Outside of the Middle East, many people understand Palestine to mean the West Bank and Gaza, and Palestinians as the people living in these areas. But Palestinians who remained in Israel after the creation of the state in 1948 – when some 700,000 were displaced in the Nakba or catastrophe – now make up around 20% of Israel’s population. Could you explain a bit more about this community, and why it has been overlooked?

The difficulty for Palestinians remaining in what becomes Israel after 1948 is that the Palestinian national movement develops in exile, in the occupied territories and the neighboring Arab states. Palestinians in Israel are excluded and shielded from these developments and left in what amounts to a political and social ghetto. Israel strictly circumscribes their understanding of who they are and anything to do with their history, heritage and culture. Israel controls the education system, for instance, and makes it effectively impossible to talk about Palestinian issues there: you can’t discuss what the PLO is or the nakba, for example. This is designed to erode a sense of Palestinian-ness.

For most of the Palestinian minority’s history inside Israel, there’s also a reliance on the Israeli media, which won’t allow discussion of Palestinian identity either. In the state’s early years, Israel does not even refer to Palestinians as Arabs; they are described as ‘the minorities’, purely in sectarian or tribal terms as Muslims, Christians, Druze and Bedouin. It’s an innovation later on that the state recognises them as generic “Arabs”.

Another thing to remember is that the urban, educated middle class is destroyed in 1948. The elites are almost completely expelled. Nazareth is the only city where an urban population survives in any significant numbers. What you are left with is a series of isolated rural peasant communities, and these are not likely to a be the vanguard of a Palestinian national movement. So after 1948 we are already looking at an isolated, severely weakened Palestinian community within Israel, and it is very easy to manipulate this community, to strip it of its identity.

But this system of control starts to break down, first with Israel’s occupation of the West Bank in 1967. That releases the ‘virus’, as some would see it, of Palestinian nationalism to the Palestinians inside Israel. They start to reconnect with people on the “other side” in places like Jenin, Nablus and Ramallah. Families are reunited. Palestinians in Israel begin to realise how much they have been held back, oppressed.

The shift is only reinforced later with Israel’s loss of control over the media. When Arabic satellite television comes along, for example, the state is no longer able to control what its Palestinian citizens hear and see. And Palestinians are provided with an external window both on the ugliness of the occupation and their own situation, and on the centrality of the Palestinian cause to the rest of the Arab world.

So in more recent decades have we seen an increase in the kind of literature that deals with these identity issues? And a change in how these issues are considered?

The greatest problem facing Palestinians inside Israel is how to respond to their situation. They are cut off, isolated, excluded from the centres of power and even from the self-declared identity of a Jewish state. They’re an alien, unwelcome presence within that state. So the question is: how do you respond?

There are two main possibilities: through resistance, whether violent or non-violent, whether military, political, social or literary; or through some form of accommodation. And herein lies the tension. And this is what is especially interesting about the Palestinians in Israel, because to remain sane in this environment they have to adopt both strategies at the same time.

You see this politically in the Israeli Communist Party, the most established of the non-Zionist parties Palestinians vote for. The Communist movement is a Jewish-Arab one, so its Palestinian members are especially exposed to this tension. It is no surprise that some of the leading figures of Palestinian literature and art in Israel have been very prominent in the Communist party. Emile Habiby, for instance, was the editor of the Communist newspaper Al-Ittihad. The tension is obvious in the philosophy of the Communist party, which supports the idea of Jewish-Arab equality but within the framework of a Jewish state. This is a very unusual kind of communism: one that still thinks it’s possible to ascribe an ethnic identity to the state and yet aspire to the principle of equality within it. Palestinian Communists have been struggling with this paradox for a long time.

How successful is the attempt at reconciliation? Is there continued belief in, and support for, a Jewish state?

A central tenet of the Israeli Communist Party is “two states for two peoples”. So who are the “peoples” being referred to? One is the Palestinian people. But what is the other? Is it the Israeli people or the Jewish people? For Israeli Jews at least, it is clearly the Jewish people. In fact, within Israel there is no formally recognised Israeli nationality – only a Jewish nationality and an Arab nationality. The idea of “two states for two peoples” is vague, and it’s meant to be vague to keep Palestinians comfortable within the Israeli Communist Party. But the implication is that we are talking about two states, one for the Palestinians and one for the Jews.

The Communist Party stands for elections as the Democratic Front for Peace and Equality (Hadash). The implication is that peace (a Jewish state) is reconcilable with equality. This is very problematic: the Palestinian intellectuals at the forefront of the party try to evade this contradiction. But you can’t really fudge it, you can’t square the circle.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Emile Habiby ends up writing the quintessential character in Israeli Palestinian literature: Saeed the Pessoptimist. This character represents the tension the minority lives: pessimism imbued with optimism. The Jewish state is the situation you’re trapped in, that’s pessimistic; the optimism looks to the equality you think you can aspire to, despite the reality. Saeed is always trying to square the circle. This very much becomes a theme of Palestinian literature in Israel.

