You’ve described your latest novel, Heart the Lover, as “a big fat love story.” That made me very happy. Because, I think, literary writers often veer away from romance and love. Would you agree?

That’s interesting. I think there are a lot of pitfalls, and reasons to avoid it, but I have to say that all the literary novels that I really love have some form or some hint of a love story in them. It’s such a natural human emotion that it’s hard not to write about it, in my opinion, and I’m definitely attracted to those stories in literary fiction.

What do you look for in a literary love story?

I think there needs to be a sense that the characters belong together. To have that sense, we have to know the characters. We have to feel they are flesh and blood, people that we know and that we could find on the street. Then, when they meet each other, the dialogue is so important. I love humour, I love banter, and that’s definitely a way I connect with people, and how I like characters to connect. If there’s no humour, it doesn’t really work for me.

I guess there are exceptions to that rule. But I like that: banter, a connection, then the emotion can follow after that. Then there needs to be the sense that they are missing each other, and that when they come together they are both better for it. I want to feel that sense of: they need to be together.

For me, many of the foundational literary love stories are by Jane Austen, who is the author of the first book you’ve chosen to recommend. After considering several of her texts, you’ve settled on Persuasion. Could you introduce it to our readers, in case they don’t know it well, and explain why you enjoy it so much?

I’m really interested in a love that starts in the past, or at the start of the book, and then we track it. Persuasion is wonderful in that sense: we meet Anne Elliott when she is 27 years old, having had this big love eight years before.

Yes, she broke off her engagement to a young naval officer.

She was persuaded by her dead mother’s best friend not to marry him: he wasn’t quite up to snuff, he wasn’t of her class and education, that sort of thing. She was young, she let herself be persuaded.

Eight years later, her family are having money troubles. They’ve rented out their house. They are land rich, but everything-else poor. Her father is a vain, narcissistic character. Anne and her sister move back into the neighbourhood, and she encountered Wentworth again after eight years. It’s clear straight away that she still has the exact same feelings for him, but she has no idea about how he feels, although she suspects that he hates her. It starts there.

I really love this book. It’s one of her later books—the last novel she published before she died. It’s very interior. There’s an interior voice working in a way that she didn’t have in her other books. And so it feels emotionally very satisfying. We know what they are both feeling, and it’s a powerful attraction that works on all levels.

Choosing the right or the best partner seems to be the central preoccupation of Austen’s work.

I think that’s very true. You know, in Austen’s time, that was the female preoccupation. Her destiny depended on it. There was no employment to be had, no possibility of self-sufficiency. That was it, so if you wanted to have food and to have children, and to be able to feed those children, falling in love with a very poor man was an extraordinary risk.

You have to understand the kind of pressures that were on them: they had to find someone to provide for them, because they could not provide for themselves. I mean, there were governesses and teachers—there were a few options. But that choice was all-encompassing, and probably more important than maybe it is for us today.

Perhaps we see some similar pressures on the protagonist of your next book recommendation, Thomas Hardy’s Tess of the d’Urbervilles. I was surprised that you think of it as a literary love story, because I remember it as a tragedy! Could you talk us through that?

One of my favourite sections of any book in literature is the part where Tess goes to work on the dairy farm and meets Angel Claire. She’s just had such a hard, hard time, and then she has this experience of being provided for and taken care of by kind people. For once in her life, she’s safe and secure. Happiness suddenly happens to her, and it’s so unexpected.

Then there’s Angel. She falls so in love with him, and he with her, and it’s so tender. I mean, when he saves her as the last person to carry across the little creek that’s overflowing on their way to church? It’s just beautiful.

I know Angel has his issues, but Hardy is also using him to demonstrate society, cultural mores. He’s incapable for a long time to forego his religion and his society to be with her, and to accept her past. And I find it so moving and poignant—and a kind of lesson to us all, at any age. I think we all stumble into these situations when our heart, our emotion, our impulses, don’t match what people and society expect of us.

The next book you’ve chosen to recommend is Brooklyn by Colm Tóibín. Could you introduce it to our readers?

Well, maybe not too many people will need an introduction, because it’s been a very popular book and a really beautiful movie, which I don’t normally say about most book adaptations.

In Brooklyn, we have Eilis Lacey, who comes from Ireland to Brooklyn, where she meets Tony—a plumber with a big Italian family. I don’t want to give too much away, but she’s already very attached to Tony, but then—after maybe nine months or a year—she has to go back because her sister has died, and there she meets Jim. They have the summer together, then she, very abruptly and without saying goodbye, leaves and goes back to her life in Brooklyn.

The love story is the motor to the book, although you take away so much more from the book than a simple love story. It’s really a book about emigration and immigration, and feeling dislocated both from where you came from and where you landed.

“All the literary novels that I really love have some form of a love story in them”

And what do I love about it? Well, just that Tóibín’s writing is beautiful. I love every single one of his books. I’m completely enamoured with his writing.

Then, there’s a sequel—which Colm Tóibín wrote years later—called Long Island. On the first page, a stranger comes to the door saying that his wife is pregnant with Tony’s child. So she goes back to Ireland, where she sees Jim again, and that plays out all over again in a different way. Of course, many years have gone by, more than have passed for us waiting for the next book. Jim has never married, but he has his own resentments and feelings.

Tóibín investigates that relationship again when they are very different people, and yet similar. Old qualities come out in them that were maybe forgotten. I love that intersection of love and time. I think that’s pretty much my whole focus, as a writer.

Absolutely. It does seem like there are parallels with your novel Heart the Lover here. You have lovers from the past reappearing in the present. Old dynamics playing out in new ways. Perhaps you’d speak to that?

