinement.

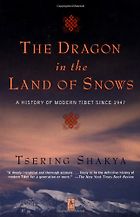

What is the outline of the history that Tsering Shakya is telling in this book?

It’s a history of a very weak state that is desperately trying to establish itself within the international community at a point when it’s far too late for it to succeed in doing that. The Tibetans had hidden themselves away from international relations ever since the British rejected their claims to have their independence recognised in 1913 – the British had instead recognised Tibet as being under Chinese suzerainty. This story of the Tibetan withdrawal from the challenges of modernity and their failure to establish themselves internationally is very well told in Melvyn Goldstein’s history of Tibet in the first half of the 20th century. Here Tsering Shakya, the leading Tibetan scholar of his generation, takes that history into the second half of the century.

He shows the efforts of Tibetans to reach out to the British, Americans and other Western powers at the time when they realised that Mao was going to win in China and come into Tibet. Then he shows the period after the arrival of the PLA, with an even-handed discussion of the Chinese attempts to deal with the Tibetans, at first quite carefully and then more aggressively. All these nuances are picked out by Shakya, at the same time as describing the responses of the international community to what was happening in Tibet from the 1950s up to the 1980s, and the dramatic, disastrous efforts to transform Tibet into a revolutionary socialist society after 1959. The book is a very careful, detailed study of all these questions.

Let’s discuss that period after 1950 in more detail, by way of Tubten Khétsun’s autobiography Memories of Life in Lhasa Under Chinese Rule.

This is the first Tibetan autobiography to come out in English that isn’t mediated by a ghost writer, translated from the author’s text by a the gifted Tibetologist, Matthew Akester. Here we have the direct voice of Tubten Khétsun, who had left Tibet in 1983 but is able to talk about what happened in Lhasa in the 1950s, 60s and 70s with unusual precision. For the first time in English we get a sense of the detail, of the smallness of historical experience for those who lived through it. Not everything consists of massive episodes and crises such as those we read about in newspapers or normal histories – a revolution here, a massacre or atrocity there. Instead we are given insight into the nature of extreme control that continues over decades, its banality and its everyday effects.

Tubten Khétsun was in prison for 20 years, and suffered terrible deprivation and abuse. But he talks about small things, like the incessant desperation of the Chinese cadres to impress Tibetans with good works, as with the irrigation of fields where hundreds of Tibetans were forced to dig canals that went uphill. At other times they were made to dig terraces on mountainsides to grow rice where nothing would grow, or add chemical fertiliser to their crops because this was seen as modernity, while actually it made the ground dry up.

These were outcomes of the conviction of the Chinese that they were helping Tibetans by imposing modernisation on them – the endless, grinding detail of the everyday blindness of authoritarian benevolence. You see this on every page of the book, and it’s told as much through dark, sardonic humour as through condemnation. But at the same time, it helps us understand why officials promoted such policies, and why it is still so hard for them to accept criticism.

The typical Chinese view of trouble in Tibet today is still that protesters are biting the hand that feeds them.

I think it’s likely that many of the terrible experiences that people have under the Chinese or any other authoritarian system come in the form of everyday issues, and that these probably seemed well-intentioned to those who imposed them. I suppose we all have to learn to remind ourselves of other perspectives in order to see how such outcomes eventuate. Wide reading seems one of the best ways to do that. It’s also crucial to talk to people who have lived inside situations rather than outside them. So I feel we have to privilege books like this one, where a writer, even in profound disagreement, can still indicate how the Chinese thought they were doing good, as many of them are still convinced that they are.

As outsiders, I think we have to factor that into our judgments, while still making criticisms and proposals as appropriate, in the hope of finding ways that can be heard by the other side. Of course the Chinese did bring some benefits to Tibet, along with the damaging effects of their policies in many other cases. So perhaps it’s a question of articulating ways to talk that don’t cut out these other perspectives and the Chinese sense of purpose, or diminish that of Tibetans and others who live there. I think we can learn to do that, and perhaps it can produce a better, more effective kind of politics.

Your final choice is something more literary, a collection of contemporary Tibetan stories. Why did you choose this?

When we read literature about Tibet in English we don’t hear many actual Tibetan voices, besides those from exile; it has been relatively rare to hear from Tibetans inside Tibet. Tibetans who have been brought up under China, and who know China and its language well, don’t necessarily have any animosity towards its culture or its peoples, whatever they think of its policies. Or, even if the pain they have undergone is unimaginably great, they may not consider that such a view needs to be displayed in public – a balancing of considerations that deserves to be taken seriously. There are so few books in translation which offer us that kind of voice, but they are increasing, luckily, thanks mainly to young Tibetologists who are translating such works into western languages.

