It seems like 2018 has been a good year for fiction. As chair of this year’s Booker Prize, how many books did you read to determine the longlist and then the shortlist?

I don’t normally read a couple of hundred novels in a single year, but it was a great pleasure reading them. We discussed about 171 or 172 books as a committee. To feed into the list, some of us read additional books to decide whether to recommend them to the whole group. Some we didn’t recommend, and so we didn’t all read them.

Was it clear what the longlist would be, or were there many great contenders?

We discussed 30 or so books at each meeting—30 books a month. We kept some and discarded others. When we came to the longlist meeting, we had to look at the ones we had still left, and get down to thirteen. Mostly what we did was talk; we produced a list that way.

I suppose I could have told you before the meeting some of the titles that would make the final cut, but I couldn’t have guessed the whole list. This is a very collaborative process. It’s not a matter of voting. It’s a matter of coming to a yes/no decision.

Critical consensus, even if you’re not unanimous.

Yes. We hardly ever voted. There was mostly agreement. After you discuss the book, you have a sense of where you all are. It was a very collaborative process, and the final result was a matter of listening to each other and respecting each other’s judgments.

Let’s first discuss the winning book, Milkman by Anna Burns. What is this book about, and why is it so special?

These novels aren’t exactly ‘about’ anything; that is to say, there are many subjects they’re about, not just one. Each evokes a world which prompts the reader to think about many things.

That said, I think this is clearly a novel in some sense about divided societies. It’s a novel about how in any divided society, men can abuse their positions to take advantage of women. I think it’s also a novel about the terrifying power of gossip, and the way in which the circulation of stories about people—true or false—can shape their own options.

“Milkman is a novel about the terrifying power of gossip”

Though it’s obvious that it grows out of Burns’ own society, Northern Ireland and the conflicts there, I felt very much that it was the sort of novel that would help you to think about any divided society. I suspect that people who lived in Lebanon or Syria or Sri Lanka would see echoes. It’s that mixture of the particular and the universal that is there in a lot of great writing.

It’s also the mixture of the contemporary and the timeless. Responding to an interviewer pointing out that the novel’s focus on stalking is resonant in the #MeToo age, Anna Burns responded that she wrote it before any of that.

Yes. Obviously, it’s about things that #MeToo is addressing. But it’s very writerly in the sense that it evokes a world without really banging you over the head with what you’re supposed to think about anything. The world itself—the world that she’s created—is the interesting thing.

The young woman at the heart of the novel is a surprising person in many ways. She reads a lot in a society that doesn’t seem very interested in literature. She’s learning French, for no obvious reason except that she wants to learn French. She has a young man she’s actually interested in, and then she’s chased by this other man who she’s not interested in. She’s quite smart: she realizes what she can and can’t do. She’s very conscious of the ways in which the circulation of gossip means that everything she does will be interpreted in a certain way—the wrong way, usually.

Much of the book’s press around the time of the Booker announcement talked about Milkman as a ‘difficult’ book. Why is this? When I read it, that label seemed like a misappellation.

When we announced the winner to the press at the dinner, a journalist said it was very challenging, and I said something about how it was challenging in the sort of way that a stroll up Snowdon is challenging. It’s challenging because it’s a little uphill, but it’s worth it for the view, you know. It wasn’t my choice to describe it as challenging—it was the journalist’s choice to ask me about that. I wouldn’t have used that term.

We read it three times. We read it to put it on the longlist; we read it between the longlist and the shortlist; and then we read it again. It’s a novel for the ear as well as for the mind—I found myself reading it out loud to myself sometimes. She’s talking to us, in a very plausible (though peculiar) voice. I imagine the audiobook is going to do well, purely because her voice is so compelling. If you have any difficulty figuring out what a sentence is about, all you have to do is read it out loud and it’s perfectly clear.

“You couldn’t mistake this novel for any other”

Just as all interesting writing is unlike anything else, you couldn’t mistake this novel for any other. It’s not very much like anything else I’ve read; it’s very particular. But once you get into it, it just goes along. Partly because you want to know what’s going to happen.

Obviously, I read it more than once, and interestingly I still found myself being pulled along. Even though I knew what was going to happen, I wanted to remember exactly how things happened.

Next, we have Washington Black by Esi Edugyan. Tell us about this novel.

This is a very distinctive piece of writing. The main character, Washington Black, begins his life enslaved in the Caribbean under a very cruel master and cruel regime. We modern people know slavery was bad, but we forget just quite how bad it was. It very much evokes that. It’s quite painful to read that part, I think.

