Tell me about the unifying theme of your choices.

The unifying theme is the balance between power and ideas. You need both. If you have power without ideas you can hollow yourself out, be self-erasing, and if you’ve got ideas without power then the ideas become irrelevant. It is a betrayal really of the ideas themselves. You need a balance between the two.

Who has that balance? Obama?

I would say Obama has that balance beautifully, and the inspirational thing about him is that he sticks to both his purpose and his strategy. He does seem to take damaging hits for the sake of his ideas. Amartya Sen also has that balance. He has ideas and he has his own picture of the world. One of his most compelling ideas is that no democratic country has ever had a famine. It’s one of those frame-changing findings.

The Idea of Justice is a magical book, not just because of the unbelievable depth and breadth of everything he’s read, but also because of his generosity of spirit. He argues with people at their absolute best, expressing their ideas often better than they had formed them themselves and then disagreeing with them in a way that makes them think: ‘I got that wrong pretty well, actually.’

The book’s central idea is the importance of what he calls capability but I would call power, and that it is not just about money. In the past, the centre left has got lost in the cul-de-sac of this definition of equality being about money. Sen’s example disproving that is that of a disabled person who will need more money because of his disability. Power is about the ability to make decisions and choices in your life, about capability.

He is brilliantly withering about democracy being a Western value, citing the example of Indian leaders Ashoka (304-232BC) and Akbar (1542-1605). The ancient history of democracy, he says, has even deeper roots in India than in Greece. This is about democracy as discussion as much as democracy at election. He uses that example to talk about world democracy. There is not going to be global democracy of government for a long time, but we’ve already got democracy of discussion with the internet, NGOs.

Who is Sen arguing with?

[20th-century American philosopher] John Rawls, mainly, with whom he taught a course at Harvard and to whom the book is dedicated. Sen thinks that American egalitarian liberalism was important in starting the debate but that it has significant errors at its heart. The first is that Rawls believed that justice was about perfect institutions, but it’s not. It is more practical than that. It is about how you can achieve a better world. You don’t need to know what the perfect world would be like in order to choose between alternatives. The second is the point I have already made, which is that justice is not about resources but about capability, power. There is the Hobbesian theory of political philosophy that is contractarian [that civil society is based on a contract between state and citizen] and there is the Adam Smith and John Stuart Mill theory that is comparative – you compare two moral options. Sen believes that this is superior to Hobbesian theory.

The Maurice Glasman, Unnecessary Suffering.

Glasman is the perfect person for Sen to be having a conversation with. Maurice would argue that liberalism, as expressed by people like Rawls, has a huge amount to teach us, but starts from the wrong place – from individuals rather than from relationships. He would argue that almost all of what matters in life is about relationships – family, love, culture, community, place. Written in 1996, the book is proleptic about what it might see as New Labour’s tendency to welcome change at any price. The book draws inspiration from Karl Polanyi’s The Great Transformation which said that the greatest cause of suffering is change that we can’t control.

This is a beautiful book, a human book. There is suffering we can’t avoid, like death and love, but there is also suffering we can avoid like unemployment and famine, and that the responsibility of politics is to protect us from such unnecessary suffering.

How? It sounds easy to say.

Well, Glasman is very involved with London Citizens, which is a branch of Obama’s community organising, based on the ideas of Saul Alinsky. Alinsky wrote a book that would have been my sixth book – perhaps I will sneak it in here. It’s called Rules for Radicals, and Alinsky was the original community organiser, who felt that the 1960s American student radicals made a lot of noise but didn’t achieve much change. This community organising was what Obama did in Chicago – organising ordinary people into a common purpose and a common effort so that they cannot be ignored, for example getting the housing organisation to admit to asbestos poisoning. The other big community organiser is Marshall Ganz, who is a lecturer in public policy at Harvard and was in there when Bobby Kennedy was shot. He was very influential in the Obama campaign.

The idea of the Glasman book then is that government should be able to run the state without the state becoming dominant. Market and states can both bully people, as can society (think about the Deep South in the 50s, for example). They all need to be strong to keep each other in check.

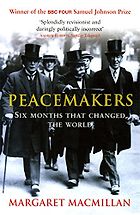

Margaret Macmillan, Peacemakers.

This is the best shortcut to the history of the 20th century. She focuses on the meeting between Lloyd George, Georges Clemenceau and Woodrow Wilson that decided what the new boundaries would be for the world at Versailles in 1919. On one level it is a great human drama, with Italy popping in and out depending on the state of its government, the origins of the conflict between Greece and Turkey and the Iraq war. That is all the fault of a woman who was a bit in love with Lawrence of Arabia and insisted on creating this country, Iraq. Rupert Murdoch’s father makes an appearance and what has happened in Palestine has its roots here too. Everything for right or wrong in the 20th century, the League of Nations and then the UN…all started here.

The book is a soap opera as well as a history book. It has these three central characters as well as all these mad folkloric characters from Greece, Turkey, Australia, South Africa, and it all took place in such a short space of time. This event was the transition from the British Empire to the American Empire.

R H Tawney, The Attack and Other Papers.

The Attack is worth reading just because Tawney is such an amazing writer and uses words better than anyone in British politics that I know of. But I also love this book because it makes the case that an important part of the Labour tradition doesn’t start with the state, but with individuals and communities and the way we build our lives together. Tawney is a good complement to Sen, actually. There is an essay written in 1944 called ‘We Need Freedom’ in which he is trying to persuade Conservative Britain not to worry about a Labour government. He argues that only Labour can provide real freedom because freedom is meaningless if it is just that nobody is going to stop you dining at the Ritz when you can’t afford it anyway. Freedom is the ability to dine at the Ritz.

Your last book, Robert A Caro on Lyndon Johnson. This is this unfinished four-volume life’s work?

Yes. Perhaps it’s only for the true believers. It is quite an enterprise to read, but compelling partly because Lyndon Johnson was such a beautifully unattractive character. He was a horrible bully who humiliated his staff and who found a way of endearing himself to the oil barons of Texas by launching a McCarthyite campaign, before McCarthy, against the electricity regulator. He ruined this guy’s life by accusing him of being a communist when he was nothing of the sort. So, on the one hand he was an ogre, but on the other hand he was the first person to get any civil rights legislation through the senate since the Civil War. The question is: do the ends justify the means? In his case the means were unspeakable but until Lyndon Johnson the Southern Democrats (some of whom were white supremacists) used the filibuster to stop any civil rights legislation getting through. He convinced them that he was on their side.

Do the ends justify the means?

I don’t particularly think so. I ended up not admiring him even though this book is an attempt to rehabilitate him. He left office completely discredited after his part in the Vietnam War. Caro has him as the Bevan and Attlee of America, but his means were unspeakable and he would never get away with it now. He wouldn’t survive a week in modern politics. This goes back to Marshall Ganz and Bobby Kennedy – Kennedy was, like Obama, campaigning for something he really believed in and when he was shot it broke the hearts of the American left and they have only really got the belief back now with Obama.

May 4, 2010. Updated: November 3, 2023

Five Books aims to keep its book recommendations and interviews up to date. If you are the interviewee and would like to update your choice of books (or even just what you say about them) please email us at [email protected]

Five Books interviews are expensive to produce. If you've enjoyed this interview, please support us by donating a small amount.