Before we get to the books you’ve recommended, for someone who doesn’t know much about World War II, which would you say are the most critical battles to learn or read about? Where do I start?

There’s a little bit of a danger in reducing World War Two to a series of battles, in that it’s an enormously complex, massive subject. If you were looking at it from the point of view of being occupied, being Jewish, being a housewife working 18-hour shifts to produce B-17 bombers, if you were a kid in the East End of London during the Blitz—I think those are dimensions of the war which are, to me, equally fascinating. It’s like looking at any society or any issue and saying, ‘You can reduce it to these major events.’ There are so many things around them that need to be understood.

But I think that you can definitely say that there were critical battles. In terms of the defeat of Nazism in Europe, you’d have to pick Stalingrad. That would be the first turning point, really. If you look at World War Two, that’s when Hitler’s ambitions in the East were dealt a very serious blow. From that point on, the Germans were pretty much in retreat. There are a few notable counterattacks, but it’s a steady demise from January of 1943 onwards.

Certainly, news of the defeat at Stalingrad gave people throughout the resistance movement in Europe enormous hope. It was the first signal that this nightmare might one day end and that the Third Reich might be defeated.

People who don’t know much about World War Two tend to know that it was an immensely bloody, brutal affair—well north of 50 million people died, most of them civilians. But many forget that in Europe it was the Eastern Front where most of the bloodletting was done. Around three-quarters of the Wehrmacht, which is the German army, died on the Eastern Front. There were enormous losses by the Red Army. Historians debate the exact number—it’s impossible to find—but it’s probably around 10-12 million. Then you have millions and millions and millions more civilians.

Stalingrad has an enormous emotional significance today for Russians. If you look at the way Russians view the Second World War, they still call it the Great Patriotic War or Patriotic War. They rightly feel that their contribution to World War Two has never been adequately celebrated or recognized in the West. They did the bleeding. We did the industrial hard work and there was a lot of hard fighting in Western Europe. Western Europe would not be democratic today had we not been involved. But the real sacrifice in terms of human life was done by the people of the Soviet Union.

“Around three-quarters of the Wehrmacht…died on the Eastern Front”

As a Brit, I have to say that the Battle of Britain was also critical. If we hadn’t prevailed during the summer and fall of 1940, there wouldn’t have been a launching pad for the liberation of Europe. There wouldn’t have been a D-Day on June 6, 1944. We were very fortunate to have 23 miles of English Channel, separating us from France. Had that not existed, we would, I think, inevitably have been crushed too. The scale of the defeat of the French and us in the spring and early summer of 1940 is hard to overestimate. Blitzkrieg—the German way of war, the coordination between airstrikes and ground forces, Panzer units in particular—was devastating. No one could resist it. The Poles found out first. We and the French found out in the Battle of France, in 1940, what we were up against. Then there was the miracle of Dunkirk, where we managed to get over 300,000 British troops out of France. That left us with the rump of an army, but all our equipment and materiel was left behind.

So the Battle of Britain was vital. One of the really romantic things about the Battle of Britain is that Churchill famously said, “Never in the field of human conflict was so much owed by so many to so few” and it’s true. You’d have to look hard in all of military history for a battle where so few people made such a critical difference. It was around about 3,000 Allied pilots. The majority were British, but there were Canadians, Poles, New Zealanders, Australians, even a Jamaican among the pilots.

That’s not a lot of people to save Western civilization and I believe that’s exactly what they did. Hitler set a precondition that he was not going to launch Operation Sea Lion—which was the invasion of Britain—until he had control of the airspace across the English Channel in southern England. The Battle of Britain was fought with that as the aim, at least for the Germans. And because they never achieved it—and in fact, the rate of attrition in terms of aircraft climbed in the fall of 1940—Operation Sea Lion was postponed. Then, by the time you got into 1941, you had Operation Barbarossa, which was the invasion of the Soviet Union, and the invasion of Britain was forgotten. It was not something that the Germans wanted to take on: they were too occupied elsewhere.

