Before we get to the books you’ve recommended, what do you feel someone visiting Venice needs to know about the city and what drives it? Is it the phrase that comes up in your book, ‘com’era dov’era’?

That’s an awfully good phrase to hang it on, in that I don’t think there is another city that has remained as much as it was, say, 150 years ago. That’s unusual and it’s because of the extraordinary topography in that Venice has no suburbs. Almost every other city of any importance or size that one knows has a centro storico and then either there’s a downtown, or there are suburbs that dilute.

The phrase com’era dov’era gets coined when the campanile of San Marco falls down in 1902 and the Soprintendenza say, ‘It’s got to go back exactly the same, we don’t want anything different. It’s got to be in the same place, looking the same.’ So, despite the fact that Augustus Pugin and William Morris and everybody else was horrified by what the Italians were doing to Venice in the late 19th century, not much happened and one is still looking at a late 18th-century view of the place. It’s the most extraordinary thing and why it has been worth doing com’era dov’era.

What I wanted to do with my book, I suppose, is get past the crowds and the bad effects of mass tourism. There are lots of good effects, mass tourism is keeping Venice going—and has done for about 300 years. It’s not new, but people do come back and say ‘I had a horrible time. It was expensive, it was filthy food, and we couldn’t move anywhere.’ Occasionally you do find yourself inadvertently walking to the station at five o’clock in the evening or going along the Riva degli Schiavoni in front of the Bridge of Sighs at midday, elbowing your way along shoulder to shoulder, and you think, ‘This is absolute hell on earth.’ I was trying to help people find, it’s a bit corny to say the ‘real’ Venice, but at least a Venice that’s as unaffected by change as one could hope to find.

Of the books you’re recommending about Venice, what were you trying to cover in your choices?

Venice is quite filtered, it’s quite interpretive. Probably, as much as any city one knows, it’s seen through a literary lens. That’s true of London and New York and other cities as well, but there’s a lexicon of writing about Venice, partly because in modern times—say post-1550—it’s been the most service of economies. Venice’s heyday in the Middle Ages had been eclipsed by the end of the 16th century.

Venice had been the second most populous city in Europe. Paris was the biggest, but Venice outdid London, Rome and other early medieval European cities in population even though its actual size was so small. Then there was a seismic change as trade moved from the Silk Road and the route to the East and spices to the New World and Venice’s whole raison d’ être began to fall apart. Suddenly Cadiz was more important. At the same time, Venice also lost out to the Ottoman Empire. Its sea empire, the ‘Stato da Màr,’ which controlled the Adriatic and Eastern Mediterranean—and included a lot of islands, Cyprus and unofficially Corfu—began to fade.

“I was trying to help people find…a Venice that’s as unaffected by change as one could hope to find.”

By the end of the period, Venice was more of a place to visit than a commercial or certainly a political center. From the beginnings of the Grand Tour at the end of the 16th, when people like John Donne went there—allegedly as a spy—people were going as tourists. They went to find out what the Renaissance was as seen there. They went because it was lovely. It has always been an extraordinarily good place to visit. It laid out its wares very generously to Northern European tourism. It still does. It’s very unusual as a city in that you never feel you’re intruding. It’s easy to consume and that’s very exciting. Consequently, it was consumed, and a lot of people wrote about it. Perhaps because of that, it became a cradle of ideas in all sorts of areas. John Ruskin is a good example. In the 19th century, he is trying out an idea which is a proto-socialist, anti-industrialist diatribe.

As you’ve mentioned him, let’s talk about his book first. It’s called The Stones of Venice and the edition you’ve chosen is edited by the British travel journalist and author Jan Morris.

Yes, it’s a neatly filleted version of The Stones of Venice. So Augustus Pugin had already written a book called Contrasts in the 1830s where he has two pictures: one of the medieval city and one of the new city. The new city is full of factories and classical, pedimented museums and town halls; the old city is Gothic towers and spires, and crocketed finials and Gothic-ry. The message is very, very clear, which is that the medieval world is a world of craftsmanship, personal fulfilment, independence, spiritual probity and commercial honesty that finds a language, a physical manifestation, in the Gothic.