This is a translation by a Finnish scholar, Riika Virtanen, of four short stories by leading Tibetan writers inside Tibet written in the 1980s or shortly after. They’re not political stories – they’re published inside Tibet and they don’t necessarily have strong political agendas. Even if they had, the authors couldn’t have written openly about them. Maybe they don’t think in binary or polar ways about their situation, which after all was infinitely better for them at that time than what they had lived through in the sixties and seventies.

Instead, these stories are about everyday life. One, by the famous eastern Tibetan writer Dondrup Gyal, is about marriage in Tibetan villages in the countryside, where culture and social behaviour has remained very traditional in many ways. Should Tibetan village society still be forcing women to have arranged marriages, or should they be allowed love marriages? It’s a tragedy about a woman forced to marry someone she doesn’t want.

Another, by the Lhasa writer Tashi Palden, is much more contemporary. It describes a young Tibetan girl from the countryside who has been brought into a modern, wealthy Tibetan house in the city as a domestic maid, made to work inhuman hours and then seduced by the man of the house. It’s a kind of Tibetan Tess of the D’Urbervilles in miniature, but entirely contemporary. The exploitation of young women from the rural areas is an important issue in Tibet today, as one of the major Chinese policies in Tibet has been to make the urban Tibetan middle class far wealthier than before, presumably in the hope of increasing their loyalty to the state, at the same time as encouraging rural youth to look for work in towns. The enrichment of the middle class is not a policy that anyone involved in objects to, of course, but the social side-effects and the exploitation that it has nurtured have rarely been discussed.

So although these stories don’t discuss politics directly, it’s immediately clear how important they are and how they raise major moral questions about what it means to be a Tibetan in modern, evolving and inwardly conflicted Tibetan society.

And what does it mean? What is Tibetan identity in the 21st century? Is it disappearing?

When we look at novelists and filmmakers coming from inside Tibet, the less they talk about politics – which most of them can’t safely do – the more we see nuance, depth and complexity in their articulation of the issues around developing a modern Tibetan identity. There’s a huge and important discussion going on among Tibetans about how much they have to trade in of their traditions and cultural norms in order to be effective as a people in the modern world. That debate is as or more important than the one over who’s going to be their political ruler, a debate they’re basically doomed to lose. And in Tibetan literature we can see some of the details of that debate over identity and modernity – how much has to be given up and how much can be retained.

Among the intellectuals – especially those educated in Tibetan but also among many of those educated in Chinese – there is a very rich sense of Tibetan identity and cultural commitment. I would guess there are more poets per population in north-eastern Tibet than perhaps anywhere else in the world. So there is a thriving commitment to expression, to working out ideas through verse, literature, art and film. Although aspects of Tibetan culture have been targeted by the Chinese state for serious containment and repression, these areas have flourished. But can these intellectuals convey that kind of vision to Tibetans who have much less education, and who are struggling to survive, caught up in either consumer society or in the bureaucratic job market, or just struggling to work in construction or as farmers or traders?

That is the question: What’s going to happen when the whole of Tibetan society faces modernity? Will it be able to find the subtle answers that the intellectuals are exploring? There’s not enough discussion about that, whereas an awful lot gets lost, at least in exile, in discussion of the big political issues like protest, imprisonment and attempts to resist Chinese rule. That fight often doesn’t allow for the detailed study that could be given to these larger cultural questions, which all Tibetans have to deal with every day.

What bon mot will you leave us with, to remember next time we think of Tibet?

Well, perhaps we could sum this up by saying that when Westerners and outsiders talk about Tibet, we tend to be speaking in shorthand about China’s right to run it, because the ability of nations and states to persist is fundamental to our deep and necessary anxieties about the viability of the international system. We sense that principles have to be urgently maintained to avert the Hobbesian outcome. But we can also gain by recognising the value of more quotidian discussions about Tibet, which may have little or no immediate impact on our own countries. These we can encounter through conversation with Tibetans, Chinese, Muslims and other people inside Tibet, and even more so through their books, that allow us to follow their discussions among themselves.

Then I think we can gradually become familiar with other questions, ones that might perhaps be even larger for them. Language, religion and education are probably key issues for most Tibetans. Debates over the meaning of “development” and “modernity” are crucial too, just as they are for us. If they can work out those issues, they can work out the other questions too, if only China will allow them to do so. But of course it’s difficult just now to see that happening.

——————————————————

Also recommended on Five Books (by Evan Osnos of the New Yorker):

Interview by Alec Ash

February 1, 2012. Updated: August 9, 2024

Five Books aims to keep its book recommendations and interviews up to date. If you are the interviewee and would like to update your choice of books (or even just what you say about them) please email us at [email protected]

Five Books interviews are expensive to produce. If you've enjoyed this interview, please support us by donating a small amount.