Towards late August of 1940, we were in desperate straits. There was a shortage of leaders in the air, of experienced people who could actually lead young Brits into combat. We had enough planes but we didn’t have enough people to fly them and we couldn’t train them quickly enough. We were losing squadron leaders and experienced pilots because the frequency of being scrambled, of being in dogfights, meant life expectancy wasn’t that long. By August 1940, an RAF pilot could expect to live maybe three weeks.

Also, the Germans had targeted our airfields, our radar bases and our infrastructure and done a very good job of causing a lot of damage. Churchill was extremely worried. The 17th of August was called the hardest day. That was the day when the RAF was really pushed to the very edge.

But as so often during World War Two, the Germans made a key strategic mistake. They started to shift their focus away from airfields and defensive infrastructure and towards civilian targets. That’s why you end up with the first day of the Blitz, when the Germans attacked London, on the seventh of September, 1940. They decided to terrorize British cities rather than continue the excellent job they were doing of destroying the RAF on the ground. It was not great news for Londoners, but it was the breathing space that the RAF needed to rearm, to reequip, to repair runways, to train and put more pilots into planes. So we got away with it, but it was by the skin of our teeth. I don’t think people realize just how close we came to defeat in the Battle of Britain.

Some people say that there was no such thing as a ‘victory’ in the Battle of Britain. We just slugged each other to the point where we were both on the ropes. But I think it was a clear victory because the Germans didn’t launch Operation Sea Lion. If they had, we had nothing, really, to fight with because we’d left it all behind in France.

If you’re British, you can’t really over-romanticize what the Battle of Britain symbolized and I don’t think we can ever be appreciative enough of what those young pilots gave: many of them their lives. It was a grueling, but unbelievably important ultimate victory that changed the entire outcome of the Second World War.

“The real sacrifice in terms of human life was done by the people of the Soviet Union”

In the Pacific, an important battle is Midway, in early 1942. It wasn’t realized quite at the time, but that was a big turning point that blunted the advance of the Japanese Navy in the Pacific. Just a couple of dozen pilots, many of whom were killed, attacked Japanese aircraft carriers and sank four. The Imperial Japanese fleet lost its aircraft capacity in a significant way, and therefore could not continue its expansion in the Pacific. The invasion of Hawaii was impossible.

Then, clearly, the Battle of Normandy in June, July and August of 1944 was hugely significant in terms of liberating France and joining the war in northwestern Europe. The Allies had already been fighting in North Africa since 1940. The Americans arrived in November 1942, and there were campaigns all through North Africa, and then Sicily and Italy in 1943 and 44.

But in terms of one significant day in Western Europe, you’d have to say that it was the sixth of June 1944. The success of that was fundamental to the liberation of Western Europe, and the defeat of Nazi Germany. If we had failed—and we came close—there was no plan B. None of the senior commanders of Overlord were really confident of success. In fact, the higher up you went, the more worried they were. Churchill himself was terribly concerned that it might end up in a bloody disaster. We wouldn’t have been able to launch another operation like Overlord again in 1944. Bradley, the US general, said we wouldn’t have been able to ever go again. That would have been it. Eisenhower said they were putting all their money on one roll of the dice. It was a huge gamble. So D-Day, 1944, would be another battle that was critical.

So those would be the big turning points, whereby had the Allies not prevailed, what would have happened?

Let’s move to the books you’re recommending. What were your criteria in choosing these five?

They’re just my favorites. If this was a Desert Island Discs of World War Two, they would be at the top of my list. They’re really gripping reads and over the years, they’re ones that I come back to and enjoy again and again. I think they explain a lot about the perpetual fascination that people have with World War Two. If you want to be captivated by great storytelling and immersed in the drama, the heroism and the tragedy of World War Two, then these are the books that would lead to deeper reading. None of them are very long. Stalingrad, I think, is the longest.