Ruskin, writing 15 years later, is part of that same group of thinkers who are obsessed with medieval ways. William Morris, as well, is tackling that. Ruskin says that even to work on classical buildings must have been a diminishing experience. He writes about how awful it must have been to carve the dentils on a cornice (the little teeth that go along it) because all creativity would be killed by doing this job. Instead of a mason carving bosses in the shape of leaves or carving animal heads or wonderful gargoyles who look like your school teacher, everybody is reduced to this mechanized work.

Ruskin is also making a moral religious point that saying goodbye to the Gothic is saying goodbye to God, the idea of good, and moving into the world of Mammon. Ruskin ties up the idea of the neoclassical and the Renaissance with the Industrial Revolution and an end to goodness, for want of a better word. So Ruskin writes with venom, really, about the Renaissance. He calls it evil and sinister. The Baroque is abhorrent, a monstrous wrongdoing to mankind in his mind. He’s the most intemperate man you could possibly imagine and absolutely absurd. (He was also a tricky husband to Effie, whom he was married to. He was horrified, it is said, to find pubic hair because he’d only ever seen a Greek statue of a woman. He assumed everything would be white and marbly).

Get the weekly Five Books newsletter

But he was a marvelous painter and an amazing thinker. His ideas were behind the Natural History Museum in Oxford being built, and the O’Shea brothers carving those extraordinary capitals. Someone would bring a plant from the botanical gardens in the morning, and these Irish masons would carve that plant into the building. A lot of those ideas about the Gothic, Ruskin cuts in Venice. He spends a lot of time drawing and measuring. He’s very careful, trying to tabulate the world. He has a lot of ideas about when arches became Byzantine, and when they became Romanesque. He is quite often quite wrong. But the idea is a powerful one, that Venice, as a Gothic city, is an act for good.

His ideas then have a tremendous life in diaspora, particularly around Britain. You get buildings like Templeton Carpet Factory in Glasgow, the Meadows building at Christ Church, or St. Pancras station in London. There are a number of buildings that use the language of Venice in English architecture. It is a political thing, it is saying, ‘This is how you do good.’

Reading the whole of The Stones of Venice is unbelievably stiff and solid, but this edition is one of two or three very good, filleted versions of it with commentaries. It’s got such a bearing not just on how you read Venice, but on how you read our own built environment. There’s the Gothic Revival, which turns into the Arts and Crafts movement. It’s at the root of a lot of socialist ideas. William Morris is writing News from Nowhere at the same time as he is trying to help campaign for Venice to be looked after properly. It’s a powerful document. It’s a book that says Venice is not just a beautiful playbox, it’s also a crucible of ideas that have had a massive effect on Northern European culture and social life.

In what sense social life?

The shape of 19th-century paternalistic care is Gothic and a lot of that Gothic comes from Venice. It also has quite a big effect on the art world, and just physically in that there are a lot of buildings in Manchester, Leeds or London, or indeed in northern France and in America that quote Venice. It’s not the only language that comes out of Venice. Palladianism also comes out of the Veneto and Venice, and that has its own contrasting series of influences, but that’s a separate thing.

Let’s turn to the history book you’ve chosen. This is Italian Venice: A History by Richard Bosworth, who is a senior research fellow at Jesus College, Oxford. This is about modern Venice, I believe, after the fall of the Republic in 1797.

The end of the Most Serene Republic of Venice happens when it cedes to Austria. We have Napoleon, Austria, and Italy, all foreign powers—and certainly Venice sees Italy as every bit as much a foreign power as Austria, possibly even more. It’s a bit of history that’s probably less well handled in most guidebooks because it’s quite complicated, but it has quite an effect on what the city looks like. There’s the filling in of some canals, the straightening of some roads, the building of some fairly gloomy social housing. There’s a Teutonic effort to rationalize the city, though if ever there was an absolutely futile project it would be trying to make sense out of Venice.

The book also deals with the fact that Venice, as well as being fabulously rich, was piss poor. The poor in Venice were much poorer than the poor in other places. There was very little running water and not much in the way of facilities. The fishermen and people who operated Venice were living in very low-quality, medieval accommodation, sharing a well. Life expectancy was low and I think life was brutish and short. This book is very good on the extent of urban poverty.

It is also very good on the still current quite big issue, which is migration out of the city. The whole world is full of people moving into cities, but when you get highly developed as Venice did you move out. That probably starts in earnest after the Second World War, but it had happened before. There was the building of Mestre, and then of Marghera, the chemical port.

