Here we are in Riga at a festival celebrating the centenary of Isaiah Berlin – possibly the greatest public intellectual of the 20th century, a Jew and a liberal who believed firmly in the two state solution. You’ve chosen five books about the Palestinian-Israeli conflict, none of which are by Berlin. Is there any particular rhyme or reason to your selection?

Obviously there are a lot of books about the conflict, and I’ve read only a fraction. But I’ve picked out the ones which are not even necessarily the best of that fraction. Just the books that for one reason or another have made an impact on me because they were useful in helping me get at something deeper at the time when I read them, something about opening up my understanding to other people’s point of view. Which, when I think of it, is a very Berlinesque attitude. He believed in pluralism. He believed that is was possible to comprehend someone else’s values and consider them to be objective and valid even if you fundamentally disagreed with them.

So this is a selection which helped to determine the way in which you framed your own writing, and I notice that with one exception, they are all books written from a personal point of view. Scars of War is the only self-consciously scholarly book. The rest are memoirs and novels, beginning with The Yellow Wind by David Grossman. What is a yellow wind?

In the original Hebrew edition it was called The Yellow Time and I don’t remember what that refers to. But in the English version Grossman recounts a conversation with a Palestinian farmer who tells him this legend about a ‘yellow wind’ that comes from the Gates of Hell, and seeks out people who have performed ‘cruel and unjust deeds’ and destroys them. The implication is that Israel has to watch out. That there is something that’s going to come along and destroy it. David Grossman was writing in the context of the First Intifada which broke out in 1987 and took the Israelis completely by surprise, because the Israelis had permitted themselves this myth that the Palestinians were actually much better off under Israeli occupation than they had been under Egyptian or Jordanian occupation. Which wasn’t entirely a myth. There was a lot of truth in it – the economic conditions improved, the human rights abuses were far fewer under the Israeli army than under the Egyptian or Jordanian armies. And so the Israeli narrative was: ‘Oh, so the Palestinians are probably grateful to us.’ It didn’t really occur to them that at some point there would be a Palestinian rebellion against them; and in fact even the Palestinian leadership, the Fatah leaders – Yasser Arafat’s people – did not anticipate it. They didn’t realise that there was this unrest brewing amongst the Palestinian people. And so suddenly when this uprising broke out in 1987 it took everybody by surprise.

How was it that Yasser Arafat, who we think of as the most significant militant leader of the Palestinian cause in recent times, did not foresee the rebellion?

Well, he himself was at that time in exile. He and the leadership of the Palestinian Liberation Organisation (PLO) were all outside, in Lebanon, then Tunisia. So they were all sitting in Tunis at this point. There was a local leadership of people that were loyal to them on the ground, but I don’t think they were very much in touch with it either. They didn’t really notice what was going on. The people who did manage to grasp it – who did manage to turn it to their political advantage – were a group of Islamists who formed Hamas, essentially on the back of the uprising, and managed to claim credit for the operation even though they were not really the people who started it. And so that was what started off this whole, very deep division within Palestinian society that exists today between Hamas and Fatah.

So where is David Grossman coming from?

Grossman had been an Israeli left-wing activist since the occupation. He’d been against the occupation and he’d written about that, and then when the Palestinian uprising happened he realised that he, like the rest of the Israelis, didn’t really understand what was going on there, and so he resolved to go and spend some time amongst the Palestinians talking to them.

So what made this book significant for me was that I actually read it many years before I started my stint in Jerusalem for the Economist. It’s the only book on this list that I read before I started the job. I read it, I think, around the time that the Second Intifada began in 2000, and I began my job in 2005. The point is that I’d been to Israel a lot, but I’d never really tried to understand the conflict from a more neutral point of view.

What was your view?

I don’t know. I didn’t really know enough to have a view. I believed in the two-state solution because that was the kind of thing that one believed in. I believed in the sorts of things my circle believed in.

And what was your circle?

