Before we get to the books, I’d love to get a sense of Mumbai as a city. I know many people from Mumbai are deeply attached to it and very proud to be from there. What’s it like from your perspective, as a local?

A line that I wrote in my own book is that it’s a city where everything and everyone lives a little on top of someone else. Every house is on top of another one. Foods meld. Languages meld to make Bambaiya. It’s a city where everyone lives cheek by jowl, everything is mingling into everything else because it’s a slim, island-shaped city—kind of like New York—but with 18 million people living here. It’s one of the most densely populated cities in the world, almost coming apart, but not coming apart.

The lockdown has made us think about how we are living in these cities. In a way, we are not living here because we’re not stepping out as much anymore. We have very much retreated into our own homes. Then, stepping out, you reclaim it in a very different way. This is one of the busiest cities in the world, but when you step out, it’s totally quiet. You experience it in a very different way. It’s always going to change, but not really changing.

They say that in the world many mega cities are alike now. When you go to London, to New York, they feel a little bit similar. Bombay has resisted being one of those big global cities because it has defied that complete modernization. It remains singular, partly because it’s almost crumbling, but not crumbling. It’s holding together in that very, very tenuous way, as are our lives here. They’re very tenuous but still going. That requires that fierceness, that sense of fun, of irreverence, of breaking every stereotype, of firmly moving, constantly moving, but almost staying in the same place.

As a visitor to Mumbai, it comes across as this extraordinary, vibrant place. But also striking—and this is key to your book and some of the books you’re recommending—is the extreme inequality. A few years ago, we read that India’s richest man had built his own skyscraper to live in. At the same time, if you fly to Mumbai, your first vision is the slums as the plane descends onto the airport runway.

Yes, it’s true. Mukesh Ambani, who you’re talking about, is one of the wealthiest people in the world and yet more than half the city lives in a slum. That slum is really just thin sheets or plastic sheets. Or you put two saris together. You just put the saris anywhere, on the pavement, on a railway track and it’s your house. Bombay has one of the fiercest monsoons in the world. So, when the monsoon wind comes, your house is literally walking away. I remember my editor saying, ‘How can a house walk?’ And I said, ‘Just come here and you’ll see’. I think I wrote in my book that it is like a drunken walk because it walks with the wind and, as the wind stops, the sari collapses on the ground. Then, when the wind comes again, the sari house is flying again. It shows you how tenuous people’s lives here are. That is the kind of inequality.

“It is a city of outsized dreams, whether those dreams come true or not”

There is a book called Billionaire Raj that talks of that famous house, which is supposed to be one of the most expensive houses. It’s not the only one: real estate prices are among the highest in Mumbai of anywhere in the world because there’s so little space. What are you seeing from that house? You’re seeing fishermen’s houses, slums. That is the view. It’s a complete melding of two very different things together and, somehow, there is a comfort with it.

What do you mean?

There’s a low level of violence. With so many cities with this level of inequality, there is, ‘Why am I not living in that house? What can I do to get a bit of that?’ You’ve heard of carjacking and kidnapping and ransom elsewhere in the world. I believe that the wealthy in some places even use choppers to travel within the city because they are worried about their safety. The wealthy live in a very different world.

But here in Mumbai I would say, ‘Okay, the wealthy may not be visiting slums, but that is what they’re seeing.’ And you may be traveling in your fancy car, but somebody will come and knock on the window and ask you for money and you might just roll your window down and give that person money. It’s not like wealthy people are getting murdered and kidnapped for money or ransom or any such thing. There is an uncomfortable but lasting peace with that inequality.

And I often wonder why that is. It’s because it is a city of outsized dreams, whether those dreams come true or not. There is that sense of possibility that I could be somewhere, that I could be someone. It is a somewhat unreal dream, but people are living off of trash and making some money. It is an unreal dream, but it is a dream. It’s the dream of and the promise of cities. It doesn’t often come true, but people live that dream. They live in that hope. That is the point of all big cities, like New York or London, that I’m just a step away from being wealthy or famous.

