Can you tell us how you started thinking about gods and god-like figures in science fiction?

I’m fascinated by the ways people perceive their place in the universe—and that of things that are beyond and greater than them. What I’ve always found interesting is that there’s a range in how authors deal with these themes in speculative fiction, both in science fiction and fantasy. Some have the gods being very present and meddling, and some have them more off to one side.

My favorite novels are the ones in which there’s a discovery aspect. Either the protagonist has had a view of God or the gods and that view is challenged, or they have not even perceived the possibility and it comes upon them all of a sudden, and it always causes a huge, huge change in the protagonist’s character arc, their life, and the choices they make afterwards.

Your first recommendation for us is Till We Have Faces by C. S. Lewis. First of all, can you introduce our readers to this book?

Everybody knows of C. S. Lewis because of The Chronicles of Narnia or The Space Trilogy. My controversial take is that the Narnia series is the point at which C. S. Lewis begins to get good.

Till We Have Faces was C. S. Lewis’s last book. He considered it his best —we’re in agreement there. It’s his retelling of the myth of Cupid and Psyche. Many people might not know that C. S. Lewis also wrote a lot of religious nonfiction. In this book, not only do we see his love for Greek myth, we see him working out theology questions that he’s been pondering in his life, throughout his studies, and in his fiction.

I absolutely love it because, first of all, it features one of the best female protagonists I’ve ever read. And that’s saying something, because when he started out in The Space Trilogy, he did not write women well at all. Till We Have Faces follows the character’s arc and her relationships from when she is a young girl to when she becomes an old woman. It’s especially about her relationship with her sister, who’s the one chosen by the gods.

“Some have the gods being very present and meddling, and some have them more off to one side”

Lewis has managed to ground it in a world that feels real: this quasi-Mediterranean ancient society in which the Cupid character and the Venus character are more like these older gods, but the idea there again is that you have the religion, the god, the structure, and everybody telling you this is the way it is. Then, when the actual manifestation of the real deity turns everything on its head, what do you do?

Here the protagonist makes a really interesting choice: she denies it.

Her sister is trying to say to her, ‘Look, I know all these things are true because I’ve experienced them.’ The protagonist can’t accept it because she can’t see things from her sister’s perspective. Then, for a moment, she’s shown everything that her sister sees, and she effectively says, “I can’t handle this,” and she backs away from it. And that’s where her story begins.

That, to me, is fascinating. The whole change of her character, everything she has to deal with as a leader, the disappointments in her life and her achievements—all are done in a way that is incredibly thoughtful and incredibly profound, and shows that you can’t separate your relationship with the numinous from the things that are mundane in your life. They are always intertwined.

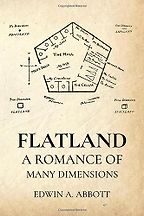

Your next recommendation for us is Flatland by Edwin A. Abbott. For any readers who haven’t encountered it, could you introduce us to this unusual book?

Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions is an old book that holds up incredibly well. It was published in 1884 under the pseudonym ‘A Square.’ This extremely slender volume takes you on a journey through various dimensions. The protagonist, a square, lives in a two-dimensional world and is introduced to the concept of three dimensions by a sphere.

The book contains thought experiments, such as how to picture something from a different angle. If you did geometry in secondary school, you might remember when the teacher tried to explain a tesseract to you. When you try to picture a four-dimensional cube with your three-dimensional mind, you can understand what the poor squares are going through.

In this book, the description of Flatland society is a sharp critique of society during the author’s time. Women are straight lines and are considered inferior. They have their separate little world. Criminals are isosceles triangles and they can’t change because that’s the way they’re made. Abbott makes all of these commentaries on society conforming to a very particular structure.

Get the weekly Five Books newsletter

Circles are perfect, so when the square encounters this creature from another dimension, and it’s a sphere, he thinks, ‘Oh my goodness, circles—the height of perfection.’ The square lives in a rigidly structured world that he totally believes in, so when this entity appears from beyond and says, ‘look at these dimensions,’ that’s the encounter with the god-like object.