He’s raised thinking he’s an orphan, but in fact—spoiler alert—it turns out the woman he’s looking after is actually his mother (though, for some reason, she doesn’t want him to know that.) She’s a very powerful character, because she was born in Africa and brings something of Africa with her.

The other main character is the younger brother of the plantation owner. He’s a quiet abolitionist who doesn’t really approve of slavery. He’s also one of those aristocratic European amateur scientists. Part of what he’s doing on the island visiting his brother is finding a place where he can test out a balloon that he’s made which is supposed to carry people off into the air. After a series of complicated events, he takes Washington with him to escape from the island.

Get the weekly Five Books newsletter

From now on, it’s partly a picaresque adventure story. They’re going from the Caribbean to North America to the Arctic to London, and he ends up in Morocco. It’s an adventure story; it’s also a love story. It’s also a story about that 19th-century period when this man Titch, the brother of the plantation owner, experiences conflicted feelings about the fact that they’ve developed a rather intimate relationship. He pulls out of it at a certain point, and then most of the remaining novel is about life in London as a free man with a woman he loves and who loves him, despite the fact that he’s badly mutilated as the result of an accident.

It’s written looking backwards. What you see is that the result of the education of this young man by an older Englishman is ultimately developing quite a sophisticated understanding of the world, one which he clearly didn’t have at the start. You might wonder how an illiterate slave could have an interesting point of view, and he starts out that way, but by the end he becomes a sophisticated person. He learns a lot of the science that Titch is doing. Titch also allows him to draw, and he discovers he has capacity as an artist.

It sounds like a novel with just extraordinary range.

Its range is astonishing. It’s an adventure story, so it’s beautifully written, but a lot of the time—and this is why it was good to read it more than once—you rush through because it’s so exciting. You’re in the Arctic, and somebody’s disappeared into the snow and you’re wondering whether they’re going to survive. Or they’re in the balloon, and you don’t know what’s going to happen. They’re being chased by someone who’s trying to recover him as a slave, who’s a slave-chaser—is he going to find him? What’s going to happen when they meet? There’s a lot of excitement.

It’s a rather odd test, the Booker. To survive it, you have to be read by some fairly attentive readers several times over. Though I’m sure most writers would love to be read more than once, most books are meant to be read by most readers once. Part of the interest of a book like this is that you discover new things each time you read it. There’s so much in there.

Washington Black has an enormous range: a geographical range, a range of emotions, a range of kinds of people. It has a Javert-like character trying to find him because there’s a huge bounty on his head. It’s fun.

It seems like all of the shortlisted books have to be able to succeed in both a sprint and a marathon.

Yes. You might think it’s an odd way to evaluate things, but I’m extremely fond of the books that got that far, in part because we got to know them quite well.

Let’s move on to Everything Under by Daisy Johnson. She was the youngest author on the shortlist, and the pre-announcement favourite, as I understand it. What’s so captivating about this novel?

Here, the writing is very distinctive, too. Most extraordinary is its evocation of a world that’s in a way contemporary, but pretty unfamiliar to most of us. It’s a world of people at the bottom of the socioeconomic hierarchy of British society (it’s set in England), living on canals, often eating fish they’ve caught themselves or rabbits they’ve hunted.

It’s also retelling of an Oedipus narrative. The main character is a trans person. If you think about the structure of the Oedipus story, you have to have someone who doesn’t know who their parents are causing the death of the father, and having sex with the mother. You might think that’s awfully difficult to pull off with a trans character, but somehow it works. It’s obviously recognisable at some points that you’re in an Oedipus story, but it somehow doesn’t feel at all that that’s an unnatural structure. It doesn’t feel like you’re being forced to go through the structure of an existing archetypical narrative. Many surprising things happen, but they don’t seem forced.

Five Books interviews are expensive to produce. If you're enjoying this interview, please support us by donating a small amount.

We’re living in a time when trans issues are front and centre in our social and political lives, but Everything Under is telling a story with an age-old structure—a structure of the child who doesn’t know who he or she is. The child who the Fates, as it were, have determined will do the very thing that everybody was trying to avoid. Johnson’s language, too, is beautiful. It evokes a world that’s extremely unfamiliar, but makes it feel like a natural world. It’s incredibly well done.

You said she was the youngest person on the list. When putting it together, we didn’t really think about anything except the book. We didn’t think about how old or young anybody was; we didn’t think about whether anybody had ever been on the shortlist before. We didn’t think about whether they were white or not. We just ended up with six favourites. Though it was a quite diverse list in respect to things like age, first novels versus people who’ve been at it a while, that wasn’t really the point. It’s a sign of the vigour of the novel in English. An incredible range of people are doing an incredible range of things. Some of it is done by people who’ve been at it a long time, and some of it is by people who are just starting.

