Before we get to the books, what first attracted you to Herman Melville and his work?

I was assigned Moby-Dick in high school, and as a teenaged traditionalist (an ideology I’ve long since rejected) I was keen to read what I knew was the Great American Novel. Expecting capital-G Genius, I was surprised to find how funny, vulgar, weird, and queer the novel is. Its tone is “strangely compounded of fun and fury,” as Melville writes, and the novel narrates its own messiness as it goes. I loved the weirdness and messiness above all—Melville’s extravagant language and baffling turns of phrase. The more of Melville’s work that I read (on my own, and in college, and then in grad school) the more I felt a deep, agonized sadness and frustration in his writing, behind the goofy puns and dick jokes. It’s the defensive humor of someone who is writing through problems he knows he can’t actually solve: How do we come to knowledge? What is the nature of causality? Is belief naive? Can human connection ever be sufficient to the impermanence and loneliness of the world? The humming restlessness of his writing speaks to me.

Who was Melville?

Herman Melville (1819-1891) was born in New York City to a once-prosperous family. In his early twenties, Melville spent a number of years as a sailor on merchant, whaling, and naval ships. His first novel, Typee (1846), was inspired by his time in the Marquesas after deserting a whale ship. It was a huge success, and Melville further expanded upon his maritime interests in four novels that followed. Moby-Dick (1851), Melville’s epic whaling narrative, was fully appreciated only posthumously. He followed up Moby-Dick with a sentimental incest novel, Pierre, which was a commercial and critical disaster. Other than his now well-known short fiction, like “Bartleby, the Scrivener,” Melville’s subsequent publications gained him little praise and fewer readers. Melville spent the final decades of his life as a custom house inspector, writing poetry. When he died, his final novella, Billy Budd, Sailor (1924), was still unfinished. The Melville revival began in the 1920s after his centenary and shows no sign of slowing down in the wake of his bicentenary.

Let’s turn, then, to Moby-Dick. You recently edited the Oxford edition, which will be published in 2022. Tell us about one of the most well-known, if not the most known, American novels.

In recent decades, many scholars have been committed to reexamining declarations of literary and historical greatness, primacy, or supremacy, recognizing that notions of transcendence have always been rooted in subjective and structural biases. To call a work timeless may be a shorthand for elitist judgments, but it can also suggest how each time period brings a fresh perspective to the text. This is what makes reading Moby-Dick exciting now, whenever your now is.

“The humming restlessness of his writing speaks to me”

Lovers of nature writing may not have seen in Moby-Dick’s cetological chapters an explicit rejection of extractive fossil fuel industries, for instance. But present-day readers can read the novel as attending to natural resource depletion. Ishmael sees “honor and glory” in whaling even as he wonders—in a chapter entitled “Does the Whale’s Magnitude Diminish?—Will He Perish?”—whether “the humped herds of whales,” like the “humped herds of buffalo,” face “speedy extinction.” Ahab’s visible and invisible physical and psychological disabilities have had a new explanatory power within current conversations about disability; Ahab’s wounds in this sense are less deformations or determinants than opportunities for adaptation. Understanding the special violence and horror inherent in whiteness, which Melville writes about at length, has new urgency as critical race theory attends to the historical invention of whiteness and the Black Lives Matter movement calls for renewed attention to structural racism. These examples can go on and on, and I haven’t even talked about the novel’s chapter focusing on homoerotic sperm squeezing as a man’s height of “attainable felicity.”

When you reread Moby-Dick, what is your experience like?

I’m continually discovering phrases and sentences that I had not noticed before, or had not fully assimilated, or had not fully appreciated. Here are some that leapt off the page in my most recent rereadings: “ostentatious smuggling verbalists” (those who borrow/steal the ideas of others); “His pure tight skin was an excellent fit” (a commentary on Starbuck’s tense righteousness); “how I wish I could fist a bit of old-fashioned beef in the forecastle” (Flask’s regret, now that he is an officer, that he can’t eat more casually with the common seamen); “pale loaf-of-bread face” (the hapless steward of the Pequod); and the “anonymous babies” strewn throughout the world by an imagined Lord Whale. I’m also particularly alert to the novel’s riot of odd phrases thanks to a Moby-Dick version of Cards Against Humanity created by Tim Cassedy. As the card game made me realize, there are a surprising number of references to cheese and butter in the novel.

