In Why Comics? you explore what makes the medium of comics uniquely appealing and powerful. Although every sentence is worth reading, please give us a precis of your core argument.

In Why Comics? I track how comics started off as a mass media and then became eccentric, outside the center, and now has become a central cultural force. Comics are everywhere now—in bookshops, libraries and universities. One of the reasons comics have become such a big cultural force is that they are enormously intricate and sophisticated. A comic experiments with time and space on the page, which makes it a good form for the artist.

The other reason comics have become such a phenomenon today is because they have a do-it-yourself aesthetic. Many comic artists didn’t envision culture-shaping careers; they were able to do the work they wanted to do, with pen and paper, outside of commercial structures. So I argue that comics are a democratic art form.

“Comics, in its embrace of both the interiority of the written word and the physicality of image, more closely replicates the true nature of human consciousness and the struggle between private self-definition and corporeal reality,” according to the dense dialogue in a panel your book features from Daniel Clowes’s Harry Naybors. Does that sum up your view of the medium’s secret sauce?

In the panel, this incredibly pretentious character is in his underwear, scratching his behind, while eating cereal. But what this character Harry Naybors says in the panel is an excellent definition of comics. And the panel shows the rich tonal variation that you get in comics, where something smart can be earnestly expressed as the pictures make fun of the speaker. There’s this great effort to explain what comics does in relation to other media forms, and a great disregard for the pretentiousness at the same time. To me it is an Ur-example of comics.

So what criteria did you use to arrive at your list of five this year?

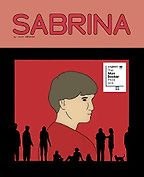

I asked myself which comics felt like serious publishing events in 2018, the sort of events that everyone in the industry and everyone who loves comics would find notable. And I also considered books that were lauded throughout and beyond the world of comics. For instance, Nick Drnaso’s Sabrina was the first graphic novel to be shortlisted for the major recognition of the Man Booker Prize.

Then I thought about titles that were ongoing and important. For instance, Arab of the Future 3 is an ongoing, politically and aesthetically important work. And then I thought about publications that were greeted with a great deal of anticipation like Ariel Schrag’s work.

Let’s begin talking about your list of five with Arab of the Future 3.

Arab of the Future 3 is created by the cartoonist Riad Sattouf who is both French and Syrian. His mother is French and his father is Syrian. This is the third installment in an ongoing series he is doing about his childhood in the Middle East. His parents are at the Sorbonne; his family followed his father, who became an academic to various locations in the Middle East, including to Libya. (The section about his life in Libya is in an earlier volume.) Then his father moved the family back to the village he came from in Syria.

“Comics are everywhere now—in bookshops, libraries and universities”

This instalment of this ongoing story takes place from 1985 to 1987 in France a bit, but mainly in a village in Syria. One really gets a sense of Syrian politics and culture in the mid-1980s, told through the lens of his family. His parents aren’t getting along very well. There are a lot of clashes between his father’s more traditional views and family and his mother’s views, forged during her French upbringing.

One of the things this book does so well is to show how political the personal is, if it makes any sense to invert that idiom. It balances attention to the world historical stage with attention to what is happening within this family—like whether or not Sattouf should be circumcised, and an honor killing in the extended family. Some really serious issues are refracted through the lens of family in a really interesting way.

What is it about the pictorial storytelling that make this such an excellent book?

Riad Sattouf uses color as a narrative force in this book and throughout the series. It’s most effective in this volume. He uses a dual chromatic look for the world that he’s creating in his comics. Different countries are associated with different colors.

The parts that take place in Syria tend to be pink and black. Pink is pretty pastel color that sometimes works at an angle to the violent content of the book. In France, the dominant colors are black and an icy blue, which actually lacks the warmth of the pink associated with Syria. Then, whenever there’s a scene representing anger or violence, it tends to be illustrated in red. I actually mentioned this in a review of this book that I published in my New York Times Book Review column: it’s almost like red is this free-floating country—that he visits more than he would like. It’s a really ingenious use of color to express an emotional landscape.

Is this an example of what you call “the diagrammatic capacity” of comics?

When I was writing about diagrammatic capacity in Why Comics? I wasn’t thinking of color, but of course color can obviously be part of what one looks at when one looks at a diagram. In a way, yes, the color is functioning as a map or a diagram of Sattouf’s world.

