I’ve just spoken to Tom Gauld about comics. But, whereas Tom Gauld is a cartoonist, you have been studying cartoons, or graphic novels, from a theoretical, academic point of view: a new discipline and you’re at the front of it. So where should we start?

Well, I wouldn’t call them graphic novels. I’d call them graphic narratives or comics, because all of the stuff I’m interested in is non-fiction, so ‘graphic novel’ is simply a misnomer for this kind of work. Also, it’s a publishing, marketing term and a lot of cartoonists don’t like it. It seems like a kind of shallow bid for respectability. So let’s say comics.

You’ve chosen Fun Home by Alison Bechdel to start with. What’s it about?

Alison has a strip that’s been running for a long time called Dykes to Watch Out For, but this is an autobiographical book. ‘Fun Home’ is short for the funeral home Alison’s dad ran when she was a child. It’s a book that blew me away and continues to blow me away every time I read it – and I must have read it five or six times by now: probably the best book I’ve read in the past ten years in any genre or form. It’s an incredibly crafted book in which the chapters are not chronological but thematic, and each chapter is keyed to a book that her father loved. So it’s not a book about what happened to her father, a closeted gay man who committed suicide a few months after Alison herself came out when she was 19. It’s about looking through a family archive to try and get a sense of her father’s particularity.

Does she talk about her father’s suicide at all?

She gives the plot away right at the beginning. He jumps backwards in front of a truck on the Pennsylvania highway, and the rest of the book is this incredibly moving, powerful investigation of her own childhood. An adult investigation of a family archive of documents, photographs, diaries, objects, which belonged to her father. She’s searching for his identity; how she can relate to him and where the points of disconnection are. She’s investigating what the lived life of her closeted gay father must have been like. But part of what’s fascinating to me about the book is that she redraws the archival material by hand: the photographs, the letters, the police reports, even her own childhood diaries.

Why?

When comics are interesting, they’re a hand-made form. That’s the connection between comics and autobiography. On every page of the comic you have an index of the body of the person making it. I think redrawing all these documents gives her a way of going back into her family history and marking it with her own body. It’s an amazing act of self-possession – taking control of the archives, making a shadow archive, mimicking. It’s very much about being a child – what it’s like being a child relating to parents.

You’ve done a lot of work with Art Spiegelman, but you haven’t chosen his most famous book, Maus, for your list; Maus being Spiegelman’s account of his father’s experience in the German death camps – perhaps one of the most influential accounts of the Holocaust next to Primo Levi’s If This is a Man. Before you tell us about Breakdowns, can you tell us why Spiegelman became famous?

I would say that Art Spiegelman is the most famous and influential cartoonist alive. And I would also argue that he’s the most important figure in the literature of the boomer generation. Paul Auster and Art are friends, and Art nominated Paul when I suggested this to him. The publication of the first volume of Maus in 1986 was absolutely a terrain-shifting moment. It was nominated for a National Book Critic Circle award in the category of biography and people freaked out. In 1991, the second half was on the New York Times bestseller list on the fiction side of the ledger. Art wrote a letter to the Times complaining and, for the first time in the history of that list, they published his letter and moved it to non-fiction. So it’s this pushing on taxonomy that Maus accomplished and which fascinates me so much. Maus changed the face of comics and also modern literature.

Tell us about Breakdowns.

Breakdowns was first published in 1978 in an edition of 5,000 copies, 1,000 of which were ruined in an accident at the printers. For years it’s been a rare, coveted book, so when Pantheon republished it in 2008 it was unbelievable. I remember seeing a used first edition of Breakdowns in a New York store for $375 and it was on sale. It was the book everybody wanted but couldn’t afford, and now it costs $27.50.

Five Books interviews are expensive to produce. If you're enjoying this interview, please support us by donating a small amount.

What’s all the fuss about?

This book collects all of Art’s work from the 1970s, when he was really pushing on received notions about what comics as a narrative form could do. Broadly, the comics in Breakdowns are heavily modernist or avant-garde comics. They play with conventions of time, space, causality, setting the bar very high for comics quite early on. But a lot of people haven’t been aware of Breakdowns until recently, when the Pantheon edition came out. It’s a collection of several different stories, one of which is a three-page version of ‘Maus’. There’s ‘Prisoner on The Hell Planet’, which would later appear in Maus. But there’s also ‘Cracking Jokes: A Brief Enquiry into Various Aspects of Humour’, which is kind of the first comics essay, featuring, amongst other things, Freud as a character. It’s Art really going out on a limb, without a supporting culture already there, taking comics as far as they can go.