Let’s start with that one. You’ve already mentioned the battle for Stalingrad (August 1942-February 1943) as a turning point of the war. Why is Antony Beevor’s such a good book to read about it?

He’s written a lot of good books and he’s rightly considered to be a preeminent historian of World War Two. For me, Stalingrad is by far his best book, and I’ve read nearly all of them. It’s magnificent and gripping. He took a story that hadn’t been told for quite a while and did a lot of important new research. There was that window when you could actually get into the archives, and he was able to get in. He just told a damn good story. It’s a wonderful story anyway, but he told it in a way that—it’s a cliché—was hard to put down. It’s very easy to put down history books, especially big, long tomes. They’re not usually written for the benefit of the casual reader or to be page-turners. This was just really good storytelling. He followed the rhythms of a great narrative, the way the battle developed, the climax, the way that everything became very brutal and very tense. He did a superb job of tracking that narrative and making it really come to life.

Yes, it draws you in right from the opening pages, as he takes you around all the Soviets, including Stalin, who are sure Hitler isn’t going to invade. They think he’s just playing a trick on the Allies and are completely wrong-footed when he launches Barbarossa.

It’s a really fantastic read. Antony Beevor did an awesome job. In terms of taking a big battle and making it really gripping and accessible, I’d say it’s the best World War Two book that I’ve read. It’s a classic.

Okay, let’s move on to a book about D-Day (June 6th, 1944), which is Cornelius Ryan’s The Longest Day, published in 1959. After all these years, is it still the best book on D-Day?

Yes. Cornelius Ryan was a war correspondent who had the benefit of witnessing the battle at the time and then interviewing key people. It was pretty useful to be writing then, because the main players were still alive. He could interview division commanders and the people who made really significant decisions, as well as a lot of guys who were there.

A lot of people know about The Longest Day because it became a very expensive (and long) movie but it’s actually a pretty short book. You can read it in the time it takes you to get across the English Channel on the ferry. So if anybody is going to the Normandy beaches, they can just take The Longest Day. It’s the ultimate primer on D-Day and you can read it while sipping a beer or cup of tea in the bar on the cross-channel ferry.

Cornelius Ryan interviewed hundreds of people for the book. It’s almost history as pointillism. He had access to an enormous amount of information. He sent out questionnaires. If you look at the Ryan archive, it shows you all the material that he gathered for The Longest Day, and it’s really impressive.

But he had the discipline, as a really experienced and concise journalist, to say, ‘Okay, I could write a 600- or 700-page book, but I’m not going to.’ It’s short and precise. It’s condensed everything down to the essence of what was dramatic but also important. The story is really well told.

Historians would argue, after further review and much more research, that there may be some mistakes or a misinterpretation here or there. There are many areas where you could argue that things were perhaps different or could be interpreted differently. But as an introduction to D-Day that gives you the overall picture, that captures the drama and the enormity of it, and the heroism, and covers the German side as well as the Allied side, there’s nothing better. And I don’t think there ever will be.

So were you a bit nervous when you started writing your book about D-Day? What was your approach?

You try and take a different angle. If you can find people who are still alive that haven’t spoken before or, in archive material, if you can find new stuff that hasn’t been used before, that’s what you’re aiming for. With The Bedford Boys, it was told from the point of view of a small unit—a company of less than 200 men—who fought on D-Day, but it was also told from the point of view of the families and loved ones of those men back in the US. In the book, I cut between Britain, Normandy, and Bedford, a small community in the heart of Virginia. It’ll be a chapter with the guys in Europe getting the training and ready to go and then I come back to the US. I develop the story pretty well in parts of it, so that you understand the cost to one community of that sacrifice on D-Day.

So if you’re an American and you were to go and visit Normandy, The Bedford Boys is a recommendation that a lot of people would give you, as a book to read to understand D-Day on a very personal level. It’s not the massive broad picture that Cornelius Ryan presents very well. Although I tell the overall story of the day, I do it very much from the point of view of this unit of men from Bedford, Virginia.