North London, liberalish, intellectualish, Jewish – but I had no informed point of view, so reading Grossman gave me two things. One was that it was the first time I’d really read anything about the Palestinians. The second was that I hadn’t been working for very long as a journalist, and what he demonstrated to me was a capacity to write with empathy about an ‘other’ – somebody who you don’t identify with. In other words, what struck me at the time was that you could let a Palestinian farmer speak and Grossman would record his words and reproduce them and you didn’t feel any sense of intervention by the author, or of any refraction through his lens. He was very good at putting across what those people were saying and letting that speak for itself, and it struck me very powerfully that that was what a journalist should do. Which was actually very hard to achieve in practice because the Economist is not about individual people; not about long quotes or interviews. It’s much more about analysis, about refracting things through your own point of view. So I didn’t get to practise that sort of thing a lot, but nonetheless it was always there in the background, that this was what the aim should be. One should at least put across the views of the people you’re interviewing so that the reader can assess them.

Your second book is Cain’s Field: Faith, Fratricide and Fear in the Middle East by Matt Rees. Again a book from the point of view of individual lives, and in this case emphasising how both sides have frequently turned on their own people in order to preserve their particular definition of the conflict.

Exactly right. Matt Rees is now a friend of mine, but I read the book before we were friends. What struck me about it was, in many ways, what struck me about The Yellow Wind. He tells a series of stories, some about Israelis, some about Palestinians, and again he is very good at letting the characters speak. The style is a kind of ‘new journalism’ style, so he writes this narrative in which he makes you think that he actually knows the inner thoughts of his characters at every stage, and that’s a tricky one to pull off. He does it very well, but more to the point he lets you completely empathise with each of the figures, whether it’s a Hamas militant or whether it’s an Israeli settler. In this case the Hamas militant is fighting against other Palestinian security people who have killed members of his family, and the Israeli settler has lost his son to Palestinians, but is also in a very difficult dynamic with other Israelis. The main point is that Rees is not telling stories so much about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, as about the internal divisions on either side of the conflict. So on the Palestinian side it’s about this fight between Hamas and Fatah, between the militants and the security services. And on the Israeli side it’s about, for instance, the divisions between the religious and the secular, or about the rapid development of the Israeli cultural identity. There’s a great piece in it about the treatment of Holocaust survivors in a psychiatric institution in Tel Aviv, and about how Israel, which was founded as the country that was meant to be the refuge of people from the Holocaust, actually treated a lot of its own survivors incredibly badly.

Does he give a reason for that?

He does. The background that he gives to it – and this is a fairly common understanding now in Israel – is that the early Zionists who set up the state came with this ethos of being fighters, of being tough. And there was a perception which took a long time to shake historically, that the Jews in Europe had not put up a fight, and that they had gone like lambs to the slaughter. So for a long time there was something almost shameful for Israel about its Holocaust survivors – about the fact that they were the remnants of a people who had allowed themselves to be slaughtered. Also in Israel, as in the rest of the world, it took quite a long time for the stories of the Holocaust actually to be told, and it wasn’t until the Eichmann trial in 1962 that people began to understand what it was actually like in the camps. What life was like for the survivors. Until then they’d been swept under the rug.

Was this the time when Israel began to appropriate the political value of the Holocaust for itself? The idea of Israel as a nation of people which should not be persecuted in any way because the Jews had already been the victims of the greatest crime of the 20th century? The crime which in many ways defined the modern notion of genocide?

I don’t know exactly when that began to happen. I couldn’t tell you for sure, you’d have to talk to an Israeli historian about that.

Well, that’s obviously hugely controversial. Rees is introducing a difference between individual experience and the way that a more total community is formed politically and showing that the casualties of that political identity are the people who really should benefit from it.

Right. He’s showing how the divisions or dividing lines within society, the things that make it difficult for progress between these two societies – the Israelis and the Palestinians – are often internal clashes. I read this book, as I told you, at the beginning of my stint, and the more I stayed there the more I thought that that was true. If I look at the situation now there, the reason why I think that there is no progress on the peace process is very much because of internal divisions on each side that make it very difficult for a leader to actually progress.

So is there any mirror between these internal conflicts?

There is and there isn’t. Each society is very different, very sui generis. There are ways in which they are the same, because there is a religious versus secular conflict in each society, for example. And there is a certain amount – though much less so – of a social stratification that divides them. So on the Palestinian side there is the gap between the refugees and the non-refugees, and each of those two groups has rather different expectations and desires in terms of what they want from a solution. And on the Israeli side there are the divisions between the settlers and non-settlers…

I suppose the point that Rees is making is that the internal differences within these two societies are worth rescuing from the generalisations that usually come to mind when we talk about Israel and Palestine.

