You’ve chosen Jules Verne’s Journey to the Centre of the Earth.

Well, I think we all read that as children and I was most particularly excited by it a couple of years ago when I was in Western Iceland researching a big book on the Atlantic Ocean. I wanted to climb up the side of Snaefellsnes and look into what was, of course, the entry point for Verne’s explorers in Journey to the Centre of the Earth. So I did and I looked in and felt duly stimulated.

The book is a fantastic piece of science fiction – it’s basically about explorers who want to know what’s inside the earth and they go in via Snaefellsnes in Iceland and they find lakes and crystal caves and wonderful things and then, eventually, they are blown out back into Iceland by an enormous eruption. When it was written, in the mid-19th century, there was this debate between two groups of scientists arguing about the origins of the earth. The Neptunists believed that all rocks came about from the precipitation of sea water. The Plutonists believed that all rocks had been belched out from the middle of the earth. Jules Verne knew about this debate, of course, and rather sided with the Plutonists. So modern-day geologists can read it to see how fanciful and stupid people’s ideas about the earth were. Jules Verne got it completely wrong. It’s fun but foolish.

The Last Days of Pompeii by George Bulwer-Lytton.

This is an amazing book. It’s very Victorian and very pompous but absolutely accurate. It was written in 1835 and is a scrupulously well-researched piece of work about what it must have been like in Pompeii in the days leading up to the eruption. He builds brilliantly to the eruption of Vesuvius itself and describes the panic and how so many people died. Most of the people who were rescued were rescued by a blind woman called Nydia, because, of course, the blind can see when things go dark better than the sighted. When there are blackouts in New York you get the blind leading the way.

Were they really rescued by Nydia?

No, that’s a fiction. It was a hugely popular book in the 19th century and perhaps it seems rather arch nowadays but it is very touching. It didn’t teach us much about the science of volcanoes but it taught us the aphorism that man lives on this planet subject to geological consent which can be withdrawn at any time. I think this book brought home to an English readership how capricious and powerful volcanoes are. He’d done a lot of research – there is good geology in it. He spoke to Charles Lyle, one of the founders of modern geology, and he told him all about what must have happened at Pompeii.

The Crater by James Fenimore Cooper.

This was also written in the mid-19th century and it’s an adventure story, a bit like Robinson Crusoe. A chap called Mark Woolston sails across the Pacific and is shipwrecked. He lands on an island surrounded by coral reefs and it turns out to be volcanic. He uses the volcano to store fresh water and provisions and then the volcano erupts, forms a new vulcan’s peak, and he survives the eruption and climbs to the top of the volcano from where he can see passing ships and he is saved. It’s a rollicking good adventure story but it also tells us something about the volcanic origins of coral atolls, something that Charles Darwin wrote about in the Voyage of the Beagle. It was written around the same time that Melville wrote Moby Dick and these books are all of a piece. Americans were writing about the natural world.

Are we fascinated by volcanoes because they are dangerous and unpredictable?

I think so. I think that’s the reason we visit them so much as tourists. Earthquakes are altogether different because there’s not as much to see, but a volcanic eruption is like a gigantic waterfall or a huge storm and it’s very attractive, a visible manifestation of the power of the earth. In all three of these books the volcano is almost a living creature that we love and admire. When I was writing my book about Krakatoa I grew very fond of it. I mean, it exploded and had a baby.

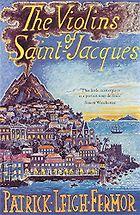

The Violins of St Jacques, Patrick Leigh Fermor.

I think this may be my favourite book in the world. I was asked to write the preface for the Oxford University paperback edition. It’s about the eruption of Mt Pelée in 1902 on Martinique. It sent this thing, a glowing cloud, a nuée ardente, ash and lava and hot air rolling down the hillside. It completely devastated the town of St-Pierre and there was one survivor out of a population of 30,000. It was the worst volcanic disaster of the century, until the tsunami of 2005. Before that it was Krakatoa in 1883 when 40,000 people died, but most of those died from the tsunamis that followed the eruption. Tsunamis were detected all around the world after that eruption.