There were 34 of them on D-Day, and 19 of them were killed in the first hour or so of the invasion. That’s why Bedford, Virginia is the place where they have the National D-Day Memorial in the US, because it’s been estimated it’s the community that, per capita, had the highest loss of any Allied community on D-Day.

So that book was quite a new approach. I don’t think anybody had ever told the story of a battle from the point of view of the wives, the kids and the parents back home. If I don’t do anything else in my life, it will be one thing that I will look back on and think, ‘Well, that was interesting.’

Is it your favourite of your own books?

I don’t know whether any books are a favourite but I think it meant something to quite a few people in Bedford, Virginia, and it told the D-Day story in a new way. Therefore, hopefully, a couple of people will read it long after I’m gone. I’m not being falsely modest. It did feel like new ground was being broken.

I also did another book about D-Day called The First Wave which was just an unashamed ‘Greatest Hits’ approach. I just picked my favorite guys from the Canadians, the Brits, the Americans and even a Frenchman. I decided, ‘I’m just going to tell this incredible story but tell it up close and personal from the point of view of my eight stars and really go to town.’ There wasn’t a lot that was enormously new but the angle there was somewhat innovative in that I took the combat leaders who were in action first, who had the most critical missions. They landed first—either from the air or the sea—and if they didn’t succeed in the first minutes or hours of D-Day, then the whole operation would have failed. So it was an interesting approach and I got to hero worship some really cool guys. There’s nothing wrong with hero worship when it comes to people who were prepared to die to save everything that we care about.

Let’s go on to the Battle of Britain (Jul-Oct 1940). The next book you’ve chosen is Reach for the Sky by Paul Brickhill. Tell me why this is on your list of favourites.

If you could have only one author of World War Two books on your desert island, I would say take Paul Brickhill with you. He was an Australian fighter pilot who had been through World War II and just had a nose for a fantastic story. It was almost as if he said to himself, ‘What would make a Hollywood blockbuster? I’m going to write the true story.’ He also wrote The Great Escape—which became a really good movie with Steve McQueen—and The Dambusters. Reach for the Sky was also turned into a movie. So he had a really great strike rate. The books, again, are really short. I think they’re even shorter than The Longest Day. (You’ll note that brevity is a common theme).

Reach for the Sky is about Douglas Bader, the legless Second World War flying ace and an extraordinary character. He lost both his legs in a flying accident in the 1930s and somehow—through bluster and bravado and connections and just doggedness—persuaded the RAF to allow him to return to combat and he flew in the Battle of Britain. He was a very good pilot, obviously. The stirrups in the Spitfire were changed for his false legs. It’s a massive inspiration to anybody that’s lost their legs because here’s a guy who thought his world had ended and went on to fly in dogfights in the Battle of Britain.

“They’re really gripping reads and over the years, they’re ones that I come back to and enjoy again and again”

Then, he was shot down and taken prisoner. He was a legend among the Germans and while he was recuperating in a hospital in Normandy, he was asked ‘Can we do anything for you?’ I believe it was Adolf Galland—one of the leading German fighter pilots—who was involved in that decision. There was a certain gentlemanly conduct between the Luftwaffe and the RAF. It’s been overly romanticized but it wasn’t like on the Eastern Front, where they killed each other whenever they possibly could.

Bader replied that he needed new legs and the Germans arranged for the RAF to drop in the legs and they were delivered to Bader. It’s an extraordinary story.

The first thing Bader did once he had fitted the legs was to try and escape. He continued to try to escape throughout the rest of the war and was placed in Colditz. Colditz was the maximum-security prison that the Germans had for serial escapers—people who thought it was their duty to try and escape and kept on doing it—along with some high-profile prisoners. Ben Macintyre wrote a really good account of Colditz just last year. That, again, is a wonderful story. Bader escaped from Colditz. Here’s a guy that couldn’t be put down, he was just indomitable.