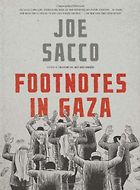

Which presumably contributed something to your third choice, Footnotes in Gaza?

Joe Sacco is the foremost figure in what he calls ‘comics journalism’ – he really established this category. He’s done several other really powerful and important works, like Palestine and another about Bosnia. But what’s so powerful to me about Footnotes in Gaza is the way it examines an event that happens in the past, and the way that event has affected the present and is affected by the present. The relationship is really on the surface. He conducted a lot of research about 1956, a lot of research into the massacres that happened then, and then he drew them. He makes his investigation really explicit, the business of both writing and drawing the past. So, for example, he includes passages where he’s tracking down the very few remaining survivors of these massacres and he fills out their testimonies with his own sense of what their accounts would actually have looked like. Spiegelman calls this ‘materialising the past’. In Maus, Art materialises his father’s and his own history. And in Footnotes in Gaza Joe Sacco is interviewing people and doing his own research and then very meticulously materialising this history.

Your last three books have been explicitly historiographic, but it sounds like your fourth book is a bit different.

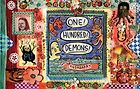

One Hundred Demons, yes, I suppose. Though it’s still reflecting on history. Joe calls his work ‘comics journalism’. Lynda Barry calls hers ‘autobifictionalography’. Which I think is brilliant and hilarious. So on the table of contents page, which is this beautiful, dense, colourful collage, she draws two check boxes after the question: ‘Are these stories true or false?’ She ticks both. She’s interested in telling us from the very beginning that she’s subjective.

What are the stories about?

Well, the content’s pretty dark: suicide, sexual abuse, so forth. One’s about growing up in a Filipino family with neighbours that aren’t. It’s not for children, but it’s definitely about children. What I love about this book is that, like Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home, it’s a life story but it isn’t told chronologically. It’s told thematically, so there’s one chapter that’s called ‘Girlness’, another called ‘Head Lice and My Worst Boyfriend’. It’s a constant circling in to certain issues, and each chapter is preceded by a beautiful, dense, two-page collage. It’s a book meant for a wide audience but which also contains these stand-alone art pieces. It’s also one of the funniest books I’ve read in my entire life.

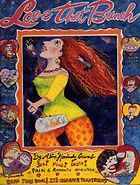

Finally, tell us about Love That Bunch by Aline Kominsky-Crumb.

I just met with her in France.

Two great cartoonists living together. Because she’s married to Robert Crumb, right?

Yes. To me, Aline is one of the most important figures in comics, which isn’t to say that she’s one of the most well-known. She’s not. But her comics have inspired a legion of cartoonists working in comics autobiography: specifically women cartoonists, because Aline published the first ever autobiographical comic from a woman’s point of view. Robert Crumb says she’s inspired him to be more confessional, and you can see that in the trajectory of his work. They did a comic together called Dirty Laundry Comics, which came out in 1974, but was collected as a book in the 90s. Norton’s republishing them all now. But Aline has a style which I find wonderful, and which a lot of people find really off-putting and ugly. She calls it scratching. She talks about her raw scratching. Crumb’s fans love his cross-hatching and they wrote terrible letters to him saying things like: ‘She may be a great lay but keep her off the fucking page,’ or ‘You do the cartooning, keep her in the kitchen.’

Get the weekly Five Books newsletter

How does her style look to you?

It’s conscious of its own struggle. I love the shakiness of her line. I love how expressive it is, how bodily. And her work really focuses on the body. She once did a cover to a comic called Twisted Sisters in which she drew herself sitting on the toilet with a plate of food near her looking in a hand-held mirror. I find it funny and powerful and a lot of people found it off-putting. But that was in the 70s when feminism was all about idealising the female body. Aline, by contrast, draws on a long history of Jewish comedy, and a sardonic world view in which self-deprecation is at the centre of a lot of the humour. It’s very serious but also satirical and I guess a lot of people don’t, or didn’t, understand her tone. It’s a cultural critique, not self-abasement. She’s called herself ‘the grandmother of whiny, tell-all comics’.

February 6, 2010. Updated: February 10, 2023

Five Books aims to keep its book recommendations and interviews up to date. If you are the interviewee and would like to update your choice of books (or even just what you say about them) please email us at [email protected]