“There’s definitely a whole world of Venetian gloom, but it seems absolutely joyous to me”

The book introduced me to an amazing man called Giuseppe Volpi. He was called the ‘Last Doge’ and I’d never heard of him. He was a businessman of terrific acumen and was made Count of Misurata by Mussolini. He also became governor of Tripolitania, which is Libya. He set up the Venice Film Festival and the Biennale and massively changed tourism in Venice as well as setting up a lot of industries. So he set up Marghera, which is both negative in that it has caused terrible petrochemical pollution, but also provided employment. He had a huge effect on changing the place.

I found Italian Venice absolutely brilliant. It is a very, very good book to read when you’re there. Some of the stories! One of the things that’s mentioned in every guidebook on Venice is Molino Stucchi, this great big Gothic behemoth of a building on the end of the Giudecca. It’s now got a Hilton in it and, on top of it, there’s a Nutella bar. I don’t know why, but I wasn’t allowed to mention the Nutella bar in my Venice guide. It seemed to me one of the things that everybody would be most interested in. I’ve never been to a Nutella bar before, but if you like Nutella…But that mill was built by an Austrian to feed Venice, and he was beset by a series of terrible personal misfortunes. Eventually, it burnt down, he died, everything went wrong, and it sits there as a great ghost town factory. That end of the Giudecca has also got the woman’s prison and one other prison. It’s not a surprise that it’s the most communist of Venice’s sestiere because it’s quite rough.

That’s why I would recommend Bosworth’s book. He writes brilliantly, it’s not humorless, and it deals with some of the nitty-gritty of population loss, of poverty, of economic reforms and changes.

There are also some big political events. There is the revolt against the Austrians. Then there’s the acceptance of Italy and the effect of Italy coming in and extraordinary stories about the wars, both the Great War in which there was some shelling, but Venice was used for R&R, and the Second World War, when Venice did resist fascism for quite a long time but then gave in to it. There’s the terrible end of the ghetto and the effect of Nazi rule on Venice. You might say Venice escaped lightly, but it was still massively significant, which, in a way, takes me on to the next book.

This is the thriller you recommended, The Girl from Venice by Martin Cruz Smith.

Yes, it’s a thriller that’s set in the lagoon and in Venice and northern Italy, towards the end of World War Two, in 1945. It begins with the murder of a German officer and it’s about a Jewish woman who is rescued by a fisherman who hides her. It’s an extraordinary adventure story. The fisherman’s brother is a rising star of Fascist Italian cinema and is a great favorite of the local Gauleiter but also of Il Duce. So one brother is basically a partisan and the other is an apparatchik of the regime.

It deals with this extraordinary moment in history. Things go badly at beginning of the war for Mussolini and eventually the king, who is sitting in the Villa Ada in Rome, says to Mussolini, who’s living in the Villa Torlonia down the road, ‘Could you come and see me this afternoon? Don’t wear a uniform.’ Mussolini’s wife asks, ‘Why aren’t you wearing a uniform darling?’ And he says it’s because his majesty said don’t wear one, which is a bit odd, but never mind. So he goes down the road. And the king says, ‘Listen, things didn’t go well for you in parliament yesterday.’ They had gone very badly. But Mussolini said (a bit like Boris), ‘We’ve got a majority. It’s alright.’ And the king said ‘No, it’s not alright. It’s no good. And this is going to play badly for us all. So I’m afraid you’re going to have to stand down now.’ And Mussolini says, ‘Okay, well, I’ll just get my driver.’ The king says, ‘No your driver is already gone. The reason I asked you to wear ordinary clothes is you’re going to be going by ambulance. And he is sent out of the back of the Villa Ada and packed off and is disappeared. Later, he gets reinstated after a couple of satisfactory German operations. The worst bits of Nazi activity in Italy are from this second manifestation of Mussolini, where he’s hardened up and is under German orders. That’s when the ghetto is emptied, that’s when in The Garden of the Finzi-Continis, instead of being told they can’t be members of the tennis club, the entire family is deported and killed. It’s also where things go drastically and appallingly wrong for Mussolini and, in due course, he is shot against a wall and hung up outside the Esso garage with his girlfriend Clara Petacci.