Now, you’ve written a book about the waste pickers of Mumbai, but you also run an NGO, the Vandana Foundation, set up, initially, to support the city’s poorest microentrepreneurs. How did you come to do that?

I was a journalist for many years, and I used to write about a lot of different things. One of the things I wrote about was financial inclusion. In the US, it’s called redlining, that if you live in certain not-nice parts of the city, then financial services or even pizza delivery will not come to you, or bank accounts are not available to you, etc. So, in 2010, I left journalism and started this nonprofit. The idea was to give low interest microfinance loans to microentrepreneurs.

It was this amazing opportunity to almost look at the city though a bottom-up lens, if I may say. It wasn’t intentional, but it happened because we were getting people who were making street food, home-based tailors, people who made soft toys, all the cobblers of the city came to us. I got to know what the different communities were, what they were doing, where they were getting resettled from. I had a sense of curiosity and even walked on those water pipes that you see in the movies, those long snaking pipes with people living on them and their neighbour living on the opposite water pipe.

We worked with many very amazing communities from different parts of the country, one of which was in 2013, when we began getting waste pickers from the Deonar garbage mountains saying, ‘We want loans.’ And I said,’ Well, you only pick what you can with your hands, what are you going to do with our loans? Our loans are going to go bad!’ And they would say, ‘No, no, no. You have no idea, this work is only going to increase, do you think the city is going to stop shedding trash? That is not even possible.’ So I said, ‘Fine, let me see what you do.’ So I started going there, and I developed this crazy, dark obsession with the place. It became clear to me that this was not a slum like any other slum I have been to because they were earning some money, sure enough. Trash never reduces, it’s like a sunrise industry in a city like Mumbai. And the waste pickers would say, ‘this is a great business’. It was also, I thought, a way of looking at ourselves because it was our trash arriving there: toys and coffee cups, Chinese food, makeup, whatever it might be.

Deonar garbage mountain, Mumbai

Deonar garbage mountain, Mumbai

So I was looking at their lives made of this trash, earning some money. But poverty is not just money, it’s also on their person. They had cuts, they had bruises, they were bent. Many of them had tuberculosis. Three of the characters in my book died while I was writing it. Their life expectancy was extremely low, education was low, addiction was high.

It just made me more and more drawn to this place. It was saying something about the city, but also about our contemporary world. We accumulate things—I certainly do, as someone who lives in a nicer part of Mumbai city: a new pair of heels, or a dessert, a chocolate, a new phone. India is the world’s biggest market for phones, and phones often end up in Deonar, a few months after they are bought. These guys fix it up and use it again. They were making their lives off of this trash, but it told me something about us wealthy people too. We hoard all this stuff thinking it will satiate us, but it ends up there. Surely this is not what gives meaning to our life, if it ends up making 16 million tons of garbage mountains?

At that point did you decide to write a book about the waste pickers?

In 2016, from January onwards, there were huge fires there throwing up lots of smoke and those fires were captured on NASA satellite pictures. Then the whole city was coughing, wealthy people were coughing and had asthma. It was as if this place had suddenly entered the city’s consciousness. Waste pickers were getting detained by the police for lighting the fires, which they may or may not have lit. I thought that because I knew these waste pickers that I would write a magazine piece about our connection with this place—this very combustible, huge place that we made. But before I could get it published, I kept researching and researching and researching until it became a whole book.

Let’s talk a bit about the books that you’re now recommending about Mumbai. How did you choose them, what were your selection criteria?

It was just how much they moved me. I had a hard time selecting these books. I thought of a few Marathi books. I’ve used all three languages in my book: there’s bits of Hindi and Marathi and of course the book is in English. I do speak, read and write all three languages with equal felicity. So I thought of having a Marathi book and a Hindi book, but that just made the selection so wide that then I decided to keep it to English. These are really my favorite books on Mumbai. There will be an equal number that I’ve left out, but some of these are books that I’ve grown up reading, that I’ve learned something from and, maybe unconsciously, they may have influenced my own understanding of this city and may have flowed through my hands while writing unknowingly.