Anyway, there was a ball being held in St-Pierre that night and, of course, everyone at the ball died, but the way it’s written is that he supposed all the guests survived and the party continued under the water. Fishermen say that a few miles out to sea when they are waiting for the fish they fancy they can hear music under the water.

Who was the survivor?

Louis-Auguste Cyparis. He was in prison and that’s what saved him, the only window was a narrow grating in the door. He was bad guy. A very violent man. I think he’d killed someone in a drunken fight. He went on to be a celebrity with Barnum and Bailey’s Circus. I love all Patrick Leigh Fermor’s books, but this is his sweetest.

Twenty-one Balloons by William Pène du Bois.

This is a children’s book and is fanciful nonsense but so charming. It’s about a balloonist who lands in the Pacific on Krakatoa, which is nonsense because Krakatoa is not in the Pacific. The island is all built of diamonds because there are diamonds in the volcano’s core, but, anyway, it erupts and they all have to escape. So the Professor, who was shipwrecked, makes 21 new balloons and they all fly away to safety. It’s a short, silly and utterly charming book which a generation of children, particularly American children, have enjoyed.

But Krakatoa is your main area of interest?

Yes. It sounds a bit pompous but I’ve written probably the definitive book on Krakatoa and at the moment I’m ash man of the week. Actually the ash clouds of Krakatoa changed the colour of the sunsets for years afterwards and prompted a huge explosion of art. It’s funny really – this eruption in Iceland has prompted a huge explosion of travel chaos but after Krakatoa painters all over the world were inspired to pick up their brushes.

Edvard Munch painted ‘The Scream’ ten years after he’d seen the skies over Oslo after the eruption in 1883 – those swirls of orange stayed with him. Everyone’s forgotten the eruption of Laki in Iceland in 1783 – it sent a gigantic cloud over Europe that killed cattle and scarred people’s skins.

Outside of Iceland?

Oh yes. There is never any damage in Iceland. Laki stands no more than ten miles away from Eyjafjallajökull, which is erupting now, and there’s Hekla as well. If Iceland decides to misbehave itself…

Do they set each other off?

Well, I’m fascinated by this and the geological community is trying to prove the connections. For example, the Denali fault in Alaska shifts and every time it shifts the geysers in Yellowstone National Park erupt more rapidly for three or four days. These are geysers like Old Faithful which erupts with very precise periodicity, every 56 minutes. But when the fault shifts, suddenly the geysers four thousand miles away erupt more rapidly and then they calm down.

The earth is like a great big brass bell and if you hit it hard it’ll vibrate for a long time and where there are cracks it will split. So, if you have an almighty earthquake, like the one in Haiti, it may well vibrate around the world. Have you heard of James Lovelock? The Gaia theory is that everything is connected and the earth is self-regulating. We all accept that the earth is heating up, so it opens the spigots a bit, lets out a lot of gas and cools itself down.

In 1816 after Tambora erupted in what is now Indonesia, there was snow in Washington DC in July. It blanketed the earth with cloud and Byron was so miserable in Lake Geneva in the sheeting rain that he wrote the miserable poem ‘Darkness’ and then Mary Shelley went to visit him and was so depressed she wrote Frankenstein. So, you see, volcanoes can have lots of strange effects.

So will the world cool down?

Well, if the others go off and flood the world with a huge outpouring of basalt and it goes on for four years it could have significant cooling effects.

Thank God. So everything’s fine then? We can go back to using proper light-bulbs?

Yes.

April 25, 2010. Updated: January 23, 2022

Five Books aims to keep its book recommendations and interviews up to date. If you are the interviewee and would like to update your choice of books (or even just what you say about them) please email us at [email protected]

Five Books interviews are expensive to produce. If you've enjoyed this interview, please support us by donating a small amount.