Tell me about Personal History by Vincent Sheean.

This happens to be one of my favourites. It is an excellent and important book. Sheean was one of the great independent foreign correspondents of the 20th century. This was written when he was a relatively young man in the 1930s. It is a story of the news as he saw it – and felt it. Sheean reported events from his own perspective. He is the centre of the story even when he is not talking about himself. He portrayed himself as a kind of everyman against which the news reverberated.

This book spawned a large number of books of personal history journalism. One of the factors that contributed to the proliferation of these books was the approach of the world war, and communism and fascism emerging as forces in the world. It was a good environment for a book like this. There is a famous Hitchcock film called Foreign Correspondent that is supposed to be based on Personal History, but the script was rewritten so many times that it bears little resemblance to the book, except for the idea that the hero, a correspondent, realises that news is too important to be treated dispassionately, which, of course, is Sheean’s theme in Personal History.

Sheean worked for various newspapers in the US before he decided rather casually to head to Paris in the 1920s. Many young American journalists ventured abroad this way at that time. Sheean started out working for the Chicago Tribune. In one of his assignments it sent him to North Africa where he went behind the lines to find the rebel leader Abd el-Krim in Morocco. He later left the paper and travelled to the Middle East and China, where he fell in love – platonically – with a young American communist. He was always funny about women. He was a wild drinker, smoker and reveller but he was prudish about sex – a fallen away but still tormented Catholic.

Sheean had an uncanny ability to anticipate the news. For example, at the time of Indian independence, he predicted – this is amazing but true, I’ve seen the correspondence and diaries – that Gandhi was going to be assassinated by Hindus. He said, ‘I’m going to go to India to find him.’ He gets a magazine assignment and goes there, taking his time. He attends the opera in Austria on the way and has a wild drunken time in what would become Pakistan. But he gets to Bombay, talks several times with Gandhi, and decides he’ll join Gandhi’s ashram. He was standing right there when Gandhi was assassinated by a Hindu.

Your next book is Red Star Over China by Edgar Snow.

This arguably is the most important book by an American foreign correspondent in the 20th century. At the time it was written in the mid-1930s nobody knew who the communists were. Many thought they were mere bandits. Snow went to the north-west of China to find them. When his book came out the whole equation changed; thereafter communism was understood to be a viable political movement. This had an impact not only in the West but also in China. Snow gave a draft of the book to the Chinese and a lot of young Chinese tucked the book under their arm and decided to go off to the north-west and join the communists.

The book remains a primary source for what was happening at the time. Snow has, for example, the only from-the-horse’s-mouth interview in which Mao talked openly about his life, his background and family. Also, a large number of young Americans read that book and decided to become journalists. The book was a major scoop and such an exciting adventure. Greats like Harrison Salisbury, Seymour Topping and Orville Shell were inspired by this book. It was the All The President’s Men for that generation and made people think, I want to be a journalist. You have to remember that this was a book written under time pressure with no help – that is, there were no files or archives to go to.

Snow describes what he sees in north-west China – the communists had been driven out of south-east China by the nationalists. He noted improvements in education and health care, the egalitarianism, all things that didn’t exist in the rest of the country in the 1930s and that made communism seem very attractive.

Now you’ve got Our Foreign Affairs, Paul Scott Mowrer.

This is a period piece that has been completely forgotten. Mowrer himself is a forgotten journalist, which is too bad, and so to a large extent is his paper. He exemplifies the high quality of foreign reporting on the Chicago Daily News, the paper that more than any other may be credited with creating modern American journalism and foreign correspondence. The paper was owned and run by a public-spirited businessman, Victor Lawson. Among many other innovations, Lawson decided at the end of the 19th century that it was time to fashion a foreign service made up of American correspondents. A lot of the papers hired Brits who were already abroad to write their foreign news, or they might send someone out to run a bureau here or there (typically these correspondents spent a lot of time clipping news from local papers) or send a reporter to do this or that story. But no paper had a professional corps that gathered news in a systematic way. The Daily News wanted to send people out who knew American culture, who were good local reporters, who would get original news.

Mowrer began on the local staff at the Daily News, straight out of high school, and in 1910 was assigned as the Paris bureau chief. He directed the Chicago Daily News war service in France from 1914 to 1918. After the war, he became the chief of the paper’s foreign service. The first Pulitzer Prize in the category of foreign reporting went to Paul Scott Mowrer in the late 1920s. Stories such as he wrote would never win today.

Why not?

Well, he could be a very colourful writer, even literary. In fact, he became poet laureate of New Hampshire late in life. But these stories were dry and somewhat arcane, fit really for the diplomatic pouch, rather than an average reader. Also, there was very little sourcing in his articles – he knew what was happening and didn’t need to get anyone else to say it. He was an expert writing for, if not experts, men and women with a considerable level of interest and knowledge in foreign affairs.