Speaking of people who’ve been at it a long time, the next author on the shortlist is Rachel Kushner, with her novel The Mars Room. She’s had bestselling novels before. What makes this book stand out?

This is a novel set in a part of modern life unfamiliar to most of us: a women’s prison. Of course, most of the characters in a women’s prison are going to be women. There are a few men important to the plot, including the one that the main character, 29 year-old single mother Romy Hall, is in prison for killing.

Romy is an interesting character. She’s been a sex worker. She’s had problems (and pleasures) with drugs. She’s had abusive relations with men. But she’s quite thoughtful and intellectually sophisticated, though not in a way inconsistent with realism—with thinking that someone in her circumstances might actually think those thoughts. Sometimes, when a highly educated author writes about a character who, say, hasn’t been to college, the writer can put things in the character’s mouth that lead the reader to think, ‘Well, that’s you—that couldn’t be her.’ I didn’t ever feel that with this novel. She’s a well-made character who speaks in a plausible voice, who knows the sort of things that someone in her circumstances would know.

“This novel is the one that made me feel I should go out and do something—that I should vote for prison reform”

Like the other novels on the list, Kushner’s writing here is distinctive, stylish and well-executed. There are two important trans characters in this novel, too. That theme probably says something about our time: we’ve been thinking about these issues, and what we think about shows up in the novels we read. But, again, they’re not there in order to make a point, or to bludgeon us into thinking about an issue.

Of all the books, this novel is the one that made me feel I should go out and do something—that I should vote for prison reform.

It’s a kind of activist novel.

Yes. But that only works if you don’t feel you’re being manipulated, and with Kushner, you don’t. The world itself has to work, and in The Mars Room, it does. I don’t know anything about women’s prisons, so I couldn’t speak to the reality of it, but it feels very plausible—and worrying—that that’s how it is.

It sounds like an important and chilling tale.

It is. In the novels we’ve talked about so far, there’s some element of facing up to pain and the dark side of life. To make people want to read a book like that, you have to pull something off, because it’s just unrelenting misery.

Fifth, we have The Overstory by Richard Powers. Tell us a bit more about it.

This is the novel whose theme is clearly our relation to the natural environment, in particular to trees as an element of the natural environment.

It’s also a book by someone who clearly loves trees. He loves woods and forests, and trees in cities, and every conceivable kind of tree. He knows a great deal about them, but as you receive that information, you never feel like he found a fact and thought to himself, ‘Oh, I learned this, I can put it in my book.’

What it feels like at the beginning is a series of short stories, each of which has some important thing about a tree or a kind of tree in it, but also holds some human character. They’re all brought together in a marriage which in the end involves a crime and its consequences. The novel’s main sense is that you’re drawn to thinking that trees are wonderful, and we’re doing terrible things to them (and should pull back).

As I said with regard to Kushner’s novel, novels that make you think about issues of public policy don’t work to achieve the effect of making you care if they feel didactic, manipulative or hectoring. And this one doesn’t either. You’d be a very strange person if you came away from this book not caring about what’s happening to the trees.

“You’d be a strange person if you came away from this book not caring about what’s happening to the trees”

You’ve also become engaged with a fantastically rich dramatis personae. There are so many characters in this novel, so many worlds. There are people who start out in China and so on, though the main activity goes on in the United States. It’s beautifully written. He’s a well-established writer, and everybody knows he can write. Like all of these books, it’s very distinctive. In some of the other books, sometimes there’s a spareness of language in certain moments—this is not like that. This is rich language.

It’s also very long. You have to set aside time to read it. When we discussed the longlist with the press, we observed that we felt some of the novels had not been well served by their editors. People took us to be complaining about length—but that’s really not at all what we had in mind. A long book can be exactly the right length. (And this book is exactly the right length, even though it’s very long.) None of the books that we put on the final list was longer or shorter than it should have been.

We are commending to people to read this very long book about trees, but again, there’s an exciting plot, eventually.

Yes, these all seem to be exciting novels, plot-wise, with strong social consciences.

These were the novels we thought were the best, but there were a lot of those. It wasn’t just a reflection of our taste—which it could have been. Many books were well-crafted; they had interesting characters; they had plots that made you want to keep reading and language you just wanted to savour. But they were also making you think about deep questions, often questions of the moment.