The Girl from Venice is a brilliant read. It’s a very good story. If you were, for example, going to Venice in the summer, and you wanted to sit on the Lido for a day and read a book, I would read that. You’d look out onto the lagoon from your lovely cabana. And you’d think, ‘Bloody hell, that was what was going on here.’ It’s a novel, but it’s very well dressed. I’m not a great thriller reader, but I thought it was wonderful.

Let’s move on to The Architectural History of Venice by Deborah Howard, which seems to go right from the beginning, the founding of Venice.

It is a most erudite, solid and full guide to the buildings of Venice. If you are more interested in buildings than my book tells you, it’s the one to go for. She has all the facts.

The architectural history of Venice is extraordinary, not least because it’s built on water. The whole construction of these buildings, the number of piles that were built to make the foundations! So you drive the piles into the mud. Then, on top of that, you set a series of huge, crisscrossing larch planks, which make a raft called a zattera. When you’ve got this semi-stable foundation, you’ve got to build as thin and as light as you possibly can, because the building is sitting on a load of old sticks. So the walls of most Venetian buildings are terribly thin.

There’s a 6th-century Roman description of Venice, of a fishing community on an island where everyone is living on alder poles in houses made of rushes in similar poverty. It’s a good foundation myth of people of all estates living equally side-by-side that is absolutely central to the idea of Venice as a republic. Venice’s ruler, the doge, was unbelievably disadvantaged by his role. It was very arcane and famous for the dotty way he was elected, with 20 people choosing 100 and 100 choosing six, and six choosing two and two choosing 40 and 40 choosing 20. They go from one vast room to another and, eventually, I imagine the name of the person somebody wanted in the first place pops out of a hat. But theoretically, people didn’t have such a vested interest and in any case, their rule was often short-lived because it was such a gerontocracy.

But those early buildings are, I suppose, genuinely vernacular, built of what’s around, which wasn’t much. Later, bricks had to come from Treviso or somewhere on terra firma and timber had to come first from the pine forest along the coast and from oaks in the hills and then later from further round into Istria. The numbers are astonishing: 500,000 piles were needed to make San Marco and Santa Maria della Salute had millions of acres of forest denuded to make it stand up.

Then you make a damp course of Istrian stone, which is incredibly impermeable marble. And as long as the water goes up and down on that, the water doesn’t get into the building. Then you can build with brick on top of that. That’s one of the problems. One of the much-vaunted threats to Venice is the rising water levels which would take the mean water level above the Istrian stone damp course in old buildings. That’s why everybody is concerned about that.

“An awful lots of what’s most exciting about Venice is in churches”

Deborah Howard’s book deals with not only how things are built, but how the early buildings were very influenced by Venice’s initially belonging to the eastern half of the Roman Empire (when the Roman Empire splits, Venice becomes part of the Exarchate of Ravenna and is answerable to Byzantium) and turning to Constantinople, both culturally and politically, rather than to Rome. One then deals with the effect of Byzantium, whether it’s in terms of mosaic and gold or just the nature of the arches and stilted arches, and then the Gothic develops.

Venice is conservative all the way through the Renaissance. It’s very slow and resentful about change. The first Renaissance building, probably by Mauro Codussi, is San Michele on the graveyard island and is 70 to 80 years after Donato Bramante’s building in Rome. It’s even longer after Giotto and Filippo Brunelleschi are building in Florence.

One of the tropes is that Venice looks backward because it doesn’t have a past. By 840, a lot of the parishes in the middle of Rialto were already decided, but it doesn’t have an ancient history. So there’s this overriding desire to get the credibility of ancientness. There’s this idea of spolia—stone saved from other buildings—and borrowed antiquity. Take the porphyry sculpture of the Tetrarchs, brought back from Constantinople, probably in the Second Crusade, and embedded into San Marco—as are all sorts of panels and discs of porphyry and other precious stones. Even St. Mark’s remains are famously rescued from Alexandria. It isn’t actually the cathedral until about 1807, but the ducal chapel.

So San Marco has this strong Byzantine flavour?

Absolutely. It’s dark and numinous and glittering and oriental. Even Ruskin, who loved it more than his mother, hates the cresting that goes around it. He’s full of frightful fury about various people’s work to it. But it’s right up there with Hagia Sophia as one of the great Byzantine, early Christian buildings.

If we’re talking about the architectural history of Venice, do we need to mention Palladio?