Pierre, your second pick, is Melville’s seventh book. What is it about?

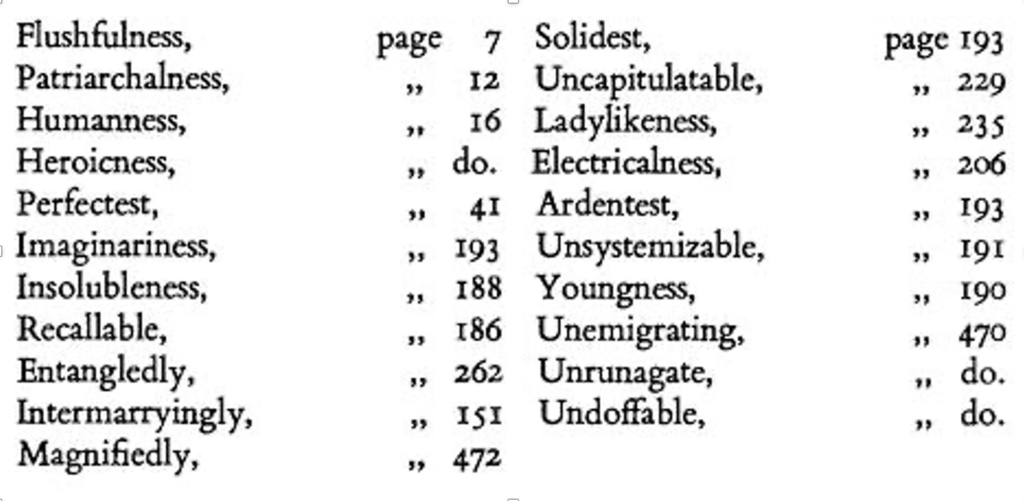

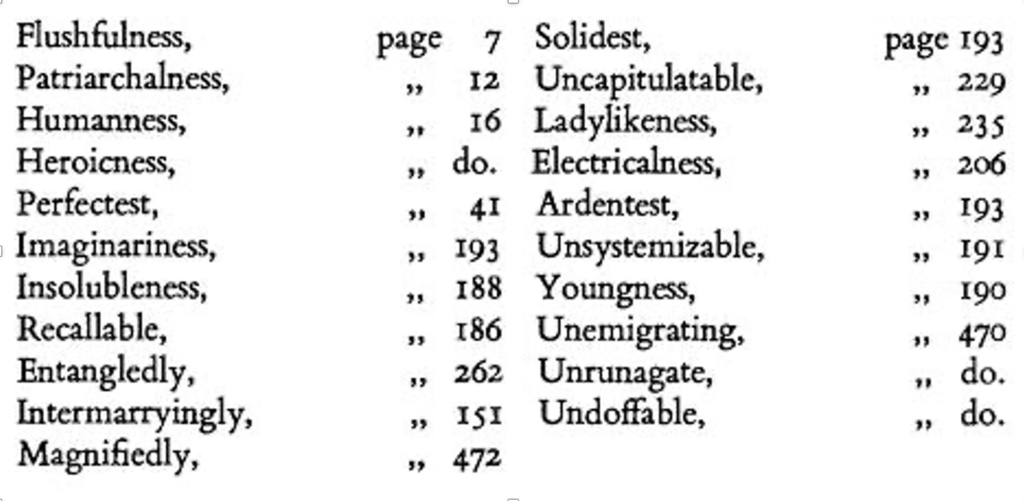

Pierre is so bananas that a contemporary reviewer’s headline read “HERMAN MELVILLE CRAZY.” It’s an incest novel in which the titular Pierre is variously entwined suggestively with his mother, a portrait of his father, his cousin Glen, his half-sister Isabel (whom he pretends is his wife), and his fiancée Lucy (whom he pretends is his cousin). In addition to listing all the made-up words that Melville had inexcusably included in his novel (see image below), another reviewer declared it “A bad book! Affected in dialect, unnatural in conception, repulsive in plot, and inartistic in construction.”

