In your round up of the best 2018 music books, your first choice is Good Booty: Love and Sex, Black and White, Body and Soul in American Music by Ann Powers.

Ann Powers is the head music critic at NPR and I think she’s been working on this book for years. I’ve seen her do various readings from it at Pop Conference in Seattle. It’s the culmination of her life’s work. She’s a great feminist critic who always writes astutely about the intersection of gender, sex, race and power. And this book is a sweeping history of all of those things in pop music. To survey all of those things in one book is a really mean feat, so she breaks eras down into distinct chapters.

“She’s a great feminist critic who always writes astutely about the intersection of gender, sex, race and power.”

I particularly loved one about Britney Spears and Beyoncé and what she calls ‘cyborg pop’, about how they have both been depersonalised by the digital realm and how that’s worked to Beyoncé’s advantage, but perhaps less so to Britney Spears’ advantage. I also really loved her chapter on pop and the aids crisis and how pop retreated—or advanced, depending on how you look at it̛—into this fantastical zone. She talked about how many pop videos of that era used white space to create a fantasy that was removed from the world. There’s a lot of observations and analyses like that in the book that stuck with me.

There’s a lot here about pop music as rebellious and transgressive—a means of fighting back in contexts of oppression. She describes pop music as being a “conduit for both joy and pain”. But when we’re talking about eroticism in music, does she engage with the nastier elements of the music industry in terms of who’s actually controlling the amount of sexual imagery and objectification of artists?

She takes a much more artist-first approach rather than an industry-first, but there is a bit in that when she writes about how the entertainment complex dehumanised Britney Spears. But a lot of people—and I am among them—think that one of Britney’s best albums is Blackout, which was made in the midst of her breakdown and which wields cyborg voices and other depersonalised techniques against the media.

Next on your list is The New Analog: Listening and Reconnecting in a Digital World by Damon Krukowski. Can you tell me about the arguments he’s making here?

He’s basically talking about how we hear music now: the platforms, the equipment, the cultural environment. He’s a very unique thinker. He’s in a band called Damon & Naomi and was in the legendary indie-pop band Galaxie 500, so he’s writing as both a practitioner and as a theorist. Although it’s advanced, it’s very comprehensible. It’s one of those books that makes your brain fizz for a few days after you’ve read it.

There’s a rich combination of psychology, acoustic science, and audio engineering. You mentioned the poor compensations for artists with streaming services. What other things does he identify as the price that we pay for switching to digital?

He applies the distinction that is made in the studio between ‘signal’ and ‘noise’ and does it in a philosophical way to talk about what’s valuable about what we’re hearing and what’s not valuable and how one crowds out the other.

He writes that “the time it takes to listen to music is now in shorter supply than recordings.” If you take classical music recordings, it does seem like there are so many different conductors, so many different orchestras; there’s a real proliferation of music. The amount of attention you can give to any particular recording seems compromised in the digital age.

Totally. But something else that I liked about his approach was that it wasn’t just pessimistic. It’s very easy to write an op-ed damning Spotify. I agree with many of the charges against it, but Krukowski recognises, as anyone sensible does, that you can’t put the genie back in the bottle. It’s more pragmatic than easy polemic.

Absolutely. Could you tell us a little about your own listening habits as a music critic? If you’re going to write a piece on an album, what are your close listening practices?

It depends how long the review is and how far in advance you have the music. Typically, if I’ve had an album for a while, I might have listened to it 60 times by the time I come to write a long review of it. But if I’m writing a 250-word review of it for The Guardian’s weekly music section, I might just have heard it three or four times at my desk. But however I’m doing it, the end process is always the same: if there are lyrics, I will annotate them and pick out familiar themes, then I do an annotated listen, listening and typing ideas about the different sounds and segues in quite a stream of consciousness way. Then I see which songs might fit together in a discussion or that you can thread into a compelling argument.

“It’s one of those books that makes your brain fizz for a few days after you’ve read it.”

In terms of casual listening, I have a record player but because of where it sits in the house, I tend to listen to a particular kind of music on it. It’s in the living room so it’s usually quite relaxed or background music. It has a specific function. I still have an old iPod that is creaking on, thankfully, though I have found that, especially since iPhones got rid of the headphone socket, I have been using wireless headphones on my commute and been forced to listen to Spotify and Bandcamp. I try and use those service for discovery. Once I’ve listened to something a few times, I usually buy it because I like to have the mp3. I don’t trust the cloud not to wipe all my music someday.

