Tell me about your first book, The Riddle of the Sands by Erskine Childers, which is seen by some as the first modern spy thriller and said to have inspired the likes of Graham Greene and John le Carré.

Yes, it is a wonderful book both for the espionage aficionado and also for the yachtsman. It testifies to the fact that if you are writing any novel with a technical basis, it is good to do research and get it right. This is the only novel he wrote; he went on to become a very committed political fellow.

It is basically a serious novel about a sailor called Davies who invites a friend to join him sailing around the German coast from the Baltic to the North Sea. The narrator is Carruthers, a civil servant who works in the Foreign Office, and he is at a loose end in August because everyone has gone away. Suddenly he gets this invitation to go yachting from someone he used to be at university with. He packs his white shoes, cap, blazer and white trousers, only to discover when he gets there that this is not how it is going to be. Instead it is a rather dirty, two-man sailing boat. What they do is sail around the Frisian Islands and discover that the Germans have been building up resources to invade England. So there is this kind of mystery gradually unfolding as they explore those sandy channels in Germany’s North Sea coast.

Published in 1903, the book was one of a series of scares that alerted the British public about the possibility that Germany might be up to no good. At this stage Germany was England’s chief European challenger. Safely protected by living on an island, the British traditionally didn’t get much involved with the continent of Europe and remained in ‘splendid isolation’, secured by the Royal Navy, the greatest in the world. But after Germany united in 1871 it began to take on global ambitions and try to emulate Britain by looking for colonies all over the world. And they began to build a world-class navy that many suspected was to use against Britain. There is this idea that they are sending in spies to Britain to work out their weaknesses. And there is a concern there might be a surprise attack on Britain’s undefended East Coast. This novel is one of the first that focused people’s attention on this.

By 1909 these worries have percolated into some members of the government, and one way of meeting the danger was to set up a new Secret Service with a home department to look for German spies in Britain (which turned into MI5) and a foreign department (which turned into MI6). They were both founded at the same time in October 1909. And the MI6 job is, of course, to spy on Germans in Germany and see about German capabilities and intentions.

Your next choice is Greek Memories by Compton Mackenzie.

Compton Mackenzie was a humorous novelist and enormously prolific Scottish writer as well as being a public man of affairs. He had already achieved a reputation as a novelist just before the First World War. But during the war he joins the Navy and goes to serve in Naval Intelligence in Greece after being invalided out of front line work. He was taken on by the forerunner of MI6 – then known as MI1c. It was run by a wonderful man called Mansfield Cumming, who hired Mackenzie to run his Greek operation, which was primarily to gather intelligence about the political situation in Greece, which was neutral at the time.

The Germans were backing the Turks at this stage so there was a lot of anti-British activity in the Aegean Sea, which is where Mackenzie was based. He does very well and gathers a lot of information from 1915-1917. He was sending back these witty reports, sometimes in blank verse, which Cumming rather liked but others rated as too light-hearted.

This book was one of the first show-and-tell books to come out of the Secret Service.

Yes, when it was published in 1932 it was almost immediately withdrawn and he was prosecuted under the Official Secrets Act. It was one of the first sensational memoirs of a former spy, revealing details of his Secret Service. But actually he didn’t divulge very much at all. He revealed that the head of the Secret Service used a single initial C and that he wrote in green ink! And that is still the case today. He also named a number of people who worked for him, and that is what got the organisation so rattled because they don’t like people telling tales out of school. MI6 is an extremely secretive organisation; the people who work for it are secret. But Mackenzie said, look, this is 1932, and it is 15 or 16 years since I was doing this, so no damage has been done. But the organisation thought very differently. They didn’t like the principle of revealing names.

That problem continues today.

That is precisely it. Mackenzie’s book was the first high-level manifestation of a continuing problem for the Secret Services. There are people going off track and trying to exploit their time in the Service for private gain and self-publicity. The trial when it came had its humorous aspects. Mackenzie got someone from the Foreign Office to say he didn’t think there were very many secrets revealed at all.

The same thing happened with the Spycatcher trial in 1986 when the government ended up with egg on their faces, looking stupid by pursuing secrecy for secrecy’s sake. There is a balance that needs to be struck. And of course MI6 didn’t itself exist publicly until 1994. That is 80-plus years into its life. If you had asked someone in 1993, ‘Does it exist?’ they would say, ‘I can neither confirm or deny that’, which was – and is – manifestly absurd. Compton Mackenzie made great play in his memoirs on this absurdity and got his revenge after the trial by going on to write a satire about the situation in a novel called Water on the Brain. It described a very secret department of government, which worked in a building which was to become an insane asylum for civil servants sent mad in the service of their country, which is a good read.

There are so many James Bond books to choose from – what made you go for From Russia with Love?

The James Bond books represent the other end of the spectrum. These are cartoon characters in a way, but they produced the most famous single fictional spy who worked for MI6. Bond is very important. It is also quite difficult to extract the novels from the movies because we sort of visualise them. But From Russia with Love is on my list for two reasons. The first is it is the only one with an Irish angle and I am always looking for the Irish angle. And the second is there is a clear connection to Fleming’s work as an intelligence officer in the Second World War.

