For any readers, who are a little unclear on what ‘Afrofuturism’ encompasses, might you offer us a brief overview?

Afro-futurism is a vexed term for some Black people, because a white man—Mark Dery—came up with it. To me, Afro-futurisms is not just about the diaspora and all that nonsense. The Afro- prefix in any definition means relating to, out of, African. So this name, Afrofuturism, a borrowed name, is important if it denotes a subgenre of the futurist and fantastic depicting the black experience in the speculative arts.

How did you decide on these five books—what are you looking for in an Afrofuturist novel?

I feel things deeply and these are all books that are, to me, Kafka’s axe—they rouse me with a blow to the head!

The first book you’ve chosen to recommend is Womb City by Tlotlo Tsamaase, a 2024 debut. Would you introduce it to our readers?

Womb City is a highly imaginative complexity that spans across themes of human rights, belonging, artificial intelligence, male dominance, surveillance, crime and haunting in a futuristic world that is dystopian to the women who inhabit it, and utopian to its men.

There’s much death and life in Womb City, and it reminds us of the quintessential value of womanhood that society can take for granted. It is a magnificent story that’s fast paced and pregnant with so many twists.

Womb City is set in a dystopian Gabarone City, Botswana. Would you say Afrofuturism tends to focus on specific regions or cultures, or is it quite free-ranging?

I like to think of Afrofuturism as imagining a future Africa, wherever that may be, an application of storytelling to interrogate and position the self and identity through story.

Your own Mage of Fools, for example, is set in a socialist country called Mafinga, run by an all-powerful corporation called Ujamaa. I recognise Tanzania, but is it wrong to understand Afrofuturism so directly? How do you think about the link between your speculative fiction and real life, real countries?

It was very intentional that I chose Mafinga, a made-up country, in what is a real city in Tanzania. In Mage of Fools, I wanted to create a realistic dystopian futurism that fed on a largely pessimistic narrative that was technologically- and futuristically-influences.

It’s a cautionary story that explores bad leadership, social injustice and climate change to show how bad things can get if we can’t do better. I set out to write a novel with an urgent call to climate action, and with a strong female protagonist in a story of resilience. It imagines a future Africa in worst throes of climate collapse culminating in a desolate world of oppressed people, where only few people benefit from ‘ujamaa’—African socialism.

Let’s talk next about The Old Drift by Namwali Serpell, which begins in the 19th century and ends in the near future. It switches style or genre as it goes: magical realism, social realism, historical fiction—and, of course, Afrofuturism. Tell us more.

Namwali Serpell’s The Old Drift astounded me in both the monstrosity of the tome and how its fantasy and science fiction is so subtle, the book is passable as literary fiction. It’s an intelligent book that sweeps across class, colour, generations with its deception, reflection, fraud, prejudice, imbalance, balance, devotion and hope, in rebellious text that subverts the reader’s expectations with a comedic drama that’s integral to the story.

Serpell has said she used to joke she was writing “the great Zambian novel”. Then, she said, “at a certain point, I realized I actually did have a responsibility to explain Zambia and its history.” What do you think of that idea—that African writers, or writers of African descent, have some kind of literary responsibility?

I like to think of the author as an agent of change—we have a responsibility in the visibility we claim through our texts. With the writerly pen, we can be subversive activists, giving voice to the voiceless, as we scrutinise and shape our characters and their journeys in whichever themes.

Namwali Serpell explores ideology, supremacy, disease, curiosity in relationships forged and lost. She casts a spotlight on the place of women in society, on the intolerable choices of mothers and their children, on the quest for identity, a search for belonging. If this is literary responsibility, I say, Amen.

Can we discuss Black Apocalypse: Afrofuturism at the End of the World next? Tell us about it.

Tavia Nyong’o’s Black Apocalypse is a book I can’t stop talking about. Remember Kafka’s axe that shatters the frozen sea within us? The text in this book is wounding, stabbing, in its deconstruction of anti-black racism, Afro-pessimism and Black counter-speculation. The world needs, now more than ever, writers and readers who embrace prolific differentiation and survivalist self-invention in the speculative estrangement that Afrofuturism affords in an apocalyptic era. Fuck Trump.