Your third book is All in the Downs: Reflections on Life, Landscape, and Song by Shirley Collins.

Shirley Collins is a legendary English folksinger who was one of the leading voices in the UK from the 1950s through to the 80s. She really pushed English folk song in interesting directions but was similarly keen on preserving its integrity. She was right in there with people like Ewan MacColl, who she is brilliantly scathing about in this memoir.

She writes really astutely about English folksong but also the interpersonal details of that folk scene. There’s a lot of love triangles—I think her second husband was cheating on her with somebody in this scene. Shirley goes to perform and this woman is wearing his jumper and she knows that he’s cheating on her. She suffers from a psychological condition called ‘dysphonia’ and loses the ability to sing, both physically and psychologically. So, she goes and works in an Oxfam in Brighton and in a job centre for, I suppose, something like thirty years. But somebody tempted her into trying to sing again and she did a couple of concerts five years or so ago, which led to her releasing a new album called Lodestar on Domino last year. This led to a revival of her music and renewed appreciation of her.

I’ve interviewed her; she’s eighty-three, and she’s absolutely fantastic. She takes no prisoners, she’s really funny, and she is not interested in upholding the legendary figures of folk music. It reminds me in a way of Viv Albertine’s memoir where she doesn’t want to stoke the legacy of people like Johnny Rotten. She just tells it how she saw it.

Does she go into detail about how she gets her voice back? Was it just waking up one day and being able to sing again or was it a sustained therapy-led process of grappling with those demons?

I don’t think she gets therapy. Part of it is having a lot of people believe in her, basically, and challenge her to do concerts. She talks about going to the rehearsal to sing one or two songs at the Union Chapel as part of someone else’s concert and really thinking that she wouldn’t be able to do it, and being surprised that she could. It’s to our great benefit that she could. I hope she makes many more albums.

How would you rate Lodestar as an album compared to her older back catalogue?

I can’t pretend that I’ve listened to all of them, but I thought it was absolutely wonderful. It’s really hypnotic and her voice has got such a fantastic grain to it as well. We often talk about how great older men’s voices sound but, just because there are fewer older women of that generation who are still participating in music, we have less of a fully rounded conception of the many many different ways that an older woman’s voice can sound. I thought hearing her all low and strident on those songs was really exciting. But I also love the music she made with her sister Dolly: their 1969 album Anthems in Eden is really fantastic.

And her writing style? You said she was very funny and she has a very strong eye for detail.

Yes! She writes about men who were really threatened by her. She was always protective about what folk music was and what it wasn’t. She went to this night where it was billed as a folk night, but actually they were playing skiffle. She was really annoyed and so she crossed it out on the poster with her lipstick and then the promoter of the night pointed a knife at her.

“She takes no prisoners, she’s really funny, and she is not interested in upholding the legendary figures of folk music.”

She also writes brilliantly about masculinity and what she finds attractive. It shouldn’t, but it feels delightfully subversive for a lady in her eighties to be writing about how sexy she found Alan Lomax and how sexy she finds Morris dancers. It really opened me up to the beauty of things that I never really contemplated or that I had just thought of as a bit parochial—I’m from Cornwall and so I’ve grown up seeing a lot of those traditions, but they always seemed a bit archaic. But to read someone valuing it as a really vibrant art form does make you see it differently.

Next, you’ve picked Night Moves by Jessica Hopper. Can you tell me why you’ve chosen this one?

I love Jessica Hopper’s writing. She is a legendary critic who started out as part of the original riot grrrl scene. She had a book out a few years ago called The First Collection of Criticism by a Living Female Rock Critic, which is a very provocative and mostly true title. There are some out-of-print examples from the 80s, but to all intents and purposes, she can stake that claim. That book collected her work from her zine days through to the work that she’s doing now for Pitchfork, Spin and Buzzfeed and all sorts of places.

Night Moves is a different kind of book. It’s a memoir of a very specific time—which I think is the best type of memoir, like Steve Martin’s Born Standing Up. It was adapted from the diaries of life in Chicago in her mid-to-late twenties; she still lives there. It’s just on the cusp of modern technology; she and her friends have to go to the library if they want to use the internet. It’s just a really joyful portrait of cycling around the city, going to punk shows, seeing gentrification happening and being aware that you’re part of it, mourning what’s disappearing, but also valuing the new.

“It’s a memoir of a very specific time—which I think is the best type of memoir.”