Let’s start with Ravan and Eddie by Kiran Nagarkar, which is a novel about two boys growing up in a chawl. What is a chawl, by the way?

A chawl is like a tenement. It’s these long, low-slung buildings that really characterized Mumbai at one time. Some had sloping red tile roofs. It’s communal living in a way, these one-room houses, with long corridors and a shared bathroom and toilet at the end, maybe among 20-30 families. So, again, foods are melding when somebody is cooking, going into someone else’s house, children are all intermingled, you don’t know where your child is at the end of the day. Often the design is that there’ll be a courtyard in the middle. Mill workers lived in them and maybe they were made originally for single men, but then later they just bulged with families like you see in this book, 8,10, 12 members of a family living in one single room.

They became so characteristic of Mumbai at one point, with all kinds of festivals being celebrated and movies made about living in a chawl. The famous Aesop’s fable of the hare and tortoise, there’s a Hindi movie of it, about these two neighbors living in a chawl.

Get the weekly Five Books newsletter

In Ravan and Eddie, Kiran Nagarkar has used that thread of intertwining communal living to show so many things about Mumbai city. Ravan is a Hindu and Eddie, his neighbor, is a Christian. He shows how their lives are tied together in the most comical, irreverent way, and yet with bits of darkness, tragedy, seriousness. It’s very humorous. We see everything through the lives of these two children, who we see right from birth until they are older and coming of age. They’re intertwined from birth, I’ll tell you how: Ravan, as a baby, had fallen from the window of his chawl onto the father of Eddie who had died when trying to save him. Then the mother is taking him in an ambulance and Eddie is born. So their lives are stuck together forever.

It’s very characteristic of Mumbai city where different religions and different languages mix in the most unexpected ways. It is Eddie who joins the Hindu right-wing RSS and it is Ravan who drops out and ends up uninterested in right-wing Hindu nationalism and doing totally different things. It’s very irreverent, very funny and, at the same time, underpinning the comedy is the pathos of living like this, the tragedy of living like this, of families living these outsize lives in this very small space and with very little.

What period is it covering?

It’s set in the 1950s. So there is still a patina to Bombay city, it’s still nice, it still feels a little sanitized, a clean space for ideas, a space for thoughts, which is also what you see in this book. It’s one my favourite books about Bombay, just for its sense of fun and unexpectedness. It’s a great entry point for someone. Although it’s set in the 50s, ultimately it’s about two boys having a wonderful childhood.

Let’s go on to the next book about Mumbai you’re recommending. This is Em and the Big Hoom by Jerry Pinto, which is a novel, but also somewhat autobiographical, about the author’s life. Tell me more about it and why you like it so much.

It’s about a family, the mother and two children. The mother suffers from bipolar, and the two children are remembering growing up with her. When she is lucid, she has the most beautiful memories of her long courtship with their father. When she is not so lucid, she is very acerbic, sharp, with a temper, and then you see her completely in the throes of depression and the children having to deal with that. It’s deeply emotional while, at the same time, having that sharp, raw voice.

The way he’s shown family life with such tremendous emotion, it just breaks your heart completely. Mingled with everyday mundane things that happen in families, suddenly it could be that the mother needs to be taken to hospital, or there’s blood on the floor. That mingling of the mundane and the heightened emotional experience of the mother just totally grips you.

He’s also used dialogue very beautifully. What is Bombay English? This is a great example. The city is such an amazing character in the book because Jerry has lived in this city his whole life. He was born here. I’d also like to mention his other book, Murder in Mahim, which is a murder mystery. Em and the Big Hoom is set in this particular part of the city called Mahim, where a lot of Catholic people live and he is one. The seasons, the trees, the flowers, the urinals, everyday life is mixing with this very emotional experience of living with a mother who has bipolar—facing it every day, living with it, you almost being the adult sometimes but then the mother being the mother sometimes. It’s just beautiful and moving.

Is Murder in Mahim about his family as well?

That’s not about his family, it’s a murder mystery. In both the books the city and this area, Mahim, comes out as an amazing character. You see the trees, the seasonal flowers, the urinals, the trains, the smallest railway platforms, the Sunday lunches. He’s used the character of the city so beautifully in both these books.