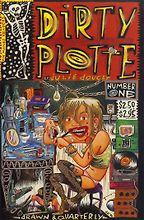

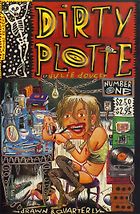

Next, The Complete Dirty Plotte by Julie Doucet. Please tell me about it.

Julie Doucet, a French-Canadian cartoonist who lives in Montreal, decided to call her comic book, which she started self-publishing in 1987, Dirty Plotte. Just to translate, plotte means ‘cunt’.

Julie is widely revered by all sorts of people, so the publication of the Complete Julie Doucet in a box set composed of two hardcover volumes was a huge event in the world of comics. I’ve actually written about her before for ArtForum. She did these incredible comics from 1987 until she stopped making comics in the year 2000, when she turned to printmaking, bookmaking and collage.

Get the weekly Five Books newsletter

There are a lot of gems in this collection. Many of the comics’ plots are feminist, focused on reclamation of the bodily. There’s a lot about sex and menstruation—classics like a well-known comic called “Heavy Flow,” in which she turns into a Godzilla-like figure, bleeding and tearing down buildings while looking for a Tampon. She depicts a surrealistic fantasy escape in which the attention to women’s bodies is violent. There are comics in which the female protagonist character rips off her own breasts and guts herself. A lot of penises get chopped off. There’s a lot of lopping off of body parts in general. Doucet is known for this incredible psychic landscape.

“A lot of penises get chopped off. There’s a lot of lopping off of body parts in general”

That dark, surreal work is beautifully combined with brighter pieces that are more tethered to reality. There’s an autobiographical story called “My New York Diary” which ran across several different issues. It anatomizes the life of a young woman moving to New York City to move in with a boyfriend. The story tracks the decline of their relationship. It is a signal text in feminist autobiographical comics.

So it’s really exciting to get all of her different kinds of work collected together here.

Doucet was classified as an underground or alternative artist. What criteria support that classification? And is the graphic narrative niche more or less taxonomic than the rest of book publishing?

Interesting. So, I think it’s similar to literary publishing. All sorts of terms stick and don’t stick. “Alternative comics”—heavy quote marks—was a phrase that really stuck to describe work that was happening in the 80s and 90s. Many of the same comics artist like Charles Burns and the Hernandez brothers are still publishing, but people don’t call their work ‘alternative’ anymore. Alternative was just one of those eighties and nineties terms anyway, right? Like alternative music. These days, people talk about ‘indie music’ and ‘indie comics.’ So there are all sorts of appellations for comics.

“Independent comics publishing is auteur-driven”

But I think the only one that’s been really important is the distinction between underground—an independent—and commercial. You mentioned Julie Doucet started off in the underground. What that means is that she literally self-published her work. Dirty Plotte used to be a self-published fanzine. Again, there’s so many different words for the same thing, people now call fanzines ‘mini-comics.’ But self-published work is underground work: in other words, outside of any commercial systems of distribution.

Returning to the example of Doucet, she was picked up by Drawn & Quarterly, which is an independent publisher. The independent publishers are distinct from huge commercial companies, like Marvel and DC. They’re not owned by media conglomerates. Independent publishers don’t employ teams of people to produce comics. Independent comics publishing is auteur-driven.

Next in your list is Nick Drnaso’s Sabrina. Why did you select it?

Nick Drnaso made my top five in 2016; I’ve been a fan of his for a long time and I was really happy to see that other people have become big fans of his too through the attention surrounding the Booker Prize.

Sabrina has a really startling story and a really startling style. It’s an amazing economical example of comics fiction today and was appropriately embraced by the world of fiction. For instance, not only was it recognized by prize committees, it also attracted blurbs from the literary likes of Zadie Smith. It’s a very dark story about the kidnapping and murder of a young woman, and the aftermath of that murder and how her boyfriend tries to cope with her death.

“The simpler the rendering, the more a reader can see themselves in the characters portrayed”

Part of what this book does really powerfully is pay attention to the process of mourning and grief. It’s also a searing media critique: it comes out in the story that the person who had murdered Sabrina had had filmed the murder, and the tape is leaked. The book takes on the painful subject of conspiracy theorists who deny that the murder happened. So it becomes a book about mourning and modern media, rendered in a minimalist style that’s very stripped down and effective given the maximalist parameters of the plot.

