The history of the American South is our topic today, and your recommendations of the best books to read about it. To start with the simplest question: What is the American South, geographically?

Generally, it’s considered to be the eleven former States of the Confederacy. Going from East to West, it’s Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, Tennessee, Arkansas, and Texas. That’s about a quarter of the continental United States, bigger than most of continental Europe. People often include Kentucky and joke that it joined the Confederacy after the Civil War. That’s the area south of the Ohio River. But, as with everything else in Southern history, the answer to your question is a topic of perennial debate.

Southern Journey, which you wrote, recast the story of the South as one of “settling, unsettling, and resettling.”

My goal in Southern Journey was to have people understand the massive movement of people required to displace the indigenous people who occupied 25 million square miles and to transport individuals held in slavery from one end of the Atlantic all the way to Texas. People lived in the geographic area we call the South for at least 12,000 years. There had long been trade and exchange, as well as warfare and slavery, among the diverse groups of Indigenous Americans who lived in the South. But the story of South, as we think of it today, began with the arrival of English settlers in 1607.

Settlement is a loaded word. It meant the displacement of Indigenous people and replacement by people from Great Britain, which took place over a 250-year period and reached its apogee with what we refer to as “The Trail of Tears” in the 1830s, when the final native groups were driven from their homes in Georgia, Tennessee, and North Carolina to the other side of the Mississippi River. This settler-colonialism fits the pattern seen in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and South Africa. In all those places, native peoples were removed and replaced with copies of British society. That’s settlement.

“I chose Southern history because I thought it was clear that slavery was the great American sin and that we’re not going to be able to move forward until we address that directly”

The unsettling followed the end of slavery, which caused the biggest disruption in American history. There was no compensation for enslavers, nor much help for the formerly enslaved. Between the end of slavery in 1865 and the beginning of World War I, an enormous number of people were moving within the South. During World War I, when the flow of immigrants from Europe stopped and white men left jobs to enlist, factories that needed labor opened their doors wide to African Americans, eager for better jobs up North, where they were not segregated as consistently and violently as in the South. That triggered a Great Migration of Black Americans which lasted into the 1970s. That’s the unsettling.

The resettling started in the 1970s, when several things happened. The South was reconceptualized as the Sun Belt, extending from the Atlantic through Arizona to California. As such, the South became a magnet for settlers of different backgrounds. For the first time in American history, Black Americans chose to move to the South. Also, the South began attracting enormous numbers of immigrants from other parts of the world, especially Latin America and Asia. That’s the resettling part that’s going on.

These massive movements of peoples occurred because of coercion, emancipation, and lots of motivations. Trying to weave all that together is what Southern Journey is about.

What thematic, geographic, and chronological boundaries, usually subdivide Southern history?

Southern history is often considered to begin with the founding of the United States. In the years between 1776 and secession in 1860, a society based on perpetual bondage was built, which fueled the American and much of the Atlantic economy. When people talk about the ‘Old South,’ I point out that at the time of the Civil War, most of Mississippi had only been occupied by white people for 25 years. The South, as a region, comes into being through the system of slavery. The South has been the place where Black people have lived in the largest numbers and in which the social order has been built around containing their presence through segregation and disfranchisement.

Southern Journey is trying to take Southern history out of the containers we put it in. People came tend to do either the Old South or the Civil War or the New South, or Native History or the Civil Rights Movement. All those are part of the same history. I use geography and maps of movement to take history out of its boxes and to set it in motion.

Turning to the books you chose, let’s begin with a book by a giant of your profession, Edmund Morgan’s American Slavery, American Freedom: The Ordeal of Colonial Virginia.

By the time he released this book, Edmund Morgan had been known as a historian of the American Revolution for decades. In exploring the story of Virginia, the true pioneer colony, which began before the Puritans arrived in Plymouth, Morgan is exploring the paradox or the irony of the fact that it was largely slaveholders who wrote the American Revolution’s most eloquent documents about freedom. I’m referring, of course, to Thomas Jefferson, the author of the Declaration of independence and James Madison, the author of the Constitution, both of whom were born as slaveholders and died as slaveholders.

Get the weekly Five Books newsletter

We like to imagine that our history was the history of freedom, and that slavery was a footnote. Morgan turned that upside down. American Slavery, American Freedom argued that it was no accident that the men who wrote these founding documents came from a slave society. He argues that it was because they came from a slave society, in which the working class was marked by their skin color and held in perpetual bondage, that they could imagine freedom for all white people.

The only way that the founders of Virginia could get British people to come here was through indentured servitude. In the 17th century, there was very little chance for young men in Bristol or Liverpool to succeed, so it made sense that they take a ship to the New World. If they survived for seven years as indentured servants, they would get what was called a ‘right of land,’ 50 acres. After generations, the indentured servants, who had supplied so much of the labor in the early years of the Virginia colony, were not enough and were considered too difficult to control. So, they started to tap into the vast Atlantic slavery system.

Historian Nell Painter makes the point that the people of African descent who came in 1619 were indentured people. How does that fit into the story Morgan tells?