By World War I the Daily News had a quality and reach that gave it great competitive advantage. Many American newspapers subscribed to its service. Its correspondents had address books filled with some of the best sources there were to be had. This carried on after the war, although other papers, especially the New York Times, developed formidable foreign services. Sadly, there is no history of the Chicago Daily News, which, of course, no longer exists today. It went under in the mid-1970s.

Five Books interviews are expensive to produce. If you're enjoying this interview, please support us by donating a small amount.

Mowrer’s book, written in the early 1920s, is an analysis of America’s role in the world after World War I. It is an insightful analysis of the need for America to be an actor in the world, and it shows a brilliant understanding of how the nations were becoming interdependent, not just economically, but culturally and in all kinds of ways. As a measure of Mowrer’s insight, he predicted the oil crisis that would come many decades later.

On the Great Highway by James Creelman.

This is a fun read – a picture of foreign reporting at the end of the 19th century. Creelman wrote for Pulitzer and Hearst. He had adventures, stirred things up and told wonderful stories. Hearst, it appears, sent him to Haiti, where he proposed to the president that his country join the US. This book contains the wonderful canard about Hearst at the end of the 19th century – that he had sent the artist Frederic Remington to Cuba and Remington reported by telegram that there was no war to cover. Hearst is supposed to have said: ‘You furnish the pictures and I’ll furnish the war.’ Hearst never said any such thing. Yellow journalism, as it was called, brought about some good in terms of drawing attention to social ills. But it also resulted in a great deal of entertaining rubbish, such as the Remington story.

What is yellow journalism?

Well, Pulitzer started this Richard F Outcault comic strip in the 1890s called ‘Hogan’s Alley’. The leading character was an urchin with slightly Asian features, jug ears, and a toothy grin – and plenty of high-jinks. Outcault dressed ‘The Yellow Kid’ in a yellow gown. Hearst eventually lured Outcault away from Pulitzer. The crazed-looking urchin became the symbol of the sensational press and gave it its ‘yellow’ name.

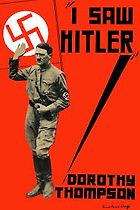

I Saw Hitler by Dorothy Thompson.

This is yet another exemplar of an aspect for foreign correspondence. Dorothy Thompson was a passionate, bigger-than-life journalist, married for a while to Sinclair Lewis. In a very brash way – you had to be brash to be a woman working abroad in those days – she relentlessly hounded the head of the Philadelphia Public Ledger’s foreign service – he was based in France – to hire her. He finally sent her to Vienna on a part-time basis, agreeing to pay her only for what she wrote. In the end she wrote so damn much they put her on staff, as it was cheaper. She later went to Berlin for the paper and then went back to the US, where she initially wrote mostly for magazines like Saturday Evening Post, a magazine with a huge reach that paid very well – if you wanted to talk to Americans the Post was the way to do it.

She often went back to Europe for reporting trips, paying special attention to Germany. In the early 1930s – when Hitler was driving for power but it was not clear he could make it – Thompson wrote this very condescending piece based on an interview with him. It belittled him. She went out of her way to prick the tenderest spots of Hitler’s psyche. She said he didn’t really look like a German leader and how could someone like this ever really succeed. It appeared originally in the Ladies’ Home Journal and then became a book. Of course, she was wrong. He did become the head of state.

Yes, he did.

But it didn’t ruin her career and in a way it helped it – she carved out a role for herself as someone who would say exactly what she thought. She had fearlessly attacked Hitler. She later became a columnist, which was what she was meant to do. She was meant to be a conscience for people. Twice she was fired by newspaper owners for writing columns disagreeing with the management. She was fired from the New York Post in the late 1940s for not fully supporting Israel. She had been pro-Zionist years before, but did not like everything the Israelis were doing.

Get the weekly Five Books newsletter

Anyway, after the Hitler book came out in the early 1930s, Thompson went back to Germany and was expelled by the Nazis. Her expulsion was the beginning of the systematic expulsion of foreign correspondents by governments. Today this is a serious occupational hazard, but this is where it can be said to have begun. Soon it was a regular occurrence in Germany, Italy, and the Soviet Union. Of course, in Africa and the Middle East it’s a big problem now.

Do you get to know Hitler from the book?

Yes, you do. I think the thing that comes across is what a stem-winder he was, going on and on, being demagogic and posing. All of that comes through.

April 27, 2010. Updated: May 17, 2021

Five Books aims to keep its book recommendations and interviews up to date. If you are the interviewee and would like to update your choice of books (or even just what you say about them) please email us at [email protected]