Something fascinating happens; the square then says to the sphere: ‘Wait a minute. If there are four dimensions, then surely there are even higher dimensions.’ The sphere says: ‘Whoa, we don’t go that way. There’s no perfection beyond mine. I’ve come to educate you. Why are you being like this?’

The square thinks, ‘This is not a god. This is someone who has come to mess around with our perception of being and feel good about it.’ It’s absolutely hilarious. The square becomes an outcast, but the job is already done. He’s already started questioning his perception of society because he’s been shown that even his physical world is not what he thinks it is, so he begins to rethink his social world. He questions what he has been told about women, about criminals, and the whole class structure that’s in place, which is based on how many sides each person has. The idea is that if you’re very careful about who you marry, your children will have more and more sides. Your family will achieve higher and higher levels, and eventually produce a priesthood-level circle.

The square starts questioning all of this, and it’s something that would not have happened without that rupture that was brought about by someone saying to him: ‘The physical world is not what you think it is.’

In Till We Have Faces, the deity that presents itself is real; in Flatland, the deity is not real, but the epiphany—the revelation—still happens. It still opens up his mind and makes him think: ‘Wow, there’s more going on here than I realized.’

The deity doesn’t have to be real for the epiphany it creates to be real, I love that. The next recommendation you have for us is A Wrinkle in Time by Madeleine L’Engle. Can you tell us about this science fiction book and its gods or godlike characters?

I borrowed it from the public library and ended up inhaling the whole series. A Wrinkle in Time is the first book of the Time Quintet, and it’s followed by A Wind in the Door, A Swiftly Tilting Planet, Many Waters, and An Acceptable Time.

In a sense, it’s science fiction. But it’s laced through with a deep thread of theology. The protagonist, Meg Murray, encounters angels and she encounters an absolute evil. In this book, a deity—in the sense of absolute good—does not show themselves, but their subordinates, the messengers, the ones who help to do the will of the supreme being, are all very present. The spiritual elements appear side by side with the physics aspects in a way that you don’t often see being done either in children’s literature or in speculative fiction.

In A Wrinkle in Time, when Charles Wallace and Meg encounter ‘IT’, the idea is that enforced conformity is the evil they have to push back against. I honestly don’t know if this is a bias of artists, but a common theme in many of these books is that, as the result of an epiphany, the person has to push back in some way against society as they think they know it. The structured place, the rule-abiding place, the place that I described to you in Flatland, is actually the bad place. It’s the place that is ruled over by people who are trying to keep you in a box, to keep you within certain structures and rules, and it is not a place for free thought.

“In a sense, it’s science fiction. But it’s laced through with a deep thread of theology”

Here is a book that presents to the young reader the idea that conformity is bad, that you shouldn’t say everything everybody else does. You shouldn’t bounce your ball in time with everyone else; you should be able to bounce your ball to a different rhythm. In a book that’s supposed to be middle-grade level, that’s quite a subversive message, and I find it lovely that it’s presented.

A lot of people have not understood A Wrinkle in Time very well. Some people are offended because of how it treats Christianity, and some are offended because Christianity is mentioned at all. I say, strip away those things for a second: yes there are cherubim and guardian angels and the fight between good and evil, but look at that message about conformity, question your society, push back against what society expects of you. That’s the bit that I think everybody should be looking at and thinking, ‘wow, that’s right.’ Start them off early because they’ll need to know this, especially if they’re creative.

Do you think that we overly associate gods with goodness? Do some of these books challenge the idea that just because a being is more powerful than you, they necessarily have more moral standing?

You raise an important point, because fictional gods do run the gamut. Your question leads into the next two book choices. On one hand, it could be that an entity has more power than you do, so you must bow down to it no matter what. On the other hand, it may be that an entity has a different consciousness than you have.

For example, as much as you may love your dog, you accept that your dog has different mental processes to you, and that they may have a different perception of getting shots at the vet, or being on the leash, or whatever. Some of that is simply difference, but some of it is having a higher consciousness of your brain.