The age that she is in the book is the age that I am now. She says something like, ‘If at 29, I was not living my most hopeful politics then what am I doing?’ It’s a good thought to keep in mind. It’s a pretty breezy book, I read it in probably two or three train rides, but if you like her work and have any interest in the DIY punk scene, then it’s worth reading.

It’s stylistically quite unusual as well. You mentioned that it’s based on diary extracts, but they’re not in chronological order, are they?

No, they’re not. I think that gives it a really nice immersive feel. If it were in chronological order, you might expect some narrative payoff. You get to know her friends because of the assemblage of anecdotes.

I read a lot of memoir and I like it, but I often think: how does somebody know how to write the end of their memoir? When you’re Shirley Collins, you’ve lived a very full life and the ending is clear, but if you’re writing about your twenties or thirties, how do you conclude that? An ending seems finite, but obviously your life isn’t over. Sometimes I think it can strike a false note, and so the bricolage of memories in this book—not to sound incredibly wanky—was really delightful, I thought.

There is a comment on the front cover of the book itself by Emma Straub which suggests it could be classified as autofiction, a genre in which the boundaries between autobiography and more fictional reflections seem harder to draw. Did you get that impression from the book? Are there elements that seem fictionalised?

I did some reading interviews with her and I think she said there are parts of it that are maybe styled up or slightly changed but there is no indication in the book of where those boundaries lie. I didn’t read it as a wholly truthful diaristic photocopy, but it didn’t seem falsified. It seems mythologised, but everyone’s memories are mythologised. I found it a much more straightforward read than Crudo by Olivia Laing, which I did enjoy but found slightly baffling in parts.

Would you say that in these vignettes of Chicago nightlife, music is the central pivot around which all of the reflections are happening?

Totally. She’s always cycling between several shows in one night, or going to dance parties, or DJing herself. Even when an interaction isn’t directly orbiting music being performed or listened to, everybody who’s in her scene and everything that’s to do with her life is all about music.

There’s a way that you can professionalise in your mid-to-late twenties and lead a fancier life, but these are people who are really dedicated to it and want to be fully immersed in it whatever the cost of that is.

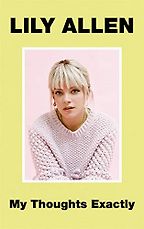

Your last book choice is My Thoughts Exactly by Lily Allen.

It is such a no-holds-barred book. We know that she’s a great writer because of the songs she has written since her first album, but I thought her capacity for self-reflection and for seeing the patterns that have defined her life and maybe sometimes led to a degree of self-sabotage was really arresting.

“It’s that cutthroat, repulsive prizing of money over morals and the well-being of artists.”

You could equally read it as history of tabloid culture in Britain in the twenty-first century. She writes about how her life was invaded by the tabloids when she was barely out of her teens. The way that they distort the truth of her life ends up feeding back into the way that she lived it. She alludes to the phone hacking scandal and how very personal things ended up in the papers without anybody having told them. The way that the tabloid media sought to gaslight her over the course of her career is horrifying.

As well as tabloid culture, it seems especially damning of some of the more toxic aspects of the music industry. She mentions sexually predatory record executives.

Yes. She talks about being allegedly assaulted by somebody who has a close relationship with her record label. Perhaps she talks about this in interviews rather than the book, because it might have been legally problematic, but she claims that when she tried to raise it with the label, their response was essentially, ‘he’s more valuable to us than you are, so we’re not going to do anything about it’. It’s that cutthroat, repulsive prizing of money over morals and the well-being of artists.

So those are your 2018 music book highlights, but you mentioned to me that there are music books that have made important strides but that you haven’t had chance to read yet. Would you mind saying a bit about those?

I’m planning to read Dan Hancox’s book Inner City Pressure: The Story of Grime over Christmas, and I’m excited to read Margo Jefferson’s On Michael Jackson that was recently reprinted. I’d like to read Jeff Tweedy’s memoir and also the Beastie Boys Book – I love the way that has been put together. I also really want to read K-Punk: The Collected and Unpublished Writings of Mark Fisher, the critic who died last year. But Dan Hancox’s book especially, I feel bad that I’ve not read it yet.

Five Books aims to keep its book recommendations and interviews up to date. If you are the interviewee and would like to update your choice of books (or even just what you say about them) please email us at [email protected]

Five Books interviews are expensive to produce. If you've enjoyed this interview, please support us by donating a small amount.