Somebody like the poet Mahmoud Darwish, on the other hand, chooses a side. He does not try to keep a foot in both camps. Darwish says ‘I’m with the resistance’, and he leaves.

Sabri Jiryis also left Israel, after the publication of his book The Arabs in Israel, which is on your list. Could you tell us a bit more about the book, which could perhaps serve as an introduction to the background to this context?

That’s right. The book came out in English in 1976, but in Hebrew it was published in 1966. That is a very important date: it marks the end of the military government, the first 18 years when Israel imposes a system of military rule over its Palestinian citizens, separate from the democratic system that governs the Jewish majority. It is rather like the system of military rule that operates in the occupied territories today. When Jiryis was writing, of course, he didn’t know the military government was about to end, but he produces the definitive book on that period.

Jiryis is a lawyer writing a largely academic book, and it’s the first of its type to be written by a Palestinian inside Israel. Interestingly, like several other prominent Palestinian writers, he chooses to write in Hebrew – as do, for example, Anton Shammas and Sayed Kashua. In resorting to the language of your oppressor, you accommodate. Jiryis is resisting through content, but the language he employs is an accommodation.

He is writing at the close of the military government, and giving a victim’s view of it. It tells the Palestinian side but it is accessible to the Jewish population. So the work is highly subversive. It is also a counterpoint to Jewish academics who are writing books about Palestinians inside Israel in this period, people like Ori Stendal, who works with the intelligence services. The Israeli ‘experts’ studying the minority, and this is true to this day, are mainly working within the security paradigm, trying to understand the threat posed by the ‘Arab Israelis’ and refining the system of control. Jiryis is doing the exact opposite: he is trying to expose and shame the system.

Many of the Palestinians in Israel who write of the horrors of this period end up leaving. We see this, for example, with Fauzi el-Asmar, a Palestinian poet and a contemporary of Jiryis, who is forced out. His writings and activism are subversive, and so the state jails him. In his book To Be an Arab in Israel, he recalls his interrogators telling him ‘We will only make your life easy once you sign this piece of paper to say you’re leaving’. The task here is to get him out of the country, because the last thing Israel wants is people who are defining and shaping an identity for Palestinians within Israel. El-Asmar ends up leaving and becomes an American academic. Jiryis, too, leaves and goes to Lebanon and joins the PLO there. Those who stay but want to keep their integrity keep trying to square the circle: accommodating on one level, while resisting on another.

And I guess this process has the effect of shaping the landscape of Palestinian literature and identity within Israel – making it more accommodating?

More pessoptimist! Nazareth and Haifa are the only two places where a Palestinian middle class, an intellectual elite survived. They had to find some way to be true to themselves as intellectuals, but they also had to find a way to accommodate with the oppressor. And the ways they accomodate are interesting: their subversion is subtle, ironic, and so on. Kashua ends up living among Jews, speaking Hebrew with his kids, half in the Jewish camp and half in the Arab camp, ashamed and proud of his Arabness at the same time. This is the eternal problem of the pessoptimist.

One also has to understand where this comes from: choice. Early figures like Jiryis end up leaving. The process of writing his book seems to resolve in his own mind his status. He confronts the problem of his half-citizenship and rejects it.

So the Jiryis book you have chosen is this book, the book he wrote in Israel before he left. What precisely does he produce before leaving?

He is like a political scientist examining a Kafkaesque situation. He is analysing these absurd laws that look like they are the foundations of a democracy while they are really the walls of a prison. He is trying to explain the paradoxes in the law, and in the wider concept of a Jewish and democratic state. The abuses of the military government simply clarify things.

Take, for example, the Fallow Lands Law, an Ottoman law adopted by Israel that requires landowners to farm their land. If they leave the land untended for more than three years, it can be taken by the ruler and reassigned to those who need it. Under the Ottomans, it is a piece of almost-socialist legislation.

Israel, however, totally subverts the law’s intent. Now the military governor has each Palestinian land owner in his malevolent grip. In this period, no Palestinian resident can leave his or her community without a permit from the military government. So the farmer who needs to get to his land to tend it must either accommodate with the military government (i.e. become a collaborator) or resist and lose his land. In short, he has two awful choices.

As a lawyer, Jiryis is trying to understand how these laws work, how they cohere, how they create a system of control. And he’s really the first Palestinian to try and do that. Another writer, Fauzi el-Asmar embodies the emotional, poetic, artistic response to the situation, but Jiryis grasps the dynamics of it and breaks down the complexity. Really he is describing Israel’s version of Apartheid.

As you said, the book documents the period of military rule, which came to an end in the 1960s. How do you think a reader coming to the book should understand those details in relation to what has happened since, and what the situation is today?

This is one of the things I find interesting about Jiryis. The book is an act of resistance: he was trying to produce a road map that would allow Palestinians to understand the nature of their oppression, so they could be better equipped to fight it. If you don’t understand a problem you can’t fix it, and what Jiryis is trying to do is make the hidden and veiled visible: he’s taking apart the clock to see how all the mechanisms fit. When people understand the system, they can challenge it, try to remake it.