In the case of an omniscient entity with a literal ‘galaxy brain,’ what you think of as morality doesn’t apply because you don’t have all the information.

In literature, you have various fictional depictions of gods, ranging from the brutal and cruel to the benevolent and loving, and you see the same spread within the religions of the world. Some of this has to do with us not understanding fully what their motives are, and some of it is us projecting our own selves onto them: ‘If humanity behaves like this, then our gods must behave like this.’ We don’t have a clear definition of what divine essence is.

I believe this is something you explore in your new book, The Blue, Beautiful World?

I do. The protagonist is a celebrity, when we encounter him. Celebrity worship is coming up quite a bit in the discourse lately, although it’s not a new thing in human civilization. The protagonist’s mentor tells him that his job is not to be a god but to be glue, the idea being that when you have that attractiveness, when you have that charisma, your job is to create community, to bring people together, to have them face each other, make bonds with each other, and not to have everyone turn and worship you.

Because he has this unique capacity, he’s tempted to use it in different ways, but he has examples from his past—his father had a similar quality and misused it terribly. So he’s conscious that having that much power, in a setting where no one’s strong enough to stop him, is a terrible terrible tightrope to have to walk all the time. I won’t spoil how he manages to resolve this dilemma.

I’m on tenterhooks. I can’t wait to read it. The next book on your list for us is The Tombs of Atuan by Ursula K. Le Guin. Can you introduce us to this classic sci-fi novel?

So this is my second children’s book-type choice, but when I first read it, I thought that—although it has a young protagonist—the atmosphere and pacing are very adult in some ways.

The protagonist, who has been ordained by her religion for a special position, has a very structured life, is in charge of performing certain rituals and so forth. She both has power and has vulnerabilities, in the sense that she has no escape. It’s a weird position to be in. On the one hand, she’s in a very powerful position, and on the other hand, there are some bonds she just cannot step beyond.

Then she encounters Ged, who is the protagonist from A Wizard of Earthsea (which is the first book in the Earthsea Cycle). Ged is her point of epiphany, because once more we have a situation where she starts to question. He’s supposed to be killed by her hand, because he has trespassed where no one is supposed to trespass, but she keeps him alive, and it just begins to unravel from there: she begins to question, and she begins to see the world in different ways.

“Epiphanies can be… I don’t quite want to say accidental, but they can be impersonal”

The book does not have a perfect YA ending, with the two of them getting together and living happily ever after. Ged says, ‘I’ve got stuff to do, and you’ve got stuff to do, and we can hang out when we can.’

This shows that epiphanies can be… I don’t quite want to say accidental, but they can be impersonal. If someone gives you an epiphany, it’s not a promise or a love bond. They do not necessarily become your master or your mentor, or guide you through this. It could be simply that they are bringing you a new perspective and understanding of the world. If that upends things for you, they may have compassion for you, but they won’t necessarily accept responsibility for it.

Ged very firmly declares, ‘I’m not a god. I’m not there to replace the new hole in your life, now that you’ve gotten rid of all this old stuff. You’ll have to do that on your own, and it’s not going to be me to fill that gap.’ I wish everyone would have that courage. Some people would rather be the celebrity, they’d rather be the person to guide you through it. It’s remarkable to be able to say, ‘You know what? I’m glad this was meaningful for you, but now you’re on your journey, and I’ve got things to do.’

There are people who want to be small gods for others, and people who are looking for someone to provide all the answers and abdicate responsibility for their own choices. It’s a fascinating dynamic from both sides.

Exactly, and how clever of you to slip in the title of the last book.

It felt clever! Your last selection for us is Small Gods, by Terry Pratchett, from his comic fantasy series Discworld. Could you introduce us to this book?

I absolutely love this book because it depicts a push-and-pull situation. In Discworld, Pratchett has set up a world where the power of faith is something that humans have but don’t fully understand, and it can literally create things. So the gods in Discworld are a function of the strength of the belief of their followers.