Let’s turn to the next book, which is Miss Laila, Armed and Dangerous by Manu Joseph. For this book, it might be helpful to know what the Sangh is, so maybe you can explain that?

We’ve touched upon it even with Ravan and Eddie. It’s called the RSS and it’s a Hindu nationalist organization. It was meant only for men, and they wore khaki shorts. They would go out to do exercises every morning, but they were also learning many cultural aspects. They were being taught right-wing thoughts. For many years it was reserved for men, but if you see the cover of this book, the main character is a woman wearing khaki shorts and high heels. So you know right away that this is a genre-bending book. This is part of the reason why I chose it, because it has these two women characters who completely defy any stereotype: they are irreverent, sharp, fun, unexpected, which makes them such Bombay characters.

This woman in the shorts, Akhila Iyer, is trying to make prank videos (this is pre-Tik Tok), where she corners men and asks them uncomfortable questions. She has views on everything: she doesn’t like anyone who is a socialist, Marxist, environmentalist, eats salad and she wants to corner them by making videos. Akhila finds this very Bombay incident of a building collapse. She’s just gone out for a run and a building has collapsed in a heap. She’s called to extricate a man who is stuck in the debris. This man is muttering some secrets thinking he’s going to die, and through those she uncovers what is called an ‘encounter killing’, a police shootout. It’s based on a real-life incident. A young, suspected teenaged woman terrorist has been killed by the police for being involved in a plot to kill a person who later became Prime Minister of India, who happens to have been a member of the Sangh. He is a thinly veiled character in the book. There are lots of thinly veiled characters, lots of satire, and I love that there are women at the center of it.

So this encounter killing, this ‘shootout’, was a very much publicized incident where a teenage Muslim girl had been killed and there was this whole debate about whether she was a terrorist or she was not a terrorist. And so while this is a piece of fiction, he uses it as an entry point, through the debris of that building, to make these irreverent but at the same time, very, very sharp, observations about the city, about the country, about what is going on in our country. It’s some of the sharpest social commentary you will see about our times. And he spares nobody.

Is the book harder to understand if you don’t know Mumbai and everything that’s going on in India? Or is it a quick way of learning about it?

I think you would enjoy it anyway because it’s full of his sharp commentary and full of humour. Manu is known for his clever insights and it’s full of them. So you will enjoy it anyway and it will give you a wonderful understanding. The rise of the right wing is not only in India, it is also happening elsewhere in the world. It gives you a sense of what is happening here, but it does give you a sense of what is going on elsewhere. And it’s full of these outsized, unforgettable characters.

The next book you’ve chosen is a work of nonfiction and it’s about one of Mumbai’s slums. Tell me about Rediscovering Dharavi.

This book is by Kalpana Sharma who is a doyen among women journalists in our city. It’s about Dharavi which is known as the largest slum in Asia. To outsiders, even within the city, but especially to westerners, slums feel like dark, uninviting places almost, but she takes us into Dharavi and just makes it so full of light and enterprise and this tremendous, wonderful, positive energy. It’s a microcosm of the city and of the country because she shows you how all these people from different communities, from different parts of the country, came to occupy this place. So, say, Tamilians came from here and set up tanneries and Gujaratis came from there and set up the potters’ community. All these communities have their own little lanes, their corner of Dharavi is a microcosm of where they came from. They speak their languages, continue the businesses of their ancestors, and eat those foods.

Then there are the fisher folk who were supposed to be the original inhabitants of Dharavi, but then the sea got reclaimed and the city grew over it and people came from all over. She is showing us how the city was built.

When I started my nonprofit, we also began a lot by working in Dharavi, so these lanes are very familiar to me. The sun does not seep into them, but you will find fish drying there, home made crisps drying there. I don’t know how they dry in the dark, but they do. You’re walking on drains, turning corners, going down blind alleys and suddenly finding, ‘Oh, there’s a glove factory here!’ There’s beautiful embroidery being done; expensive wallets being made. Some might be sold as European designer labels, maybe. It’s like a microcosm of the whole city, of the whole country, of the whole world in this tiny place.