Nell is right; the great majority of people in Virginia, in the first decade of settlement, would have been in some form of servitude. One of the great things about American Slavery, American Freedom is that it shows us that it was only after great trial and error that these English people—who had no experience enslaving people, although they had been active in the slave trade—adapted their law, religious practices, and customs for slavery. It took them decades to say, ‘it doesn’t matter if you become Christian, you’re still going to be in bondage.’ It took them decades to settle on the idea that the children born to slaves would be slaves. Laws had to be changed before skin color became a badge of enslavement. It took the English a long time to convert from a world of many kinds of servitude to a system in which African Americans were in perpetual servitude.

Historian Ira Berlin won the Bancroft Prize for your next recommendation. Please tell me about Many Thousands Gone: The First Two Centuries of Slavery in North America.

In the 1970s, a great efflorescence in the study of slavery began which produced a series of great books, among them Roll, Jordan, Roll and Many Thousands Gone. Ira Berlin helps us understand that many tributaries flowed into what became American slavery. After Virginia established this system of slavery, enslaved people were brought into South Carolina, Maryland, and Georgia from many different regions of Africa. Each had a different experience of what it was like to be ripped out of their homes and brought to British North America. Ira Berlin shows us that slavery was a vast and complex system.

In the Presence of Mine Enemies, your 2003 social history of the Civil War, illuminates what the conflict was like for those who lived it. Please tell me about that book.

In the Presence of Mine Enemies is a story of the American Civil War that includes Black and white people, men and women, soldiers, and civilians, and Northerners and Southerners in the same story.

It focuses on two communities in the Shenandoah Valley who were alike in every way, except one. They had the same soil, the same climate, the same ethnicities, the same religions, but there was a line on the ground and south of that line there was slavery and north of that line, there was not. I asked: How could Americans who shared so much have a difference on the issue of freedom which was so great that they would engage in a war that ended up killing the equivalent, if it happened today, of 8 million people? All this was a way to show the human side of the Civil War.

What should one know about the Civil War to understand Southern history?

Everybody knows that slavery ended with the Civil War. But if you read polls today, 40% of Americans still believe the Civil War was caused by a battle over states’ rights. We were taught the Civil War was a conflict between an industrial North and an agrarian South. That’s a gross distortion. At the time of the Civil War, 75% of Northerners were farmers. In 1860, Southern agricultural meant agribusiness based on the bound labor of 4 million people.

Embattled Freedom, by University of Kentucky professor Amy Murrell Taylor, is your next choice.

This book won more prizes than any other book about the Civil War that I know of. Full disclosure, Amy is a former student of mine.

The subtitle of Embattled Freedom is Journeys Through the Civil War’s Slave Refugee Camps. Amy recovered the stories of people fleeing slavery for the protection of the United States Army, with an uncertain future before them. She shows us that two years before the Emancipation Proclamation, enslaved people were risking everything to make themselves free. This moves us from a story where freedom is bestowed on people to a story where freedom is seized by people in slavery.

Would you agree with those who argue that it was the folks in refugee camps and the assistance they rendered to the Northern armies that helped to reorient the Union towards abolition as a goal for the Civil War and to prepare for the needs of freedmen?

There’s no doubt that white Southerners went to war to create a new nation in which slavery would not be challenged. But, at the beginning, white Northerners were not going to war to end the system of slavery. In the beginning of the war, that goal seemed impossible. Slavery accounted for 80% of all American exports. What happens is Lincoln comes to recognize that he can’t defeat the South without defeating slavery. And, as you just suggested, it’s also the case that many Northerners, who had not had contact with Black Southerners, came to know them in these camps and came to see their determination to be free and their capacity for freedom, their hunger for literacy and their resourcefulness. So the refugees helped make emancipation a war aim and prepared the United States to embrace that aim. One of the most astounding things in American history was that Abraham Lincoln was able to persuade the white North to go along with expanding the purpose of the war from putting the United States back together to ending slavery.

The Souls of Black Folk by W.E.B. Du Bois is seminal for so many reasons. Please tell us about the book and its importance to Southern history.

W.E.B. Du Bois, born in Massachusetts, educated at Harvard and in Germany, cast his lot with Black Southerners by moving to Atlanta and relays what he saw here. It’s a series of vignettes. The writing is so powerful.

From the perspective of the white people in Atlanta, he’s no different from the people who’ve been held in 250 years of slavery. He tells a heartbreaking story of when his young son dies in Georgia. He’s walking down the street, with his heartbroken young wife, imagining white people’s disdain for them. He refuses to have his son buried in what he calls the “strangely red” earth of Georgia.

It is Southern history, but it’s also a reflection on the history that shaped what followed its publication in 1903. It is important for its testimony but also for the work on Reconstruction that Du Bois began with this book. He then writes a great book in the 1930s called Black Reconstruction in which he argues that Reconstruction, which was widely considered a failure, showed the promise of a society in which Black people had the opportunity to succeed independently. The Souls of Black Folks is literally pivotal.

