To start with, tell me a bit about this prize, set up in 1956 in honour of the British diplomat and author Duff Cooper, I believe. It’s looking for the best nonfiction books of the year, is that right?

It’s a very long-established prize and has had an extraordinary list of winners over the years. We wanted our winners to last, and they have done. That’s what we have in mind.

We’re looking for nonfiction books. I suppose that they would count as very literary nonfiction books. I don’t particularly speak for the other judges, but if they were clunkily written or not very beautifully written, they wouldn’t feature on our list because we’re looking for books that are distinguished, are beautiful, are going to last, are original, and which make a real contribution. I think that the past winners show that.

Duff Cooper himself was rather a legendary figure. He was the ambassador in France and very glamorous. This prize is aided and sponsored by Pol Roger, the champagne makers, which is rather fitting.

In terms of the nonfiction books you’re looking for, is it tilted towards history and biography and the things Duff Cooper himself was interested in?

It seems to be. A self-help book on diet wouldn’t cut it for the judges. They’re often history, biography, and art history. Political memoir might feature too, I suppose, but it wouldn’t often get to the prize spot.

Why do you think that is?

The judges call in the books, so it’s very much a matter of the personal choice of the particular judges, but somehow it comes together that the winner is this sort of starry literary book. These books are meant to be for general readers, but they seem to have a different complexion from the shortlist of say, the Baillie Gifford Prize for Non-Fiction (once the Samuel Johnson Prize), which often rewards topicality, or the Wolfson History Prize, which tends towards academic big-hitters.

One other thing I wanted to mention is that I don’t know any of these authors personally.

Let’s start with The Revolutionary Temper, by Robert Darnton, a historian of 18th-century France. Can you tell me what it’s about and why you liked it?

This is an enthralling account of life on the streets of pre-revolutionary Paris. It’s full of wonders and surprises, even though you would think that this is rather a well-ploughed field. It’s so wonderfully vivid. Darnton, who is the master of Paris and of the surprising angle on what was going on, looks back to the fifty years of the ancien régime before the French Revolution.

He tracks back to see how one of the great revolutions of history, in 1789, could possibly have happened, how the unthinkable happened, and how the will of the people can overthrow the power of kings. It takes you to people who are suffering from hunger and penury and oppressed by the nobles, but it’s really looking at ideas, and how ideas circulate. The medium is the message, so it’s looking at the ‘nouvelles’— the newssheets and newspapers and pamphlets and rumour.

“We’re looking for books that are distinguished, are beautiful, are going to last”

I know this period a bit, but I was very surprised because one moment, you’re looking at the Jansenists at Port Royal and the Jesuits; the next it’s the case of the diamond necklace, which is when Marie Antoinette is suspected of having strange relations with a cardinal in order to gain a great bauble. It takes you to mesmerism and the new hot air balloons, to people suddenly knowing about the royal debt and how the royal adultery can taint the power of kingship.

It’s a very sweeping account, but it’s very particular as well. There are all these short chapters, and you turn every page, not knowing what’s going to happen next, except it’s all building to this astonishing denouement. It’s an extraordinary book.

It opens with the battles at the end of the war of Austrian succession—how news of what happened came back to Paris and what people were saying about it. It’s fascinating to get that kind of insight into what people were thinking.

Yes. It’s always coming at you from left field, somehow. It’s full of songs. It’s a very original book, and the result of a lifetime of immersion in these events. It’s written by someone who’s in love with the period and wants to explain it. It’s wonderful.

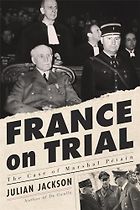

The next book on the shortlist is France on Trial by historian Julian Jackson, who focuses on the 20th century. Again, we’re back in France.

Yes. It’s by accident, but it’s turned into a French shortlist! We never know until we get to the shortlisting meeting what’s going to prevail. It is true that it’s Pol Roger and that the chair of the judges is a great French expert, but it’s a surprise.

This is an extraordinary book, again by a master—there are some very powerful historians on this shortlist. It’s bringing to life this very dark moment in recent French history: the trial of Marshal Pétain at the end of the Second World War. At that point, Pétain was nearly ninety.

Pétain had been the hero of Verdun, a great figure, but he was being tried for treason for signing the armistice with the Nazi regime and being the leader of the Vichy regime in France. He was on trial for his life, accused of collusion with Nazi Germany, and the verdict wasn’t much in doubt.

It’s about more than the fate of a particular person—it’s a judgment on these four years of French history. It was newly liberated France’s first opportunity to look back on what it had done and how it had come to this. It’s a terrible account of moral ambivalence, and what you should do when faced with a conquering army. France is asking itself what it could have done, faced with total defeat by Hitler.

The book takes you to the trial itself, and a cast of pretty repellent characters. Although the book is written with wit, there aren’t any jokes in it. If Pétain is guilty, then so are the French. We see that this still has consequences for modern-day French politics. These horrors haven’t really gone away in French history.

The two principal characters are Pétain himself and de Gaulle, but also the trial judges, the jury. The book is asking profound, historical questions about how to act in impossible circumstances, written by a very distinguished historian of France.

I hadn’t appreciated the extent of Pétain’s ups and downs—how he died imprisoned on an island off the coast of France.

Yes. The death penalty was taken away from him. It makes you think, too, about Napoleon and Saint Helena. Pétain is not exactly a scapegoat, but he’s a figurehead for this very right-wing, authoritarian, nationalist (in a pejorative sense), racist regime standing against those who we would see as the heroes of the Resistance. It’s the collaborators against the others, and this is a story that doesn’t go away.