We haven’t talked about the tensions between Hindus and Muslims in Mumbai: does that come up in this book?

She talks about it in her book, I talk about it a little bit in my book, in Manto’s book he talks about it. Bombay was a city where because of the lack of physical space there was tension, but there was a lot of intermingling also. It was home to wealthy Muslims, the biggest movie stars were Muslims. So this was a city where people mingled, life mingled, food mingled, but certainly after the 1992 riots—which she talks about and I talk about—there has been a ghettoization in the city. Muslims have moved out to the flinty suburbs of the city. Housing has become segregated in the name of food. That bias associated with militant vegetarianism is more in Bombay than in any other city. So you can only live in some nice buildings if you’re vegetarian, which Muslims and some other communities of course are not. It’s a way of keeping them out.

So the city has become segregated, and then there’s redlining, which I talk about. If you now live in that flinty suburb, your pizza will not get delivered to you, credit cards will not be delivered to you, banks are not there. Life now has got segregated; I don’t think it’s fair to say that it has not. What can I say? My book is about the dumping ground which is now mostly Muslim: those who could move out moved out and they were mostly Hindus.

I’m quite interested to hear you refer to it as Bombay and sometimes as Mumbai. Do people use both names?

They do. I have a great love for Marathi language which is the language of Bombay. I was born in Pune which is just a few hours away and is a much more Marathi speaking city. It was in Marathi that the city was originally called Mumbai. So when I speak in Marathi, I will always call it Mumbai. But Bombay is also a colonial city and they called it Bombay. Bombay is the city we grew up in.

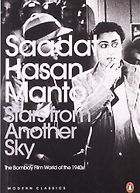

You already mentioned Bollywood and the film/movie industry which is another aspect of the city and it’s what your fifth book is about. It’s called Stars from Another Sky and it’s by Saadat Hasan Manto, who was a great short story writer in Urdu. It’s reminiscences about his experiences in 1940s Bollywood.

Before he became a celebrated short story writer, Manto was the ultimate Bollywood struggler. He wrote scripts for Hindi movies which hardly anyone has seen. Actually, I suspect he wanted to be in the movies and write movie scripts just as much as he wanted to write short stories.

When people from small towns come to Bombay, they love it like ‘stars from another sky’. They love that starriness of Bombay city. This is the first of that kind of writing, where he is wanting to mingle with the movie stars. He’s making friends with them. He’s talking about their life. He wanted to make it in Bollywood more than anything. So he’s talking about Bombay of that period. It seems to be more progressive than Bombay of today’s period, which is what I love about this book.

“There is that sense of possibility that I could be somewhere, that I could be someone”

He talks in this book about some real-life incidents. How when Partition happened, he had to leave. He was having a conversation with one of his friends who was a Hindi movie star, and Manto said, ‘If the rioters come won’t you save me?’ And the movie star, who was a Hindu, didn’t say anything. Manto was heartbroken and he ended up taking the steamer and moving to Pakistan.

After leaving Bombay he lived a truncated, difficult and unhappy life in Pakistan. He died in 1955, when he was pretty young, 42. He became increasingly alcoholic. He has written, ‘I’m a walking talking Bombay, I exist because Bombay exists’. It lived on in his memories, and in the form of this book.

He wrote it when he was totally broke and needed to drink. He would land up at the offices of newspapers and say, ‘Hey, I knew so-and-so Bollywood star, I can write about them’. He would sit there and write on a typewriter, write stories about movie stars, they would pay him and he would buy alcohol and get drunk again. That’s what Stars from Another Sky is about. It is these beautiful, real-life portraits of what the city was like at that time: progressive, glamorous, forward-looking, colourful, completely outsized. I feel Bollywood was more colourful then than it is now. That is what I found very interesting. People are eloping, coming back, beginning to shoot movies again. All kinds of things are going on and you can see why he’s completely enraptured by the city.

Where was Manto from?