When I said that the Gothic was the great export of Venice, probably more unique to the Veneto and Venice and equally pervasive globally, is Palladian classicism. Andrea Palladio was actually called something quite different, but was adopted by a grandee of Mantua, who called him Palladio after Pallas Athena because he was such an amazing god of drawing. He was a stone mason, as was his father, and had these extraordinary ideas.

Italy was the cradle of humanism, particularly in Padua and Rome, and the buildings of ancient Rome were being unearthed. People were trying to work out the lost wisdom of the ancients and the architecture was under their feet. Raphael famously recorded the paintings of the Domus Aurea in Rome. Palladio looked at these emerging buildings and, in the early 16th century, developed a new language of classicism which was of huge significance.

Sebastiano Serlio had already been tabulating how the orders were used and making rules and people were aware of the work of Vitruvius, who was the first century architect/writer who wrote about defense, beehives, constructing bridges, and drainage. Palladio took this and applied it initially to villas on terra firma, then on a series of church facades in Venice: the Redentore, San Pietro di Castello, San Francesco della Vigna and posthumously—allegedly—the Zitelle and various other smaller works. For example at the Carita, the nunnery that was turned into the Accademia, there’s a cloister inside that was done by him.

One of his particular tricks is superimposing one pediment on another, so you end up with two entablatures, one in front of another. But the main thing is that he’s building churches with temple fronts. He’s using the language of non-Christian Greece and Rome to express church architecture. It’s a big dramatic change, and it’s why it comes late to Venice. Then it goes everywhere. After Villa Rotonda appears, you get buildings like Mereworth Castle in Kent, Chiswick House in London, Monticello in Virginia and George Washington’s house, Mount Vernon. I suppose because Venice is a republic, Washington espouses Palladianism as a language of this new country and it takes off. It makes the English country house and is woven back into Dutch and French neoclassicism, which up to then had been based mainly on Dutch copybooks.

So Palladianism is for some people the most and for others the second most important architectural export.

What about the Venetian artists, Mantegna, Tiziano, Giorgione etc. is there a lot to see of their work in Venice?

There’s not much Mantegna, Giorgione’s Tempest is in the Accademia as are several Titians. The Accademia is a very good museum because it hasn’t got much in it. The best Titian in Venice is this extraordinary, bright red altarpiece in Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari, which is a Dominican, mendicant order Gothic church on the Dorsoduro in St Polo.

It does occasionally rain in Venice, so you do need some indoor excursions. For sheer artistic passion, I’d recommend the Scuola Grande di San Rocco, which is a bizarre series of Tintoretto paintings. The scuole were guilds, either of craftsmen, or sometimes just of rich tradesmen, who would gather together to do good and get power. They built assembly halls to work in and they were big focuses of non-ecclesiastical resource. They were nominally religious, not either parish churches or monastic orders, but rivals to churches in their spending. There were chapels in each one of these scuole. San Rocco is this extraordinary narrative of St. Roch and the paintings are huge, 20 yards by 15 yards. They’re full of wild, dramatic chiaroscuro and extraordinary blown-up perspectives. You look at them by sliding around the floor with a mirror on a school dinner trolley. It’s absolutely brilliant.

Five Books interviews are expensive to produce. If you're enjoying this interview, please support us by donating a small amount.

The absolute other end of paintings to go and see would be the Carpaccios in the Scuola di San Giorgio degli Schiavoni, which is behind San Marco. They’re almost genre pictures because they are pictures of Venice as it was in 1500. There is this extraordinary, overriding oddity about Venice, which is that because it’s so unchanged whether it’s in Carpaccio or Bellini, Guardi or Canaletto, you’re looking at paintings with a costumed cast that could be you. That’s such an exciting thing. Obviously, things change a bit: the gondolas used to have covers, now they don’t. But, in general, many views, whether medieval or later, are recognizably unchanged.

The Correr Museum has also got a lot of wonderful paintings in it. Napoleon was very, very pleased to have got this great bauble, Venice, for his empire and called San Marco the greatest drawing room in Europe. He knocked down the Church of San Frediano, which faced San Marco, and built himself the Ala Napoleonica. It’s a whole series of Empire rooms and big staircases, charmless but grand and with wonderful things inside.