Chapter 10 concerns the central role of the church. Maybe it’s Northern prejudice, but I associate the South with deep religious faith. Is there anything unique about the role that religion plays in the South and in Southern history?

People call the South ‘the Bible Belt.’ The South is deeply identified with Black and white evangelical Christianity. Enslaved people were not eager to adopt Christianity until evangelicalism took root, in the late 18th century. Evangelicalism conveyed two things: One, all people are equal in the eyes of God and all people can have salvation through Jesus Christ. Two, the people who suffer the most get special favor in the great beyond. Black people rushed to that message. Then, white Southerners took the message of the Bible and twisted it so slavery was a path toward salvation. You have the paradox of Christianity being both the explanation for why slavery is just, and a great resource for people in slavery.

The Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King taps into that evangelical tradition, pride, patience and determination to launch the Civil Rights Movement. Some argued, like Du Bois, that the Black church was focused too much on eternal salvation and not enough on secular rights. The great accomplishment of Dr. King was to make the church an engine of Black liberation.

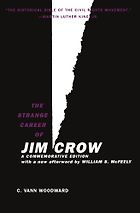

Martin Luther King Jr. called your next choice the “historical Bible of the Civil Rights Movement.” Tell me about C. Vann Woodward’s The Strange Career of Jim Crow.

This is probably the most influential book ever written in Southern history. It began as a series of lectures at the University of Virginia in the 1950s, during the time of segregation. The defenders of segregation in the 1950s talked about it as an inevitable byproduct of two races living together. Woodward said, ‘no, segregation was created only 50 years ago.’ Segregation was not inevitable; it was invented recently and so segregation can be destroyed.

Your book, The Promise of the New South, also corrects misperceptions about what happened after Reconstruction. Can you please tell us about that one?

The Promise of the New South was written in conversation with Woodward’s Origins of the New South, published in 1951. Woodward had told the story of how the early 20th-century South came under the control of demagogic white politicians. I took the very last class Woodward ever taught. When I read this book, my knees grew weak. It was history that read like literature.

The Promise of the New South takes a broader look at the same period. I often ask people, ‘Name something that happened in the American South between the end of Reconstruction and the start of the Civil Rights Movement’, and they’ll just draw a blank. I’ll say, ‘Well, nothing happened except the invention of the most widely recognized brand name in the world, Coca-Cola, the emergence of the most rapidly spreading religious denominations in the world, Pentecostalism, and the invention of America’s only truly original cultural contributions to the world: blues, jazz and country music.

“You have the paradox of Christianity being both the explanation for why slavery is just, and a great resource for people in slavery”

The Promise of the New South was trying to evoke that world. To get down to the ground, I traveled 12,000 miles in a $400 car, staying in motels. I went to every archive I could find and said, ‘I want to see everything you have from 1890 to 1910.’ They’d say, ‘this schoolgirl’s diary?’ I’d say, ‘Oh yeah.’ They’d say, ‘this sharecropper’s account book?’ And I’d say, ‘Gosh, yeah.’ I went through all of these records from folks no one ever heard of to evoke a South that had gotten left out of history books, to include the half of the population that was female and to show that African Americans were not only people to whom things were done, but also people who were creating their own lives and culture. It aims to be a tapestry of life in the South during that period.

You were the president of the University of Richmond. What is it like to live and work in the city that was the capital of the Confederacy and where Southern history is being recast, as activists topple or campaign for the removal of statues of Confederates that once lined its main avenue?

The leading historians of the South, in prior generations, worked outside of the South. During their time, the South was a segregated South. After generations of struggle, the South is different. I’m a native Southerner. I grew up in East Tennessee. Appalachia is an unusual background for an academic. I chose Southern history because I thought it was clear that slavery was the great American sin and that we’re not going to be able to move forward until we address that directly.

Five Books interviews are expensive to produce. If you're enjoying this interview, please support us by donating a small amount.

One reason that I was interested in going to Richmond is because I knew there was important work to be done there. I’ve been an expert witness for Virginia as they considered the removal of the (Confederate commander General Robert E.) Lee monument. If you want your work to matter, be careful what you wish for. As we’re learning now, it turns out the causes of the Civil War and where the cult of the ‘lost cause’ comes from matters a lot.

Since the end of the Civil Rights era, the idea that the North and South were equally abhorrent on race seems to have taken hold on the right and the left. Is this a false equivalence? Is it important to recognize regional differences in history?

Like all people, we interpret the past from where we are today. We’ve come to see that the structures of injustice and the practice of injustice extended across the United States. But if we don’t understand the wellspring of that injustice, we’re not going to be able to address it. And the wellspring of racial injustice lies in the creation of a system of perpetual bondage in the South. Almost all Black people in the United States came through the crucible of slavery in the South. So, to understand the America of today, you must understand the South of the past.

Five Books aims to keep its book recommendations and interviews up to date. If you are the interviewee and would like to update your choice of books (or even just what you say about them) please email us at [email protected]