He was from a Kashmiri who grew up in Amritsar. I was a big fan of Manto and I actually went and searched for his Bombay house, where some of these stories are written, where movie stars came to meet him. You see these portraits of them as shining Bollywood stars that he is enraptured by, but you also see them as people who he’s hanging out with, whom he’s trying to understand as a writer. He’s giving us these beautiful character portraits of people we’ve known and loved on-screen.

Mumbai continues to attract people from all over India, doesn’t it? It’s got Bollywood, it’s the commercial capital. It’s still attracting starry-eyed people, a bit like New York maybe?

Yes, it does. Like I said, even the waste pickers said they came with dreams in their eyes. And they were making a living by collecting what was left over by the city. Everyone can hope to have some place in this tiny city.

You said you feel Bollywood is less progressive now than in the 1940s. Compared to other parts of India, is Mumbai still quite an open-minded place?

Yes, certainly. For the purposes of this book, I got many writing residences, and I traveled in many parts of the world. I would say that Bombay is one city where women can still take public transport or walk around the city, at any point of the day or night. I live by a sea-facing promenade, and I see women alone walking along it at two o’clock in the morning. There’ll be tea vendors serving them tea, there’ll be masseurs giving foot massages. I never felt unsafe. There is someplace for everyone, and I think that gives people that confidence.

Cities like Mumbai give you the feeling that you can remake yourself as you would like. You came here as someone, but you don’t have to just stay in that place. You could end up in a very different place. Which is also the dream of the Ambanis, right? Even most taxi drivers will tell you, ‘Did you know the father started out in a gas station in Yemen? See now he owns that house.’ As I said, it is a somewhat unreal dream, but there are lots of people selling tea and driving cabs in this city looking up at that house.

One additional book you wanted to mention is a nonfiction book by Lisa Björkman, who is a political ethnographer at the University of Louisville. It’s called Pipe Politics and it’s about the city’s water politics.

I found the book hugely readable. There is this feeling that policy and all the workings of an almost non-working city should be so boring, but both with Kalpana Sharma’s book as well as this book they make it so interesting. One of the lessons for me as a writer was that we should not be afraid to talk about policy and think ‘oh the reader is not going to read if we talk about this.’ They are, and Lisa Björkman shows how. What she did with her book helped me with my book because I was talking about waste and looking at the city through its waste. She’s looking at the city through its water supply, as Kalpana Sharma is looking at city planning through Dharavi.

Pipe Politics is about the city’s water supply from colonial times to now. There are some incidents that are like movies just etched in my mind from the book. Nobody has a map of the water pipes, but Lisa Björkman gets one somehow and she has it in her house. One day, a BMC engineer comes to her house and rings the bell. She asks him what he wants, and he says, ‘Do you have that map?’ She says she does, and he asks if he can have it. She says yes, but that she’ll need some time to look for it. And he says, ‘No, no, we need it now!’ Then she looks out of her window and sees there’s a whole bunch of municipal engineers waiting outside. There’s a water pipe burst in the city and a stretch of street is flooding and they don’t have a map. Without it, they don’t know how to fix it.

It sounds chaotic. Does that mean you sometimes not have water in Mumbai?

No, we always have water in Bombay and we always have power. But she’s shown us how tenuous that is, the policy—how it all works, but almost doesn’t work, or doesn’t work, but almost works.

———————

Editor’s note: Saumya points out that 2021 is also the 40th anniversary of a very significant Bombay book, Midnight’s Children by Salman Rushdie, about a boy born at the midnight hour of India’s independence, endowed with magical powers to shape the history and destiny of India. Midnight’s Children won the 1981 Booker Prize:

Interview by Sophie Roell, Editor

October 12, 2021. Updated: October 19, 2021

Five Books aims to keep its book recommendations and interviews up to date. If you are the interviewee and would like to update your choice of books (or even just what you say about them) please email us at [email protected]

Five Books interviews are expensive to produce. If you've enjoyed this interview, please support us by donating a small amount.

Deonar garbage mountain, Mumbai

Deonar garbage mountain, Mumbai