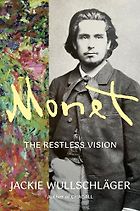

Next up, we’ve got a biography of the painter Claude Monet by Jackie Wullschläger. Tell me about this one.

This is a beautiful book. It’s full of light. Wullschläger writes so beautifully about the paintings, but also, she’s got such emotional intelligence. She’s got this vast panoply of Monet’s correspondence: thousands and thousands of letters. With the knowledge of the art, the person, and the other characters, she creates for us what she calls this ‘restless vision’, and that’s what it is. She’s trying to reconstruct Monet’s inner life, to tell Monet’s life and how he felt it.

As I read it, at first Monet is not an attractive character. You think, ‘This is absolutely why, as a woman, you should not live with an artist.’ It’s full of scrounging letters, and the suffering of these women who are, of course, immortalised in beautiful portraits by him, but following him around or being abandoned by him. You think, ‘Well, it’s the art, of course,’ but she explains quite how it is that he comes to revolutionise art and to create these ravishing works that are just luminous. She writes very beautifully about it.

Five Books interviews are expensive to produce. If you're enjoying this interview, please support us by donating a small amount.

As life goes on, instead of being improvident, he becomes very wealthy. Finally, you see him at Giverny employing six gardeners, one of whom has to dust off the water lilies! There’s great pathos. You’re won over to him, as his life goes on, and see how he, too, has suffered for his art.

It’s a rich and moving account. I’ve read quite a lot of art history, and it can be pretty rebarbative, but these are exquisite accounts of the paintings. She persuades you—if you needed persuading—just how important a figure he is.

It’s quite striking. It opens with his wife on her deathbed, and someone else coming to fill her shoes immediately. From the start, you’re involved in some sort of emotional journey.

It’s an account of these friendships. You see the moral compromises that he makes for his art, and all the scrounging and the rest that goes on. He suffers for it, and so do those around him.

Let’s move on to Christopher Clark’s book, Revolutionary Spring, which looks at the upheavals of 1848.

This is simply magnificent. Here is a great historian at the height of his powers—the control to tell this extraordinary story across such an epic range. This is history on the grand scale. It’s full of important historical truths—very deep and profound ones—and, also, particular accounts of particular people and particular places.

It’s very vivid. He’s looking at the great revolutions of 1848, from Budapest and Vienna and Galicia and Moldavia to France and Milan and Sicily. The number of languages and the range of understanding is extraordinary. He takes you to the particular sufferings of the peasantry and the townspeople—but finds that economic suffering may be partly a cause, but it’s not a sufficient cause of these revolutions.

He’s looking to politics and political ideas. He describes the precarious state in which people were living and shows how the revolutions ricochet, as one country and one city rises. The revolutions in different countries are quickly succeeded by each other but they don’t necessarily spark each other off.

It’s been a mystery how the revolutions happened, but he shows how they happen and, also, the consequences. They bring new freedoms, new constitutions, new parliaments, but in the end, the old order re-establishes itself. He describes a counter-revolutionary international. It’s an extraordinary achievement: a brilliant series of set pieces, but also this larger narrative.

Is it very readable? It’s obviously very long because it’s covering such broad ground, but is it something you could happily take to bed and read in the evenings?

It’s pretty hefty. You wouldn’t want to fall asleep with the book on your nose—you would be knocked out. I read on, agog. It’s just full of wonders and surprises and particular people with whom you feel sympathy and the bravery of the participants in all this.

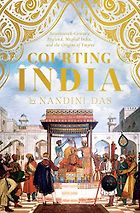

We’re now moving out of Europe. The last book on this year’s shortlist is Courting India by Nandini Das, a professor at Oxford. Tell me about this book and what you liked about it.

This book is vivid, it’s brilliant, it’s elegant. It’s full of surprises. It’s full of wonders. British historians know about the 1615 embassy of Sir Thomas Rowe from the court of James I of England to the great Mughal Empire of Jahangir. Das is a literary scholar, so she’s parsing these accounts. This is a book very long in gestation, I think. She also knows many other languages, and she’s steeped in the records of the East India Company, so she’s showing much more of the encounter.

This is little old fusty England encountering this extraordinary empire. Jahangir has got millions of men in his army. He’s ruling this glittering empire that goes from Afghanistan, through India to present-day Bangladesh and Pakistan. In fact, the embassy is a bit of a failure. What has England got to offer Jahangir?

The hapless ambassador to the second-order monarch finds himself in these extraordinary palaces, where he hangs around and it’s not even clear that he’s going to be given an audience. Das is conjuring this world. Every sentence gives you a present. It’s absolutely wonderful. It’s constructed like a Swiss watch: everything locks in and returns. One moment you find yourself in Jacobean London, and then, the next moment, you’re encountering something oriental and remote.

Going into the book, did you know much about the Mughal Empire?

I’m a great lover of India and Indian miniatures, and I have been to some of the Mughal palaces, but you could never get to the bottom of it. I simply adored it. I have had a go at writing diplomatic history myself, and it’s very difficult to do without the ‘he said, she said’ of it. Das just makes you realise what it is to be an ambassador, far from home, with all your hopes crumbling in both places.

Find out more about the Pol Roger Duff Cooper Prize. The winner will be announced on March 4th, 2024

Interview by Sophie Roell, Editor

February 22, 2024. Updated: March 4, 2025

Five Books aims to keep its book recommendations and interviews up to date. If you are the interviewee and would like to update your choice of books (or even just what you say about them) please email us at [email protected]