The book starts with Bader’s childhood, does it cover his whole life?

It goes through to the end of the war, basically.

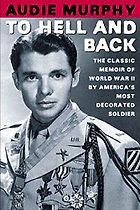

Let’s go on to your next book, To Hell and Back, which is the memoir of an American soldier, Audie Murphy, who fought across Europe. It’s good to have a book that covers the US experience on this list, given how critical they were.

From the day that Churchill came into power in May of 1940, he really only had one objective. A lot of Brits don’t like to hear this, but he knew that there was no chance for Britain, or the Empire, unless they “dragged” the United States into the war, as he put it. Almost daily until Pearl Harbor in December 1941, Churchill was doing everything he possibly could to get the United States into the war. He was relieved when Pearl Harbor happened because then, finally, the Americans were a part of the worldwide effort.

But I should stress that Germany declared war on the United States, not the other way around. It was Hitler who decided—because of the Tripartite agreement between the Italians, the Japanese and the Germans—to declare war on the United States. So you might want to ask yourself, what would have happened if Hitler hadn’t done that? Would the US—seriously under-armed and taken by surprise—have engaged in the Pacific against the Japanese and then gone to war in Europe? You could make a good argument for saying they might not have. Their war was with the Japanese, not Nazi Germany. Thankfully, Hitler made that massive geopolitical error and the industrial might of the United States helped us massively.

Tell me about Audie Murphy, who started off the war with the US Army in Morocco, I believe.

The 3rd Infantry Division (ID) that he belonged to began in North Africa in November 1942, but Audie Murphy didn’t see any combat until the 10th of July, 1943, in Sicily. He was in B company of the 15th Infantry Regiment. Among the American divisions, the 3rd ID fought the longest in the European theater. They went all the way from North Africa to Berchtesgaden in Germany, which is an awful long way. They had the most Medal of Honor recipients of any American division in Europe, Audie Murphy being one of them. He was the most decorated US infantryman of World War Two, gaining every medal that you could possibly get for valour.

He was a really skinny, small guy who had been rejected by the Marines and the Navy. He was allowed into the US Army on his second attempt, I believe. He was the last guy you’d think would end up being this incredible warrior, unrivaled in terms of medals, in World War Two.

He wrote this book, To Hell and Back, which was also turned into a movie. It’s very intense, a great distraction. I think most of it is true. There is a little bit of dramatization here and there, and a bit of dialogue that I’m not sure would really have happened. But when I was writing about Audie Murphy, I read the book several times and I looked at the archival material as well. Surprisingly, a lot of it was spot on. I was quite taken by the fact that what he wrote corresponded to what had actually happened because it’s quite difficult to do. He was a lowly private at the beginning of the war and you really have no idea what’s going on in terms of the big picture. Your recollections are very fragmentary. Also, because of trauma, the violence, the loss and the chaos, it’s hard to create a narrative that actually intersects with what happened. It’s only afterwards that you can put it in context. So he did a good job.

Five Books interviews are expensive to produce. If you're enjoying this interview, please support us by donating a small amount.

It’s a really fun read, very enjoyable. His story is also remarkable. When they made the movie, he actually played himself. It was a really big hit at the time, I think the highest-grossing movie for Paramount up until that point. It made him wealthy. Much of that wealth he gambled away later on in his life. It still is a good movie. A lot of people might sit there and go, ‘It’s so corny!’ but I actually think it’s really fun and watchable.

You’d be very hard-pressed to find someone who saw as much combat in the critical battles in the liberation of Western Europe, and experienced as much of the grit and the grime and the horror of war, as Audie Murphy. He had an extraordinary ability to lead. He’s about as close as you can come to an effective predator, in a uniform, in the US Army, in World War Two. He was extraordinarily good at killing people and very good at not getting killed. And whether people want to embrace this fully or not, you needed people like that to get the job done. In many battles, when it really came down to it, you needed people to get out of foxholes and attack and destroy the enemy. In terms of Western Europe, whether it was the Brits, the Canadians, or the Yanks, it didn’t matter: We were aiming for Berlin and Berlin is a long way away from Casablanca. It’s a long way from Normandy, even.