Yes. There are a lot of books you can read that are an attempt to paint a complete picture, and I haven’t picked any of those except for one. Which we’ll come to next. Those sorts of books are very good for getting an overview of what’s going on, but none of them stuck with me because I didn’t feel they revealed anything of a deeper truth. A book like Rees’s does. It lets you touch something you don’t ordinarily get to put your finger on.

Let’s talk now about Shlomo Ben-Ami’s Scars of War, which appears to undertake the extraordinarily ambitious task of representing this conflict in a scholarly, historic way, equally from every point of view.

Well it’s written from a very Israeli point of view. The writer is Shlomo Ben-Ami, who’s a liberal, who’s an intellectual, who’s a historian. But he was also the foreign minister for a year in 2000 under Barak. There are quite a lot of books by historians and journalists that try to be neutral and objective. And then there are books by important figures in Israeli society and politics, who will obviously tell the story through a lens of who they are and what they did. But I don’t know any books apart from The Scars of War which are by both a professional historian and a participant – at least from the Israeli point of view. Ben-Ami tries to keep a detached perspective and brings his personal experience in only when it’s relevant. So, for example, he was involved in the Camp David negotiations, and he does an interesting job of debunking the myth which is still widely believed in Israel that the Israelis made Arafat a marvellous offer which he turned down flat.

The Palestinians never miss an opportunity to miss an opportunity?

That was a famous quote by one of Ben-Ami’s predecessors as foreign minister. And if you asked Ben-Ami, he would probably agree with that statement in general terms, because it’s very true that the Palestinians have missed a lot of opportunities. Then again so have the Israelis. Ben-Ami says that what happened at Camp David was not just Arafat’s fault. But more generally he shows how Israeli policy is founded on this idea of a struggle for its survival, and that at the beginning the occupation of the West Bank and Gaza seemed to make sense from the point of view of this strategy. But it stopped making sense. So he goes back to 1967 when the Israelis had captured all this territory and felt like it was on top of the world, and then there was the question, ‘What should we do with all these territories?’ And Ben-Ami recounts the episode of four men from Mossad who did some research and said, ‘If we hold on to this land it’s going to turn into an albatross around our necks. The Palestinians are interested in negotiating independence and we should negotiate with them. We should give Gaza and the West Bank to the Palestinians and let them set up a state right now.’ Well, there was some initial interest from the Israeli cabinet in this solution, but within a few weeks, for a number of different reasons, that interest faded and the notion that these territories were of strategic value took hold. And that was it.

So Ben-Ami’s book is an interesting book, not because he is pretending to be some sort of noble gas that does not react to anything, but because it’s a courageous attempt at a scholarly history by a man who was also a player. Hopeful stuff.

Yes, it makes you realise that Israel really does have some great people in it. Unfortunately, they tend not to have too much influence these days. But it’s interesting for that intellectual honesty.

Your fourth book is a novel first published in 1949, a year after the declaration of Israeli independence and the 1948 Israel-Arab war.

Khirbet Khizeh by S Yizhar and the final book on the list both come from the same people, and I’ll explain why in a bit. Khirbet Khizeh is an interesting book because it’s a very, very short novel – a long short story really – written by this guy who was an intelligence officer in the fledgling Israeli army. The book’s told from the point of view of a soldier in this army just after the Israeli war of independence, as the Israelis call it, has finished. And he and his squad have been detailed to go and ethnically cleanse a Palestinian village which has remained inside Israeli territory. He tells how they’re wandering around on this lovely day and the sun is shining and it’s idyllic. And they go into this village, round up the Palestinians and put them on trucks and send them away to the border to the West Bank, where Jordan is in control. The book’s beautiful because it makes a gradual transition from this bucolic setting to these increasingly menacing events. The narrator begins to realise that there’s an uncomfortable parallel between what’s happening here and what was being done to the Jews in Europe. He turns to one of his fellow soldiers and says this, and the answer he gets is: ‘Do you know how badly these people would be treated anywhere else? We’re doing them a favour. We’re putting them on trucks and we’re sending them to their own people. No other army in the world would treat them as well as this.’ That kind of dialectic has been a relatively constant theme of the whole debate in Israel right up to now. There’s a camp that says we’re doing bad things and there’s a camp that says that anybody in a similar position, surrounded by enemies, threatened with extinction, would behave much worse.

How was the book initially received in Israel?