Another extraordinary museum, less for paintings but for odd things, is the Naval Historical Museum, which is up by the Arsenale. It’s an extraordinary collection of model boats and shells. One of my favorite things is a series of working drawings for First World War battleships. They’re huge, complex, and very neat, and they did all this without a felt pen. They must have been waiting for the ink to splotch at any moment, and for the whole thing to be wasted.

But I think that whereas Rome is about sculpture and big private collections an awful lot of what’s most exciting in Venice is in churches.

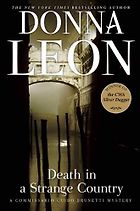

Let’s get to your final book, which is a book in Donna Leon’s Inspector Brunetti crime fiction series, Death in a Strange Country.

These are probably the most read books set in Venice. She’s written about 25 of them. They’re all exactly the same. It’s always terribly hot or terribly cold. They revolve entirely around Brunetti, our hero, going back for lunch with his wife, with whom he is very much in love, and having a quick brandy while she does the washing up, and then stomping off back to the Prefettura to do some essential police business.

I think it’s really easy to go to Venice and not believe anything’s happening there. I think what’s exciting about those books is that they give you a very believable, compelling idea of something that is happening. Italians love uniforms and there are a lot of policemen and different types of police launches in Venice. She brings to life the idea of civil Venice, and to a degree also of a darkness and a world of crime, drugs, prostitution, human trafficking and all sorts of the world’s ills which don’t exclude Venice.

Brunetti is a most sympathetic hero who one can only identify with, with his children and his wife who is an academic, a Jane Austen scholar or something highly convincing like that. The children are busy writing their homework, while he’s sorting out gory crimes. There’s also the most marvelous lady, a Miss Moneypenny figure who is a constant through the books, who’s always tutting and letting him in to go and see his superiors. There’s not an overarching dramatic narrative as exciting as the Cruz Smith book, but these books do immerse you in Venice. She’s American, but her complete fluency in the ways of Venice allows us to dive in with her.

I like mysteries so I’ve read quite a few of Donna Leon’s books over the years, just because there are so many of them. When I was reading your travel guide to Venice and you mentioned the name of a place, I kept going, ‘Oh, yes, I know that name. Brunetti is always walking along there.’

In coming up with these books, I was trying to provide a series of overlays, each one of which explains Venice a bit more. It’s a city that’s got a very good back catalogue of books that you can layer on top of it, all adding another bit, and I’ve tried to do that with all the books I’ve chosen. It’s the idea that you’re enriching the place.

I didn’t choose Death in Venice because it’s too jolly obvious, but there are all sorts of miserable books out there. There’s a big trope of Venice as depressing and black and gloomy. I’ve been every week of the year and I just can’t find it. I’m well aware that people do. There’s definitely a whole world of Venetian gloom, but it seems absolutely joyous to me. I’ve been sad there, but in quite a nice, picturesque way.

Another very good book I read was about two men who want to be members of the Venetian aristocracy, Venice’s Intimate Empire by Erin Maglaque. There was a book called the Libro D’Oro, which listed the nobility. After the serrata in 1297, no one could rise to join Venice’s Grand Council anymore. One of these men is the illegitimate son of a noble family, whose family are trying to get him legitimacy so he’s on the list. The other is a tradesman’s son, who is almost rich enough to get onto the list. One ends up being the governor of Candia, which is Crete, and the other is the governor of another town on the mainland, in Istria. The tradesman marries a local princess, and consequently does get elevated. The other one marries a servant girl who he loves, which makes it even harder for him.

It’s the idea of the Venetian Republic as a complicated world. We don’t get it now because we’ve had universal suffrage for so long, but people longed to be an elector. In Venice, if you weren’t on that list, you didn’t have a vote as to who would be Doge and, as such, preferment was unlikely to come your way.

If somebody wants to read about the Venetian Empire is that a good book to start with?

No, there are lots of more general ones. John Julius Norwich, A History of Venice, which is more than 700 pages long, is very, very good. It’s probably the most thorough of all the histories. It touches on that period, and some of the issues around social mobility and the concentration of power and, also, the feeling of an empire. Now we just see Venice as a beautiful town. We don’t see it as an empire anymore because it ain’t, but it was one.

Five Books aims to keep its book recommendations and interviews up to date. If you are the interviewee and would like to update your choice of books (or even just what you say about them) please email us at [email protected]