You had to get up most days and attack. The Germans, often, were defending. It takes a certain kind of person to do that over and over and over again. And to do it willingly. The vast majority of people in that situation are terrified. They’re scared and they’re not going to put their life on the line. They’ll do what they’re told, they’ll do things automatically if they’re trained, but to be enterprising, to actually consciously put your life on the line over and over and over again and to do something that goes beyond the call of duty is rare. And I think Audie Murphy was probably the rarest of the rare.

So was he fighting in Sicily and then up at Monte Cassino? What was the route?

He went all the way across Sicily. Then there was the Salerno invasion in September 1943. He fought with the 3rd ID all the way up the spine of central Italy. He was at Anzio, in January 1944. He was wounded there, then came back in at the end of the battle and was part of the breakout. His fourth amphibious invasion was Operation Dragoon, in August of 1944. This summer, I was actually at the vineyard where he earned his DSC or Distinguished Service Cross. You can see the beach at St Tropez where they came ashore.

Then he fought all the way up the Rhone Valley, through the Vosges mountains, was in the Battle of the Colmar Pocket in January and February of 1945. That’s close to the German border and where he earned the Medal of Honor. Finally, he was taken off the frontline in March of 1945 because you didn’t want your Medal of Honor recipients to be killed in action: they were too useful as propaganda figures. Although I would argue that with someone like Murphy, you should have just kept him in the line because he was so effective. Other people can raise war bonds.

So he’d gone all the way from Sicily to Salzburg—where he received the Medal of Honor in June of 1945, after the war had ended—and was still only 20 years old. He had killed a lot—some people say he killed over 250 Germans, which is a ridiculous statement. He was totally brutalized and had massive PTSD.

His face appeared on the front cover of Life magazine in July of 1945. He was handsome and the literal cover boy for American heroism in World War Two. Jimmy Cagney, the actor who played gangsters in Hollywood, saw him on the cover of Life and said, ‘Wow, who’s this kid? He could be a movie star! He’s the real deal, the action hero.’ Cagney contacted Audie Murphy and flew him out to Hollywood in the fall of 1945. He let him sleep in his pool house, paid for acting lessons, put him into a gym, fattened him up.

And then, lo and behold, Audie Murphy ended up being a big star and appearing in more than 30 movies. To Hell and Back was a blockbuster movie in 1955. As I said, Audie Murphy played himself, including the scene where his best friend was killed and other key moments. He was still hugely traumatized with a serious case of PTSD as he reenacted those scenes. He actually asked the producers to cut the scene where he received the Medal of Honor but they thought it was the climax and too important not to have in the movie. So they finally persuaded him to keep it in, but it tells you a little bit about his mindset.

In your book, Against All Odds, do you follow Audie Murphy and three other Medal of Honor winners from the same division?

Yes, and I follow them not just to the end of the war, but afterwards. The last quarter of the book is post-World War Two. Audie Murphy had a very interesting second chapter of his life, being a movie star. He wrote a lot of country and western songs and starred in a lot of westerns.

But he was deeply scarred by the war. He slept with a pistol under his pillow and had troubled relationships. The remarkable thing is that, given how much he’d seen and how much he endured, he was even able to function at all, that he didn’t just go and drink himself to death or commit suicide. One thing that a lot of the characters in these books I’m talking about have in common is incredible resilience. He certainly had it.

We’d better get on to your last book, which is about World War II, but more about emotional battles than military ones. I’m glad you’ve included it, though. This is French novelist Marguerite Duras’s memoir of living in occupied Paris.