The Irish angle is Donovan or ‘Red’ Grant, a Smersh killer, who in the movie is a blond powerful figure who goes round killing people at the drop of a hat, which of course is one of those myths about the Secret Service that people are always killing each other just like that, and that everyone has a ‘licence to kill’…

According to the book, Grant, this Russian killer, is the son of an Irish mother and a German circus strongman. Now, in fact, a circus strongman really did exist. In April 1940 a German agent called Ernest Weber-Drohl landed in Southern Ireland, which was neutral during the Second World War, and he was captured by the Irish police and prosecuted in the Dublin district court for being a foreign agent. His defence was that he was a professional weightlifter who had appeared as ‘Atlas the Strong’ with a circus in Ireland before the war, and he had come back to Ireland to find his two illegitimate children.

And this was the kind of little news item which would have gone through to Britain because they were so worried about German spies in the Second World War. Ian Fleming was the personal assistant to the Director of Naval Intelligence at the time, and it seems to me almost inconceivable the item didn’t pass across his desk, because the co-incidence of writing about it in From Russia with Love is just too strong.

What do you think it is about Ian Fleming which so encapsulates the British Secret Service in the public’s view?

It’s the combination of the debonair skill of the English gentleman, and his light-footed ability to move through the highest levels of society without any kind of problems, with fantastic technical expertise, backed up with the most improbable gizmos of one sort or another. And although Bond gets wounded or into trouble, he always manages to come out on top in the end.

You have been doing some proper research into the British Secret Service: are the books complete fiction or do certain elements of this really exist?

It is not complete fiction. There was a man called Biffy Dunderdale whom Fleming knew and who was the MI6 Head of Station in Paris in the 1930s. He was a man of great sangfroid and style who liked fast cars and pretty women and was quite an important figure. He travelled under the name of John Green, and was a glamorous figure a bit like Bond. On the other hand, one of the reasons he was in the Service was because he spoke Russian like a native, as well as other languages, which was definitely something you needed – and still do – and something James Bond never seemed to be able to do.

And how do you think the Secret Service differs from something like the CIA?

They [the CIA] are just an enormously bigger organisation and have a lot more resources. They started from almost nothing in the Second World War. They are much better backed up in terms of technical back-up and resources. But they don’t operate in the same way as people like James Bond, who was a bit of a loner, relying on his native wit to get by. You do get some people like that on the American side but they don’t have that languid air of effortless superiority which certainly epitomises Bond and, by default, our perception of the Secret Service.

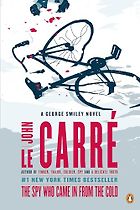

Let’s move on to your next book, which is about an iconic time in the history of the British Secret Service. This is The Spy Who Came in From the Cold by John le Carré.

This novel shows a very different kind of world and service. It is a grainy monochrome world with amoral spymasters moving pawns about the board in this grim Cold War era. These are gripping psychological novels as much as anything else. The novel has Smiley in it but the central figure is Alec Leamas, who is a hard-bitten veteran whose duty to the Service conflicts with his relationships and his humane side. He has to work in an amoral value-free world.

This is at the far end of the spectrum from James Bond, but it also says a lot about the bureaucracy of the Service. The decisions made back home in what le Carré calls ‘the Circus’ – head office – are really important and you don’t see so much of this in the James Bond books. Le Carré’s book is from a moment in history when you have this monolithic kind of Soviet enemy with the West defying it. And you have spymasters on each side who have perhaps more in common with each other than their own fellow countrymen. And there is a little bit of that, too, in the real story, I am sure.

Your final choice is Secret Service: The Making of the British Intelligence Community by Christopher Andrew.

I still go back to this book, which was published in 1985. It is a real pioneering wonderful book underpinned by proper academic scholarship. But it is also a great read. It is the sort of book I would have loved to have written myself and I perhaps tried to do it a bit with my recent book.

It also represents a time when Christopher Andrew didn’t have any inside privileged information as he does now [as official historian of MI5]. And it shows just how much you could do because he got it pretty well right, and we are talking about over 25 years ago now. He writes about how the Service built up from the ad hoc nature of the early days in 1909 right through the Second World War when MI5 and MI6 came of age. The book has a wonderful mixture of academic rigour and lightness of touch, which is the ideal of how you would want to write from your ivory tower.

How do you think he managed to get it right, given that he didn’t have access to all the information and archives that have come out recently?

I think professionalism, finding evidence from a range of different sources. And then he used them creatively but he didn’t make stuff up. Some journalists tend to populate their books with re-creations and imagine what it would have been like, which may or may not have happened. As historians we can’t do that. And Christopher Andrew has a core professionalism, which means he cannot and does not do that. He writes well enough not to have to do that.

November 1, 2018. Updated: March 16, 2024

Five Books aims to keep its book recommendations and interviews up to date. If you are the interviewee and would like to update your choice of books (or even just what you say about them) please email us at [email protected]

Five Books interviews are expensive to produce. If you've enjoyed this interview, please support us by donating a small amount.