Yes, the first section takes place in college. There are three people, two love affairs. Then we take two leaps in time. So many things have to be investigated and worked out 30 years later. I’m just really interested in those early attachments and the huge mark they make on you, even if it doesn’t turn into a lifetime together. The reverberations are always there, and occasionally there can be fresh interaction and fresh developments in the relationship. I find that all fascinating. What life and time does to a psyche, and to a heart, is really intriguing to me.

Relationships can have very long half-lives.

Exactly, yes.

Shall we talk about Man Gone Down? It won the International Dublin Literary Award back in 2009. The author, Michael Thomas, is very interesting; I read a profile of him recently in the New York Times. Tell us about his debut novel.

It’s a story of a black man in New York City, who is married to a white woman. They have three kids together. It takes place over the course of four days while he is in utter crisis trying to save his family. The love story is really the love of one man trying to keep his family together, when every single force that could be working against him is working against him.

He has four days to earn over $12,000 to pay for his children’s tuition, find an apartment, and move his family home from where they have been ensconced for the summer—kind of in limbo with his wealthy mother-in-law, who has a very strong personality and is very interested in protecting her daughter and her grandchildren.

This man doesn’t have a name in the book. He’s so hard and vulnerable and frantic. He’s desperately in love with his wife and his children. It’s just an incredibly high octane series of crazy situations with him trying to hustle and to work as much as he can and figure it out. This is all driven by love, which is why I wanted it on this list. It’s not in pursuit of love; it’s him trying to hold on to what he has.

So often we see the unrequited or pre-requited beginnings of a relationship in fiction. But those later stages of a great love? I feel they have a lot of potential too.

Yes, and it’s the great majority of the time that we spend with the people we love. It’s not the beginning, it’s all the rest of it. And I feel that does get neglected.

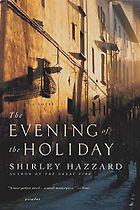

Let’s move onto your final book recommendation. This is Shirley Hazzard’s The Evening of the Holiday, which is set in the Italian countryside. Perhaps you’d tell us more.

This is a book that I read over and over. I keep it on my desk when I write, because I feel like I can turn to any page of that book and remember what good writing is and why I write.

It’s the story of Sophie. She lives in England, but we find out she’s half Italian. She goes to see her Aunt Luisa just outside Siena. She goes to a sad little afternoon tea, with Luisa’s friends, who are artists and they are older. Sophie must be early thirties, and there she meets the middle-aged Tancredi, who is not really in the mood to be there, and doesn’t much like the look of her.

So it starts slowly, and I think reluctantly, on both of their sides. But the minute they start speaking to each other, they have this wonderful, literature-fueled conversation that carries through the rest of the book. It’s beautiful writing. Every sentence is so stunning. Everything in it just moves me. And so their love really moves me.

Sometimes I recommend this book, and a lot of people don’t feel it the way I feel it. Theirs is a love that is definitely never going to work. They live in different countries. There’s a lot of mystery there. It’s hardly ever mentioned, but we don’t know what attaches her to England. She writes a postcard that says something like, ‘I miss you all.’ Does she have a husband? Children? We have no idea. But she can’t stay, and he’s married, although they don’t see each other very much. It’s poignant from the beginning because of that, and it’s just a beautiful moment in time when two people who are lonely and a little bit lost find each other and give each other something. Then it has a really spectacular ending—such a beautiful, moving moment that takes place about six months later.

Perhaps that leads us back again to what you said at the beginning about capturing a chemistry on the page. A sense that, despite all complications, there might still be a true connection between characters that can be somehow bottled.

That’s so true.

And I think you wanted to give a special mention to a Shirley Hazzard short story, ‘Vittorio.’ It’s available to read online in The New Yorker archives.

I just love ‘Vittorio’ too. I couldn’t decide which love story was more powerful for me out of the two Shirley Hazzard choices. ‘Vittorio’ is not a very long story. It’s about an English couple who come to stay at an older Italian man’s house. He has an extra room that he’s letting. He’s an old professor, very proper. And she’s a young, unhappy wife, married to a pompous, awful man. Or—he’s maybe not so awful, but she’s not happy with him, and he’s dry and remote.

Vittorio lost his wife a while ago, and I think he’s been feeling a little dead inside. And this woman brings him to life. Nothing ever happens, but she becomes aware of it, and it’s a simple story about a man starting to feel again after a great hurt. I find it so lovely.

I also just love being in Italy, even in books. So that has something to do with it too—all the Italian details and food and streets… just very thrilling. Hazzard lived in Italy for a long time and she was as enamoured with it as I am. You feel that in every sentence. So there is her love of Italy in that story as well.

Perhaps to close our discussion, I can ask you something about endings. We ran an interview on Thomas Hardy’s best books recently, in which I learned that Hardy had been, essentially, ordered by his editor to add a happy ending to Far From the Madding Crowd. And he did, although somewhat reluctantly. What are your feelings about happy endings, or the expectation of resolution?

That’s interesting. If I look at this list, there aren’t many with happy endings. I don’t know what is so satisfying about a tragic ending, or an ending that isn’t an ending. I think that can be moving in its own way. I absolutely don’t need them to end up together, and it’s a harder route to navigate. A happy ending in a literary novel? It’s a real challenge. So it’s definitely not a requirement for me. I love the happy tears I might shed at a happy ending, but there’s also something very, very moving about it not working out.

Interview by Cal Flyn, Deputy Editor

October 7, 2025. Updated: October 31, 2025

Five Books aims to keep its book recommendations and interviews up to date. If you are the interviewee and would like to update your choice of books (or even just what you say about them) please email us at [email protected]

Five Books interviews are expensive to produce. If you've enjoyed this interview, please support us by donating a small amount.