This is one of the most deeply moving books I’ve ever read. There’s one part of it which is about her partner at the time, Robert Antelme. He was part of the French Resistance and was imprisoned in Dachau concentration camp. When I was researching The Liberator—which is a book that came out in 2012 about a guy who ended up liberating Dachau—I was looking for suitable characters that I could have in Dachau, as the liberating forces were approaching. I did a lot of research and found Robert Antelme, who was a really cool guy.

Then I came across Margaret Duras’s book, which tells the story of her relationship with him. It’s so powerful. Duras’s description of how she nursed him when he arrived back in Paris…it’s difficult to turn the pages. She talks about having to feed him so delicately with a spoon, with a very thin broth, how you could see through his skin to his ribs and his internal organs. That’s how emaciated he was. He was actually rescued from Dachau by Francois Mitterand, the future French president. She writes about how, when he was driven back from Germany to Paris by Mitterand, Mitterand was afraid that if they went across too many bumps in the road that it would literally kill him. He was so close death. Duras writes about how she was terrified of the responsibility that she now confronted of having to try and save him, to try and nurse him back to some kind of health.

The kicker is that she no longer loved him. She had had relationships and fallen in love with somebody else. But she did everything that she was capable of doing to give Antelme the chance of living. Then there’s a scene near the end where she has to tell him, ‘You’ve recovered sufficiently to walk on your own, but we can’t be together.’ It’s enormously powerful.

I just remember the descriptions of how she fed him, what would go in at one end of his body and come out at the other. It’s extraordinary. It’s an incredible account of what you can do for someone. He was a great writer too. He only wrote one book, about his experience in Dachau.

Does the book cover the whole war, if you’re interested in the occupation of Paris?

It’s not the whole war. There are a number of novellas within the book that cover different aspects of the war. One, controversially, involves her relationship with a German. But the relationship with Antelm is the one that forms most of the book, and it’s really, really well done. It’s really moving. I was always taken with the idea that you can devote almost every last ounce of your energy to somebody else and then break their heart. It’s the kind of thing that Duras, as a writer, excelled at, this sort of ambivalence and complexity and things that people might not like to dwell on too much.

When people think of Margaret Duras, they don’t think of this memoir, but for me, it’s her most powerful, beautiful writing. It’s very elegant and moving. As a woman writing about her experiences in World War Two, about what Nazism did to people and the consequences of trying to bring someone to life after that evil, there’s nothing like it. It’s really extraordinary.

So with your own books, I get the sense you’re more interested in the individuals and their stories: the battles are more of a backdrop?

I’m not that interested in strategy or tactics, or what the inside of a tank looks like. I’m finishing a book now about the Battle of the Bulge and my editor has a whole bunch of notes like, ‘More on weapons, people love tanks’ or ‘Where were they on this day? Where are they moving towards?’ These are good points, and you have to address them. But I’m much more interested in what they were feeling and thinking and how they coped with the stress, what they believed in, what motivated them, how much they loved the guys around them, how they led their lives later, how they endured, what they were inspired by, whether they prayed, whether they didn’t pray.

The thing about World War Two that is really compelling for me—and always will be—is that it’s like the perfect pressure cooker for testing humanity in different ways. With Duras, it’s ‘How do you save someone you don’t want to be with?’ With Audie Murphy it’s ‘How do you carry on? How do you keep moving? How do you wake up every day and do the impossible? And then how, when you emerge from that, do you put the thing that disfigures and scars you to the side and still function?’ Those are the things that are enduring about World War II. It’s not about lots of people killing each other and flag waving and ‘aren’t we wonderful?’ and all that. It’s about human beings tested over and over again.

And I suppose, as a reader, you’re wondering what you would have done if it had been you. I saw that in a comment on the Marguerite Duras memoir: ‘It really makes you think: What would I have done in that position?’

Yes. It’s a good question.

Interview by Sophie Roell, Editor

September 7, 2023. Updated: September 12, 2023

Five Books aims to keep its book recommendations and interviews up to date. If you are the interviewee and would like to update your choice of books (or even just what you say about them) please email us at [email protected]