What makes Khirbet Khizeh particularly interesting is that it was published in Hebrew in Israel and was very widely read, and is still, I think, on the school curriculum. So the story of the ethnic cleansing of Palestinians is still very much part of Israel’s literary history. But in spite of all this, it did not enter the national consciousness. In other words it was very much a national myth until not very long ago that all the Arabs left Israel of their own accord, because the Jordanians and the Egyptians and the Syrians and all the rest said, ‘Come to us and we’ll all repel the Zionist aggressor together.’ The reality was that some people left because they were scared and some because they were expelled. And there were some massacres as well. So this book was very widely read, and yet somehow its story was not part of the national story. It came out again in translation very recently and was published by this small boutique publishing house in Jerusalem. It’s a publishing house that specialises in translating Levantine literature and bringing it to the attention of English speakers. It’s run by a couple and the wife in this couple, Adina Hoffman, wrote the fifth and final book on my list.

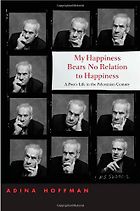

My Happiness Bears No Relation to Happiness.

Yes. She and her husband also translated this Palestinian poet called Taha Muhammad Ali. He was relatively unknown, and they became so enchanted with him that she decided to write his biography as well, which is this book. It’s a story of the Palestinian people told through a man who actually remained within Israel after the war of independence. And that’s interesting because most of what you hear about the Palestinians is from the Palestinians who left. The Palestinians who remained inside were a shameful subject to other Palestinians for quite a while. They were seen as the collaborators, the quislings. They got Israeli passports, they became part of the Zionist identity, and to this day they are a little distrusted both by other Palestinians and a lot of the rest of the Arabs.

So they really get it coming and going?

Absolutely. So his story is interesting partly because of that, and partly because the book is also, tangentially, about Palestinian poetry. And even for somebody who knows nothing about poetry in general, and certainly nothing about Arab poetry, it’s interesting because it shows how these supposedly fallen, corrupted, marginalised Israeli-Palestinians were in fact the main fount of Palestinian poetry in the 20th century.

Because of their homesickness?

The book offers a couple of reasons. One is that under the British mandate, and then under the Israelis, Arab literacy in Palestine increased dramatically. The British were very dogmatic about having everybody in school, and the Israelis were keen on that too. However, the Palestinians living in Israel were very limited in terms of their political expression. There was martial law in Arab areas of Israel until 1966. And so one of the few ways in which expression was possible was through literature. Then in 1967, after Israel captured the West Bank and Gaza strip, the rest of the Arab world finally got back in touch with the Palestinians inside Israel and discovered this incredibly powerful and vibrant literary scene. So after 1967 the nationalist Palestinian poets inside Israel, who had never been heard of before, were lionised…

Incredible. And was Taha Muhammad Ali one of them?

He knows them all. He’s present on the literary scene, but he doesn’t write. He’s a shopkeeper. He owns a souvenir shop in Nazareth. And it’s only after quite a while knowing all these other literary figures and being involved in one way or another that he begins to write poetry. He writes his first poem when he’s 40. He publishes his first collection of poems when he’s in his 50s. But when this couple in Jerusalem discovered him and started translating him he started to become a sensation because his poetry was different from the rest. It wasn’t overtly political. It was political in a much more subtle way, and sometimes not at all: social or very personal. But there was also something about him personally, charming, rather bumbling – you know, a nice old granddad.

So very unthreatening. But what is his poetry resonating with in the experience of other Palestinian-Israelis?

It’s not in your face. It’s very subtle and gentle as I said. And yet it does penetrate into the very deep issues in this roundabout way. So it’s as if he’s saying, ‘Yes I’m a Palestinian, yes I’ve suffered, but I’m not going to make a big song and dance about it. Here are just a couple of things you should know…’ It’s that sort of poetry. He does it with a great deal of humour.

So it’s not a call to arms. It’s a marvellous title – My Happiness Bears No Relation to Happiness – what does it mean?

That’s the title of one of his poems, which is directed at attackers who are not identified. The poem’s saying, ‘You think you can do this, that or the other to take away my happiness, but you’re wrong, because my happiness is not what you imagine happiness to be.’

June 11, 2009. Updated: April 18, 2025

Five Books aims to keep its book recommendations and interviews up to date. If you are the interviewee and would like to update your choice of books (or even just what you say about them) please email us at [email protected]

Five Books interviews are expensive to produce. If you've enjoyed this interview, please support us by donating a small amount.