Last year’s Super Bowl netted nearly 163 million viewers. Has football taken the place of baseball as America’s favourite pastime?

There’s no question. The interest is greater and the sport fits the personality of the United States better than the lazy pastoral aspect of baseball. TV has embraced the brutal elegance of football. The replay and slow motion effects make the game mesmerising to watch. So I’d say, “Absolutely!” It’s replaced every other sport as America’s favourite pastime – soccer never came close; boxing used to be a big deal, and basketball remains important, but it’s nothing like football.

You played college football and you’ve written about the sport for nearly 40 years. How, specifically, does the sport suit the personality of the United States?

Football entails being aggressive, being independent and taking what you want within the rules. The United States was formed by intrepid individuals who came to stake a claim. They didn’t wait for a land grant. And, like football, there’s a lot of violence in the United States. We have more guns than anywhere in the world and a huge part of the reason why is that we don’t want to be controllable, certainly not by government. Americans like to live right up to the edge of our laws. It’s the same with football – a lot of violence is within every person on the field, playing up to the edge of the rules.

In football, beauty, violence and sex are mixed. The game is beautiful to watch in replay – there is violence in almost every play and then they cut to half-naked dancing girls shaking pom-poms. It’s a uniquely American television spectacle.

Some of our readers won’t be initiated in the pleasures of football – can you just brief us on them? What is the essence of the game, what makes it so interesting to so many people?

It’s all about aggression – that’s the essence of football. If there were no rules these guys would just kill each other. Two teams face each other on the line of scrimmage and try to move into their opponents’ territory. It’s like a battlefront – trench warfare without weapons. All the rules – offside, penalties, motion rules and passing rules – make it complex but the essence of it is very simple: We’re going to go as far as we can toward a goal and you’re trying to stop us. It’s about taking the ball or territory however it has to be done and making it yours as you move up and down the field. In soccer and hockey the line of scrimmage is less precise. In football you can score at any time, through an interception or fumble. I don’t think there’s another sport like it.

American football has been compared to chess on a playing field. Please clarify the comparison.

Chess is a board game, but it’s clearly one of aggression like football. Dumb aggression doesn’t work in chess and it doesn’t work in football. In chess many moves invite mistakes from opponents and in football many plays are based on anticipating an overly aggressive response from the other team. In both the game and the sport, you plot 10 plays ahead and wait for one false move to open up a king for checkmate or the field for a deep long pass. In both games you’re always looking to take someone out, whether it’s your opponent’s knight or your opposing team’s running back. They are extremely analogous, except in football the violence is real and in chess it’s make-believe.

I’m looking forward to learning more as we discuss your five book selections. A college coach’s story seems like a good place to start. Introduce us to Bootlegger’s Boy, a memoir by Barry Switzer.

I covered college football during the 1970s, 80s and into the 90s, so I knew Barry Switzer, the legendary coach of the Oklahoma Sooners, quite well. He was a unique one and Bootlegger’s Boy is the unbelievable true story of his upbringing and triumphs on the field. It’s great reading.

As the title says, Switzer was the son of a bootlegger. His dad would occasionally fire a pistol through the ceiling, Barry’s mom shot him and he died in a car crash. Barry had as awful an upbringing as anyone could have and yet he ended up running the number one college football team in the country.

He always believed if he got the best players he could win and propriety be damned. He found kids who wouldn’t get a chance at another school and led them to play to the limit of their potential. He had a quarterback named Charles Thompson, back in the eighties when they were number one, a little guy, whom Switzer had first seen breakdancing on a piece of cardboard at a car dealership in Lawton, Oklahoma. This kid becomes his starting quarterback as a freshman and led the Sooners to a great record but ended up being arrested, indicted and found guilty of distributing cocaine. Switzer found a lot of kids like Charles Thompson who wouldn’t get a chance at some other college. As he said, “the magic was in the players”.

College football is big business in the US. The games are televised nationally, the athletes become celebrities and the merchandise is marketed as professionally as in the NFL. You played for the Northwestern Wildcats in college, a Big Ten team. What exactly is the Big Ten and how important are university football programmes to the sport overall?

It’s a peculiar part of the American system that big money athletics are part of universities. Spectator sports are tied into university life in a way they aren’t in Asia, Europe or South America. They see the Big Ten as bizarre and they’re right. University should be about higher education, yet sports can produce a lot of revenue for an American college. It’s part of our tradition here – it probably shouldn’t be, but it is.

The Big Ten is a 115-year-old, 12-school intercollegiate conference that embraces big land-grant state schools in the Midwest – including Indiana, Iowa, Illinois, Minnesota, Michigan, Nebraska, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin – and has a big academic aspect to it, but it’s synonymous with Division 1 sports.

Let’s turn to the memoir of a college player turned pro-linebacker for the Saint Louis Cardinals. It was called “the first critical look at the dehumanising aspects” of the sport. Tell us about David Meggyesy and Out of Their League.

