Talk to me about The Odessa File.

Now, Odessa File is Freddie’s second book (I always call him Freddie), and after the enormous success of Day of the Jackal he was thinking of doing something about mercenaries in Africa. His publishers said: ‘Do Nazis first and mercenaries later.’ That’s publishing pretty much to a T. Freddie had been Reuters correspondent in Germany and was aware that there was a significant number of former Nazis ending up in government and Simon Wiesenthal told him about Odessa. So he ended up with two men in mind – his real villain, Edward Roschmann, the Butcher of Riga, and the hero of his book, Peter Miller, who hunts Roschmann for reasons that become apparent at the end – there might be people who haven’t read this book. I read it as a teenager and loved it.

Is it a true story?

Ah, well, the problem with Odessa, which stands for Organisation of Former SS Associates, you can look the German up, is that if you’d been in the SS and were trying not to get hunted you’re not going to call your organisation that, are you? So, basically, it’s bollocks. I’ve spoken to Freddie and he all but admitted it, but because of his book the myth persists. A man called Willhelm Hoettl fed the story to Simon Wiesenthal [the famous Nazi hunter] who fed it to Anthony Terry at the Sunday Times where Freddie picked it up and all these people put their spin on it. It is probably true that there were various groups of former SS people and perhaps even one called Odessa in Southern Germany, but the ball has been tampered with so many times and it now lodges deep in the imagination of anyone trying to think about Nazis in the post-war period. But it is a great book with a lot of accuracy and it’s a perfect depiction of post-war Germany.

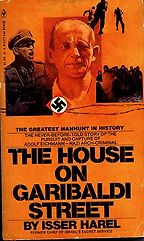

Your next book is The House on Garibaldi Street.

Isser Harel was head of Mossad [the Israeli Institute for Intelligence and Special Operations] in the early 1950s when Mossad found, from the stories of a half-blind German Jew, that Adolf Eichmann was living in Buenos Aires. Mossad went to have a look at the house and decided there was no way he lives in this little bungalow. But the half-blind Jew, Lothar Hermann, persists, and Mossad eventually collected enough information to say that he in fact is living in this crappy little house – actually, another crappy little house – in Buenos Aires, and they staged their audacious, cack-handed, brilliant kidnap of Eichmann off the street in Buenos Aires and took him back to Israel to face trial, and he was hanged in 1962. People say that Harel is trying to exculpate himself for dragging his feet on Eichmann, but in the early 1950s Israel had enough enemies on its doorstep to be worrying about Eichmann and it was not easy for them to mount this operation. The idea that they could have done it straight away at that time is just silly. In any case, Eichmann wasn’t a household name until after his trial, so it wasn’t as if this was a big Nazi name then. This book shows that Simon Wiesenthal, despite his claims, was not involved in the kidnap or search to the extent that he says he was.

Get the weekly Five Books newsletter

Since he turned up on trial in Israel, wasn’t it pretty obvious it was Mossad who kidnapped him?

No. There were a lot of private Nazi hunters at the time and Mossad denied it for ages.

Why so down on Simon Wiesenthal?

Because he’s a liar. He’s just not this secular saint that everyone says he is. His memoirs all contradict each other and are at odds with the rest of the evidence. The Wiesenthal Centre claims 1,100 Nazi scalps, but the true figure is about ten. The Centre bought his name in the 1970s and is basically an Israeli brand builder fighting anti-Semitism. But Garibaldi Street is the book to read about Nazi hunting.

The Tom Bower book, Blind Eye to Murder?

Tom Bower is one of the few decent investigative historians. There are too many historians who just use other people’s books to write their own histories but Bower says; Let’s go back to the source. I find the link between history and journalism interesting. Historians tend to think journalists are spivvy and hucksterish with facts, and journalists think historians piggy-back off other people’s research. But there’s no reason why you can’t be both, like Bower. Anyway, his book is about how we failed to prosecute the thousands of Nazis who went on the run after the war. It is disgraceful that if we thought it was a criminal regime we didn’t go on to prosecute the 80,000 people who committed murders and greater crimes. Nazi hunting basically stopped after 1948 when about five per cent of them had been caught, if that. People like me have to turn initially to this book to work out the extent to which the Allies failed. Read it and it will make you angry. The subtitle is A Pledge Betrayed and this is very accurate. Sure, some Nazis were useful to use against the Soviets in the Cold War, but the extent of it and the cynicism with which things were not done is disgusting. I say this without being naive.

The Last Days of Hitler sounds fairly self-explanatory.

It’s not technically a Nazi hunting tale but Trevor-Roper was working for M16 after the war and he had to piece together exactly what happened to the senior Nazis, including Hitler. Nobody knew then exactly what had happened, and the Russians, Stalin, were trying to make out that he was still alive and being sheltered by us, the British, so it was mandatory for us to show that this wasn’t true. So, he was trudging through the ruins of Berlin and he was an Oxford historian, later Lord Dacre, and this is an amazing forensic detective book capturing Hitler’s last days. It was Trevor-Roper who went on to verify the Hitler diaries which was his downfall, really, but his reputation kind of survived even though he never did produce ‘the great book’. But this is a great detective book and it’s about hunting dead Nazis rather than live ones.

Get the weekly Five Books newsletter

And the Uki Goni’s The Real Odessa?

This is a Granta book that came out in the mid-1990s by an Argentinian-Irish journalist and it’s an excellent story of how he was the first person to go through the files in Buenos Aires from Peron’s time to see how widespread the immigration of Nazis to Argentina had been and how they got there. Peron was, of course, immensely sympathetic to Nazis and brought them in by the thousand after the war. The files have mostly disappeared and while Goni was doing his research there were mysterious fires that destroyed the documents he was working on and things were disappearing all over the place. It is as much about how Argentina came to terms with its dictatorial past as it is about Nazi history. It’s thanks to him that what’s left is left.

Five Books aims to keep its book recommendations and interviews up to date. If you are the interviewee and would like to update your choice of books (or even just what you say about them) please email us at [email protected]

Five Books interviews are expensive to produce. If you've enjoyed this interview, please support us by donating a small amount.