The pallid palette and the rigid, almost digital lines don’t seem too telling or engaging. What does this book tell us about the diversity of drawings in comics?

A couple of things. First, there is a lot of attention to expressiveness in this book. The characters’ rigid, blocky bodies draw readerly attention to the characters’ faces. For instance, the cover is just a stripped-down, three-quarters-angle portrait of Sabrina. So, like all the panels, attention is drawn to the face. It invites readers in a participatory way to look for reactions in gestures, body language, and facial expressions. This is a quality of comics that Scott McCloud talked about: the simpler the rendering, the more a reader can see themselves in the characters portrayed. Sabrina is a really good example of that. We find ourselves searching the faces on the page.

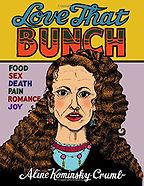

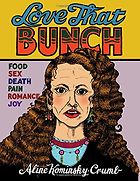

You penned the foreword for Love That Bunch, an Aline Kominsky-Crumb collection. Why did you choose it as one of the best comics of 2018?

This beautiful hardcover treatment of Kominsky-Crumb’s collected comics was a huge event in the world of comics. I absolutely love this work. It’s very dark, very bodily, and very funny. There’s a lot of humor in her stories about her upbringing on Long Island and her life as a middle-aged woman living in France. It’s just a really fascinating collection about the everyday qualities of life, from an author and artist who has been very influential in the world of comics.

Aline Kominsky-Crumb has a totally nutty style that I find unbelievably charming. She has called it scratchy and raw and ugly; I’ve always loved it. It’s the style in which there’s not a lot of attention to things like perspective or proportion. It’s often quite anamorphic—you get a lot of shifting proportions and sizes. She even draws herself differently from panel to panel, which conveys a fluidity of self, or the the fact we ourselves are always changing and never totally stable.

Kominsky-Crumb was part of a feminist comic collective, you note in the foreword. This made me wonder: are comics more malleable to alternative viewpoints than more staid media?

That’s such an interesting point. I do think that that’s true because the bar to entry is so low. That is to say, all you really need to get started is a pen and paper. Or if you’re not working with pen and paper, Allie Brosh, an incredible cartoonists who did a blog and then a book called Hyperbole and a Half, made her work using Microsoft Paint, which is a free software program that came with her computer. So a comic isn’t necessarily about beautiful rendering. It’s about a kind of expression. Unlike making a film, people can make comics without a big apparatus. Unlike writing a novel, people can self-publishing, they can find outlets in the thriving micro-presses and they can reach readers through the underground comics world. Because comics can be such a do-it-yourself medium, it is a vital outlet for alternative viewpoints.

Ariel Schrag’s Part of It is your fifth choice. Why?

Ariel Schrag, who’s now in her late thirties, started doing autobiographical comics about her life when she was in high school. She did a separate comic book series for each year of high school; they have separate names and series names like Awkward and Definition and Potential. She’s very good, though not as prolific these days, so it’s so exciting to have a new autobiographical work from her.

Five Books interviews are expensive to produce. If you're enjoying this interview, please support us by donating a small amount.

This book has an ingenious structure. It flows year by year through her young life, through collected chronologically-ordered autobiographical stories each labelled with a title, a year and an age. The first story is called “Jilly,” which is the name of a childhood friend. Unlike Aline Kominsky-Crumb, who weaves in and out of fantastical stories, we can follow this protagonist’s development, including her attempts as a young person in middle school to fit in, and then her coming out and then her attempts as an older person to fit into different kinds of social scenes.

Do the dynamics between words and images in Ariel Schrag’s work and all quality comics possess the potential for immersing readers more deeply into the stories they tell?

The dominance of digital and internet and online everything in our lives has made us all more sophisticated about the interplay between words and the images that inundate us, the logos, graphics and photographs. But there is something specific to the simplicity and intimacy of the dynamics between drawing and words that makes comics more relevant today. I feel like all of the work that I chose exploits that intimacy in different ways.

Interview by Eve Gerber

December 14, 2018. Updated: December 23, 2018

Five Books aims to keep its book recommendations and interviews up to date. If you are the interviewee and would like to update your choice of books (or even just what you say about them) please email us at [email protected]