When I was a kid I remembered Dave Meggyesy playing. In the United States – when I was growing up and to this day – kids are sold on the notion that sports stars are heroes, coaches are father figures and on the sports field the best man wins, good overcomes bad. There’s this Disney-like idea that if somebody wins, they must be a good person. In his book, which was published in 1971, Dave Meggyesy shatters those myths. He writes about the brutality of the game and the cruelty of coaches. He makes clear that winning comes at a steep price.

Specifically, he talked about the demeaning of players. Sexuality was something that he brought up – the point that in sports, and particularly in football, if you don’t do something you’re called weak, you’re called a coward or, worst of all, you’re called a female. That was constant. He shows how violence was legitimised and how players would do anything to please coaches. He writes, “I developed a style the coaches loved. We moved in Oedipal lockstep: The more approval they gave me, the more fanatically I played. From an early age, I learned to endure violence and brutality as simply a part of my life. But in football, the brutality became legitimate, a way of being accepted on the football field and off it.”

Reading that made me realise that although I loved to play in grade school it was going to get nasty. And it did but I couldn’t say I wasn’t forewarned because I read Meggyesy. He is still alive. He became a left-wing activist and union organiser.

Meggyesy seems to focus on the dark side of the game. What do readers of Out of Their League learn about the essence of football?

It’s a cautionary tale. It reminds you not to let your humanity get usurped by people who can get what they want by being cruel. If you’re a coach for a brief time, you see you can make people do inhuman things. As we’ve seen in wars, you can make people torture and exterminate others. So on the football field you have to be careful not to lose your humanity. I think he was the first guy to really make that clear. It was tremendously influential to me, and I think to a lot of people, to have a guy like Dave Meggyesy writing this stuff because nobody else was.

Did you feel dehumanised as a college player?

Yeah, very much so. Football and boxing, by their very nature, get right to the edge of what human beings should be allowed to do to each other. A lot of people say they should not be allowed. In football you don’t get points for hurting someone but there come times when injuring or blindsiding an opposing player can help your team win. Whether it’s a concussion or a blown-out knee, you can end up injuring someone for life. The sport is dangerous. Our heads are in the middle of our shoulders – there’s no way to tackle somebody without your head being involved. You have to be clear about when you’re acting more like a battering ram than a human being.

Let’s turn to two books that became successful films in the seventies, starting with Semi-Tough by Dan Jenkins.

Semi-Tough is the funniest satire of the sport I’ve read. All the fiction before was Disney stuff, about the sports hero winning one for the crippled kid – not about the sports star drinking 40 shots while trying to get laid. There’s a lot of locker-room and bathroom humour in this book. Some of it is X-rated, but it’s also more serious. Dan Jenkins satirises the ugly aspect of football that Dave Meggyesy brought out through non-fiction.

It makes you laugh at things that were politically incorrect while making you realise that they’re wrong. It was a revelatory type of writing that had not been done before by anybody. It’s a really smart-ass dirty playboy aspect of the sport and he brought that out.

The protagonist of this novel, Billy Clyde Puckett, is a Texas-born halfback for the New York Giants. The next novel you named is about the Dallas Cowboys. What is it about the Lone Star state that makes it such an incubator for football?

Their slogan – Don’t Mess with Texas – might say it all. It’s an oversized aggressive state, the biggest state other than Alaska. Everything is huge. The Cowboys came to embody the state. Their original coach, Tom Landry, was a God-fearing Christian and the team was filled with rebellious sex and drug-crazed athletes who were almost sanctified. They were called America’s team.

Once you get out in the plains of Texas, whole towns get wrapped up in the game, as they showed in Friday Night Lights. Teams became symbols of success for whole towns. I’ve been a lot to Lubbock and Midland and it’s really something to behold.

Dan Jenkins comes from Texas, Fort Worth. Then you get a guy like Pete Gent, who was from the Midwest but joined the Dallas Cowboys. He was a very literate person, one of the first athletes I can think of to write a book. He wrote about what he saw from the inside in North Dallas Forty.

Which was the next book I wanted to ask about. First published in 1973, it seems like a more serious novel about the seamy side of football. Please introduce us to the book and its author, a former wide receiver, Peter Gent.

Even though the team in the book is called by another name, it’s obviously about the Cowboys. North Dallas is where the Cowboys were located and Forty refers to the 40-man team roster. It’s barely fiction. The book gets a little confused at the end but the first half of it is absolutely brilliant.

It’s about a main character who is a wide receiver – it’s clearly Pete Gent but he’s called Phil Elliott. Everybody has a pseudonym, but you can tell who’s who. Phil Elliott becomes more and more disillusioned with all the drug taking and all of the incredible immorality of the players – the guns, the lying, the cheating, the abuse and rape of women. And he finds it harder to manage the incredible amount of pain he endures from what he does on the field. Players are being used almost like gladiators, until they’re of no use to anybody any more. The main character finally comes to the realisation that the only way he can get relief is to leave.

One reviewer wrote that this book let’s you know what it feels like to play the game. Does it leave you aching?

Yeah. He describes getting up in the morning as a process that takes maybe an hour – easing into a hot tub, slowly stretching certain joints and then taking a bunch of painkilling drugs. It’s horrible – almost hard to read. I talked to Pete Gent one time and asked him, “Was it like that when you got up in the morning?” And he told me, “Yeah.” I know it’s true for many players.