This is a beautiful, crazy concept, and Discworld is full of these beautiful, crazy concepts. And yet, it’s not that farfetched, because when you have a particular format in which you squeeze your idea of deity, the larger the church or the religion, the more you are able to continue to perpetuate and enforce it. So it’s not coming out of nowhere.

What we have in Small Gods is a situation where the church has continued as an edifice, but doesn’t necessarily believe in the god around which it has structured itself. But there’s one young novice who truly does believe that this god exists, and has the opportunity to encounter this god.

Five Books interviews are expensive to produce. If you're enjoying this interview, please support us by donating a small amount.

The god is not a pleasant entity; he’s small and petty-minded, and it’s funny: this is his personality, you can’t even argue that he’s like this because the believers’ faith in him is not strong enough. Even when the god eventually acquires more power, he has the same personality; he’s learned to appreciate the novice but hasn’t evolved as an individual, so to speak.

You begin to understand that the difference between a small god and a god of all that power lies with the people who mediate that god to the real world, and who are responsible for the inquisitions and the services and the rituals—especially the rituals, because of the life thresholds things, like birth, death, marriage, sickness, and so on. Most religions have rituals around those essential areas of our lives, and that has a lot of power.

Another interesting thing that Pratchett is saying is that while religion centers around the questions of whether or not this god exists and whether or not this god is benevolent, there’s also the structure of the religion itself—in terms of what role humans play in it and how these humans behave towards other humans.

That is the epiphany that the novice has to have. Yes it’s nice that he discovered his god was real, and that, even though he had to come to terms with his god’s personality, he didn’t just fling up his hands and say, ‘if you’re like that, I can’t believe in you anymore.’ He realizes his responsibility in being the person who mediates the presence of the god to the people around him.

You have a PhD in sociology of religion. How would you critique these books as a sociologist of religion?

I did not study an aspect of sociology of religion that allows me to critique these books in that light, but I think these books are very good at examining different aspects of how human beings encounter the concept of religion, how they encounter the concept of divinity, and how we deal with having our universe upended. These can be three separate things, but sometimes they all happen together.

I like to see that level of maturity in works. You come across quite a few books, especially in the fantasy genre, where the gods are present, they have very set duties and personalities, they may battle each other, but there’s no real concern or conflict in how the people are dealing with the god. It’s almost as if they’re just dealing with an exceptionally powerful leader. It almost removes that sense of additional—I don’t even quite know what to call it. Complexity? Depth? Nuance?

To go back to Narnia; Aslan is very present and I would say that may be part of the function of Lewis starting to work through and develop things and so forth. But even aspects like Susan’s disbelief, or Edmund’s betrayals, or Eustace being a nasty person who has to get over himself, are fascinating things to consider, because Aslan is present and dealing with them in a way where he brings them truth.

There’s even a point where Lucy—who is portrayed almost as his favorite, but Aslan still doesn’t let her off the hook—when she eavesdrops on a friend’s conversation, and it was something that she shouldn’t have done, and she looks to Aslan to say, ‘I understand.’ Instead, he says: ‘You’ve ruined your friendship by doing this.’ There’s no apology, no softening. He lets her know it’s a problem. It’s going to be hard.

That openness and honesty is showing you the universe as it is. We all go through life with our own biases and filters and veils that allow us not to look too closely at certain things that make us uncomfortable. The books that impress me with how they portray deity are precisely the ones where some kind of truth has to be faced.

Maybe the not-god is secondary in bringing it about, like in Flatland, where the epiphany becomes independent of the sphere, who’s not really a deity, or in Small Gods, where the small god has a terrible personality and his novice ends up being in some ways better than him. But the process remains the same: it’s facing reality to come to terms with a reality that is not the one you would have previously accepted.

Interview by Uri Bram

August 30, 2023. Updated: June 11, 2024

Five Books aims to keep its book recommendations and interviews up to date. If you are the interviewee and would like to update your choice of books (or even just what you say about them) please email us at [email protected]