How do you think of Afrofuturism in relation to other approaches? Does it nest inside science fiction? Or exist all on its own?

I hate to be a gate keeper and you may have heard some texts refer to me as the ‘queen of genre-bending.’ I love the playfulness of text, Roland Barthes’ revolutionary thinking in text as a discovery and a continuum in the pleasure of the text. Why constrain anything to a single genre? Afrofuturistic texts can be speculative—encompassing science fiction, fantasy, horror and their subgenres.

Did you ever consider that Afrofuturism can be more than text? And, as I wrote in Afro-Centered Futurisms in our Speculative Fiction, “embrace art, literature, architecture, music, even style from within Africa and the diaspora, where Afrocentric creatives identify with it and some—like me—embrace it in association with our works.”

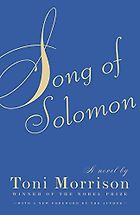

Next you’ve selected Song of Solomon by Toni Morrison. It’s set in the United States. Why do you recommend it in this context?

Readers don’t realise how speculative Toni Morrison’s Song of Solomon actually is. While set in the slavery days of the Deep South, this novel, like Morrison’s other novels, holds Black cultural focus. The essential aspect of its cast is their being Black, their battles with or acceptances of being Black, and the surreality of the text pinnacles at the end when protagonist Milkman flies, literally, speculatively, futuristically.

So I suppose I should take from this: cutting-edge technology is not necessary to reflect the Afrofuturist mode?

I would say it is limiting and myopic to confine Afrofuturism with “cutting-edge” technology. Afrofuturism, as I wrote in Afro-Centered Futurisms in our Speculative Fiction, is to reimagine Africa in all its diversity, to expand and extrapolate it through literature, music, the visual arts, religion, even philosophy, anyhow that haunts imagination and transmutes a craving for revolution.

I think that brings us to The Hundred Thousand Kingdoms by N.K. Jemison, an epic fantasy romance. How does it approach Afrofuturist themes?

N.K. Jemisin’s The Hundred Thousand Kingdoms is a cross-genre fiction that explores themes of cultural identify and what people deem the “quintessential” hero. I like that the story pours new wine into old skins, borrowing from the mythology of gods and mortals, and character stereotypes, for example the trickster Sieh, in a world of role reversal where the gods are enslaved.

As I wrote in another of my books, Writing Speculative Fiction, “in this first book of the Inheritance Trilogy, Jemisin borrows from a northern African tribe in designing the traditions of the fictional barbarian Darre—protagonist’ Yeine Darr’s people. Stealing from Christianity and concepts of resurrection, the Holy Trinity, as well as from Hinduism, Egyptian mythology, and Greek mythology, Jemisin hurls in the appeal of a demonic lover, forging a romantic plot as fundamental to the speculative work.

You are the co-editor of Sauúti Terrors, the second anthology in the ‘Sauútiverse’. What was your aim with the collection?

Simple, really. We wanted to give voice to writers from Africa and the diaspora to shape the futurisms in their stories, while paying attention to some of Africa’s problems, such as famine, gender and sex discrimination, climate change, atrocious leadership, and more, to reshape the narrative in cautionary or hopeful ways.

The invitations to writers outside the Sauútiverse Collective was targeted. The main challenge was to see how authors external to the foundations of the Sauútiverse could interpret our story bible and come with their own unique, original texts that explored and expanded our world. Looking at Sauúti Terrors, I think they succeeded rather well.

Did the process of putting it together leave you feeling optimistic about Afrofuturist writing today?

Completely! I’ve never felt more exhilarated about Afrocentric writing, creative works by Afro-descendant peoples sharing their longings—past, present and future—through storytelling. We’re excited about promoting this significant anthology in a UK book tour, running from the end of January to mid-February, 2026.

Interview by Cal Flyn, Deputy Editor

January 2, 2026. Updated: January 4, 2026

Five Books aims to keep its book recommendations and interviews up to date. If you are the interviewee and would like to update your choice of books (or even just what you say about them) please email us at [email protected]

Five Books interviews are expensive to produce. If you've enjoyed this interview, please support us by donating a small amount.