But I could not love the novel more: it’s so densely, perversely strange, so elaborately, bombastically contrarian. The pressures of patriarchal expectation, compulsory heterosexuality, and professional writing have never been so outlandishly portrayed. (Also, see Maurice Sendak’s jaw-dropping and, um, revealing illustrations of a version of Pierre, featured here.)

Next is The Piazza Tales. What can readers expect from these Melville stories?

This volume of short fiction includes three of Melville’s most widely-read works: “Bartleby, The Scrivener,” “Benito Cereno,” and “The Encantadas.” If you last read “Bartleby” in high school, it’s time to revisit it—in an age of economic precarity and the gig economy, it’s a haunting representation of what happens when a worker prefers not to continue with a dehumanizing job. “The Encantadas,” a series of sketches of the Galapagos Islands, feature some of Melville’s most dreamy and meditative writing—it’s gorgeous. And “Benito Cereno” is one of the most amazing and challenging fictions ever written: thorny, mysterious, violent, deceptive. It haunts and harrows a reader, and should.

How does Melville’s shorter fiction, like that found in The Piazza Tales, differ from or compare to the substance and thematic qualities of his novels?

The short fiction features more narrative economy and unity without sacrificing Melville’s still-dazzlingly ornate prose. What I especially love about these stories is how tricksy and untrustworthy the narrators are—it’s hard to get a handle on who is telling the stories, and how their narrative limitations affect how the reader receives the stories. Melville is calling attention to how easy it is to swallow the account given by an authoritative voice, no matter how blinkered, biased, or harmful that voice might be. Throughout his longer novels, too, Melville certainly destabilizes expectations about the narrative voice—most of his novels have first-person narrators whose real name the reader never learns. But in the short fiction this challenge is all the more acute, all the more central to making meaning.

Get the weekly Five Books newsletter

Your fourth selection is C.L.R. James’s Mariners, Renegades and Castaways: The Story of Herman Melville and the World We Live In. This work is described as being “widely influential” and a source of contention in interpreting Captain Ahab. Can you speak to this book and its importance in Melville studies?

In the mid-20th century, C. L. R. James made the brilliant argument that Moby-Dick’s real hero—the novel’s central interest—was not Ahab, or Ishmael, or Moby Dick himself, but the multiracial, multiethnic, multinational crew of the Pequod. In James’s view, Melville imagined (but was not fully able to realize) a novel that elevated and celebrated the polyglot crew over its white officers and white totalitarian captain. James, a Trinidadian intellectual and anti-Stalinist Marxist, wrote Mariners, Renegades and Castaways: The Story of Herman Melville and the World We Live In (1952) while interned on Ellis Island awaiting deportation; he sent a copy of the book to every member of the US Senate. If only they had read it—it resonates still.

Lastly, you chose The Value of Herman Melville by Geoffrey Sanborn. What made you pick this work of criticism?

There are dozens of scholars today who write about Melville’s works with fierce insight and intelligence; Geoffrey Sanborn is one of the best of these, and a critic and scholar whose work I return to again and again. His most recent book does a marvelous job of addressing both new readers of Melville and his longtime scholars—it’s a terrific, accessible, and searingly smart introduction to how to read Melville and how to think about his “value” not as something transcendent, but negotiated by each wave of readers.

Sanborn argues that Moby-Dick—among other works by Melville—were not intended to be “a rigorous, depleting experience” for readers, but instead “a stimulant to thought and feeling.” Would you agree with Sanborn?

Yes. As Sanborn writes in describing the novel’s voice, “What it wants above all else is to be in a meaningful relationship with you, and it will do almost anything—tell jokes, coin words, switch genres, change moods, share dreams, kill characters, hint at blasphemies, fly into rhapsodies, go spinning off into the ether of philosophical speculation—in order to make that happen.” It’s a superb point. In Moby-Dick Melville expostulates “God keep me from ever completing anything. This whole book is but a draught—nay, but the draught of a draught.” In reading Herman Melville’s works, the reader is invited at every stage to join in the collective work of drafting meaning, but always deferring completion. It’s an endlessly productive ferment.

Five Books aims to keep its book recommendations and interviews up to date. If you are the interviewee and would like to update your choice of books (or even just what you say about them) please email us at [email protected]

Five Books interviews are expensive to produce. If you've enjoyed this interview, please support us by donating a small amount.