We’re coming to realise how crippled and tortured and pummelled these players become, that joints and bones pay a price. And now we know, more and more, what happens inside the head. We see suicides, early onset Alzheimer’s, Lou Gehrig’s disease, loss of memory. So many players in their late forties and fifties and certainly by their sixties are mentally and physically incapacitated from playing the game in their twenties.

Pete Gent wrote about that before others did and, of course, when you write things like this, when you tell a truth nobody wants to hear, you’re ostracised. And he was. He was considered an outcast. He was considered a whistle-blower. He was attacked personally and ridiculed. Sadly, Pete Gent died. I wish he was alive to see that people are finally paying attention to the things he gave warnings of.

The medicine chests of Gent’s characters are filled with uppers and painkillers. Was football that drug-dependent and is it still?

Yes. When you tackle somebody with your shoulder it’s as if you rammed your shoulder in a wall, so there’s going to be bruising and inflammation and slight dislocation of things on every play. Every hit in the NFL is the equivalent of what a normal person will go through in a minor car wreck. So you have to do something.

So there are players who admit to taking drugs and there are those who say they don’t, but are lying. You’re masking pain all the time. You have to play in pain. Somehow people think it’s OK for these guys to get the shots, the numbing shots and the anti-inflammatory shots. Toradol shots, which is the new rage, they get all the time, routinely, every game. And we know that. Whether you’re a Bears fan or a Giants fan, whoever you root for, they’re all getting shots, they’re all taking pills while they’re playing, and when they’re done they’re left with the pain and addictions.

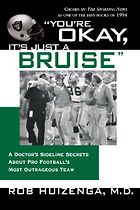

A memoir from a football physician is your next selection. Tell us about the autobiography of Los Angeles Raiders internist Rob Huizenga.

In this book Dr Huizenga divulged the incredibly damaging things that team doctors did to get players back in the game. Not things that were good for the player’s health; things that were good for the team and the owners. In his view, the coaches, the owners and the doctors themselves were in cahoots. They did not care about the players’ wellbeing, they did not care about their mental health, they did not care about their physical health because they had to win. The job description of the team doctor was not to make the players better; they’re there to help the team win. So if somebody is crippled in the process of making a touchdown, they’ve won that game for you and if you have to cut them that’s fine. Huizenga was the first person from the medical profession to explain all that.

He talks about a neck specialist from Philadelphia named Dr Torg who cleared a player to play after other doctors urged the athlete to retire or get surgery. He talks about Dean Steinkuhler, a tremendous player for the Raiders, who had 13 knee surgeries and another guy, Mike Munchak, a great player too, who had nine surgeries on his right knee alone. This is while they’re playing, so any doctor could warn, “You guys are crippling yourselves.” Huizenga watched all this and felt guilty about it. The Hippocratic oath says first you do no harm. Well, team doctors were doing harm.

Dr Huizenga resigned in disgust.

You either endorse what you see or you have to leave it. He saw that the medical staff’s mission was to help the owner because that’s why they were hired. He said, “I’m not going to do it.” And so then he wrote this book about it and the thing is nobody cares. It’s like, nice read, but nothing will change.

In a series of recent suits, dozens of former NFL players are seeking damages for brain trauma they suffered on the field. Will the game change because of the new focus on brain injuries?

Well, it’s been forced to change but not because people care. The insurance aspect of it has made the NFL do something and made parents more aware. But the obviousness of this has always been there. You can’t hit anything, including people, with your head without sustaining damage.

Most kids just quit, they play football for a while and they may be tough but they will say there’s something wrong with this sport. Something inside of them will tell them that, “This isn’t right. I don’t mind getting my knee injured or my ankle, my shoulder, my hip, my hand, or my wrist. But my brain? This is my essence, this is who I am and that’s not something to mess with.” We haven’t really identified what a person is but there are people who played football and when they’re done they’re not the same any more. They might be willing to risk it at a young age. But even one concussion can have an impact. Doctors are saying no amount of padding for the head can stop a concussion because a brain is loose jelly inside of the skull. The skull may not break, but the brain still collides with its sides and that concussion causes damage. One time of being knocked out cold – the bleeding, the trauma, the bruising – it can hinder you for life.

So what we get to is: Is this game playable? Concussions happen all the time. Is that something that should be tolerated? Guys will say, “I’m a gladiator.” Well, being a gladiator was outlawed a couple of thousand years ago. Civilised societies do not have gladiators. We’ve outlawed a lot of things. We don’t duel with swords any more. We don’t allow people to go out in the street and shoot each other. We recognised if we allowed these things, we would lose something as a civilisation. That’s the point we’re approaching in football. Nobody wants to acknowledge the obvious because it’s a wonderful game. Ninety-five per cent of it is within civilised bounds, but that 5%? It is a wonderful game but, knowing what we know, maybe we shouldn’t play it any more.

Five Books aims to keep its book recommendations and interviews up to date. If you are the interviewee and would like to update your choice of books (or even just what you say about them) please email us at [email protected]

Five Books interviews are expensive to produce. If you've enjoyed this interview, please support us by donating a small amount.