There were quite a lot of dystopian novels in the 170: novels worried about what we were doing to the planet, about what we were doing to society, about inequality. Novels that address questions of racial division or questions of gender inequality and sexual harassment. It wasn’t just us picking novels that had messages, as it were. And as I say, having a message by itself can be annoying and tiresome.

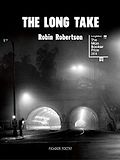

Last, we have The Long Take by Robin Robertson, who’s a poet. He actually describes this book as a “narrative poem” or “novel in verse,” so in that sense it’s very unusual. Why did you include it on the shortlist for a prize for fiction?

It is a poem, mostly. It’s not in rhymed verse; it’s in free verse.

The Long Take has many layers through which it works. The protagonist is essentially somebody who grew up in Canada, goes to the Second World War and ends up first in New York, clearly with what we would now recognise as post-traumatic stress disorder. There are flashbacks to his time in the war. Ultimately, most of his life is a life in Los Angeles.

He arrives in a post-war Los Angeles being torn apart by development. The movie industry is growing; parts of the old town being wiped out and replaced with new buildings. There’s a lot of street poverty, people living on the street, people like him, who have suffered from the war and haven’t really processed it in a way that means they’ve come through unscathed.

The novel is interspersed with images and photographs of the city in this period. It’s about the rise of the movie industry in Hollywood and uses Hollywood techniques—or at least the techniques of sophisticated film-making and great cinema artists, not Blockbuster movies.

Get the weekly Five Books newsletter

On one level, you’re following this man who’s been ruined by the war in some way. He’s a writer and journalist, so he’s also looking into what’s going on. You learn about the city; you learn about the destruction of the old world by the new, post-war world. You learn about how rapacious the business of a growing city is, and how indifferent it is to individuals. In that sense, it’s partly a novel about post-war capitalism.

Because its central social problems are alcoholism, homelessness and poverty, the issues it raises haven’t gone away, even though it’s set in the past. The issue of veterans that haven’t recovered from the psychological trauma of war is very present in the United States. We’ve been at war since 9/11. We’ve had soldiers coming back wounded in part because modern technology, modern medicine, means the number of people who die goes down while the number of people who survive but are wounded goes up. We’re living in a society that doesn’t really want to face the fact it’s at war, despite having huge numbers of wounded warriors.

The novel isn’t about that, but great novels make you think about things in an intense or new way. I admired this book very much. Again, you might say, ‘Oh, you just put a poem on there because you thought it would be edgy and different.’ But it’s on there because we all loved it and we admired it.

It’s a very bold choice.

If you choose verse, you’re operating with an extra formal constraint. It allows you to evoke strong emotions more naturally than prose, in a way. So there are things it makes possible, but it also just imposes constraint. Anybody who reads seriously admires writers who can make the constraints work—who can set themselves a challenge, a formal challenge, and solve it. That’s what makes Robertson a great poet and this a great poem, albeit one which has a long plot.

Would you say every novel on this list sets itself a formal or social challenge, or both, and not only solves it, but also ends up being a testament to the survival of the form?

Yes. As I said, I don’t normally read this many novels in a year. I’m an academic philosopher, so I usually have to read a lot of philosophy—though, on the other hand, it wasn’t odd to pick me; I do read quite a lot of contemporary fiction, and I enjoy reading and thinking about fiction. But I wasn’t sure what I’d feel at the end of this about the state of the novel.

Even though 171 is a huge number, it’s a tiny proportion of the novels published in English in any given year. It’s likely also a small proportion of the good novels published in any year. That makes me feel good, too. These novels are sent to us mostly because their publishers think they’re among the best novels they’ve published. There’s a pre-selection by editors and publishing houses—people who know a lot about this, people who’ve thought deeply about what makes great fiction. It’s a deeply unrepresentative sample in some sense, but if this is what the best ones are looking like, the second-best ones are probably pretty good, too.

I’m not sure there were any that we all hated. There were some I didn’t like very much, for one reason or another. But even the ones I didn’t like, I could see why they’d been sent to us. Every book sent to us—I think there’s literally one exception to this, and I can’t even remember the name of the author—set itself an interesting challenge, and set about solving it. There were no novels where we thought, ‘Okay, this person got up in the morning, wrote the first 300 words that came to their mind, and went about their business, and the next day wrote 300 more words.’ They were novels of ideas. And the best of them were also novels of character, plot and language.

Five Books aims to keep its book recommendations and interviews up to date. If you are the interviewee and would like to update your choice of books (or even just what you say about them) please email us at [email protected]