What may not be clear to him when he is writing is whether the system is reformable or needs overthrowing. In the end, Jiryis sides with the military resistance: he goes off and joins the PLO in exile. Although he’s not a fighter, he takes a side. He’s no longer a Palestinian Israeli: he’s simply a Palestinian.

At the same time, though, he’s rooted to the idea of steadfastness, or sumud – this is another feature of Palestinian literature. As soon as Oslo is signed, he returns. In fact, he is the first of the PLO exiles to apply and come back to Israel under the terms of the Oslo Accords. But when he returns, he chooses to live in Fassuta, his ancestral village way up in the north, next to Lebanon. The place is really out in the sticks. But this is where he wants to be: it is his home, his village, his land.

This is very much a response to the peculiarity of Israeli citizenship, which lacks a corresponding Israeli nationality. For most citizens their nationality is Jewish or Arab. That means for Palestinians there is no common nationality that connects them with the Jewish population. And unlike Jewish Israelis, those with Arab nationality have no national rights, only inferior individual rights. In other words, Palestinians in Israel have a very deprived form of citizenship, almost like a guest worker. That creates a very strong feeling of insecurity, impermanence, temporariness: the antithesis of sumud. So they root themselves to a place. Jiryis is a good example of this. I think it is incredible for a man who was such a central figure in the legal establishment of the PLO to come back to the anonymity of Fassuta the first chance he gets.

Perhaps that would be a good time to mention Sayed Kashua’s Let it be Morning?

Sayed Kashua is a great example of the pessoptimist, especially in terms of the way he writes and what he writes about. He has developed a semi-autobiographical character over many years in the Hebrew newspaper Haaretz. He also has the only sitcom on mainstream Israeli TV written by a Palestinian, in which the main character Amjad tries to square the circle: he aspires to live in a Jewish community, to live like a first-class citizen, while constantly fearing that the pretence on which he has constructed his life will be exposed and shattered. Fear of exposure and humiliation drives him. In other hands it would be tragedy, but because Kashua has a wicked sense of humour it is uproariously funny.

It is never quite clear how much Amjad or Kashua’s other characters are really him. He is always playing around with identities, and this is another interesting feature of Palestinian art inside Israel, especially cinema. When reality is so strange, a hybrid documentary style – fact merged with fiction – helps to capture the truth while also offering the protection of distance. Humour does the same. Good cinematic examples of this are films like Hany Abu Assad’s Ford Transit or Eli Suleiman’s Divine Intervention.

Palestinian identity in this context has to be very fluid. One weakness of Jewish academic studies of Palestinians in Israel is that they ascribe the population linear identities. One professor, Sami Smooha, is famous for identity surveys in which he tries to assess whether the minority is becoming ‘more Palestinian’ or ‘more Israeli’. That is really wrong-headed: for Palestinians in Israel there has to be a fluidity of identity to cope with these terribly complex legal, political, emotional situations. And that’s reflected in the character of the pessoptimist.

In Let it be Morning there’s definitely a sense of tension between what the narrator wishes to be the case, and the reality of what’s going on in his life. When he returns from Tel Aviv to the Arab village where he grew up it’s difficult to tell what reality is, and what is coloured by his needs and desires. And the sense of everything slipping out of control is very overwhelming.

Let It Be Morning is unusual for Kashua because it is a serious, nightmarish work – it is the pessoptimist at his very darkest. There is a reason for that: Kashua is writing in the early days of the second intifada when things reached a nadir for Palestinians in Israel. They were living in Israel, often under threat from suicide bombings just like Israeli Jews, but at the same time constantly under suspicion as terrorists themselves from the Jewish population. This is precisely the problem faced by the narrator, a journalist like Kashua working for a Hebrew newspaper and who feels increasingly alienated from his workplace and the Jewish city where he and his family live. He craves a sense of security and so decides to return to his Arab village, right next to the West Bank.

But the relocation offers him no real comfort. He has become too Jewish after a 10-year absence to fit back into the village, torn itself between lingering patriarchal Palestinian traditions and the faux-modernity and materialism its residents aspire to as “half-Israelis”. Their constant accommodations and dependence on their state, Israel, are simply vulgar reminders of the narrator’s own more sophisticated efforts at the same. So the narrator finds himself a “dancing Arab” – the title of his first, seemingly very autobiographical novel – trying to please everyone, and failing dismally.

Survival for Palestinians depends on creativity and adaptability, and a sense of communal cohesion. This is at the heart of the concept of sumud (or steadfastness). But the village is put to an extreme test in Kashua’s book when it is surrounded by tanks and its inhabitants find themselves cut off from the modern world, Israel, and from the old world, Palestine. This is a clear metaphor for the Palestinians inside Israel: they are cut off from both sides. Suddenly the villagers are isolated, and their society and sense of solidarity quickly break down. They stop being a community and become instead competing families, capable of cruelty and inhumanity.

Kashua is playing with a very familiar nightmare scenario for Palestinians inside Israel – the continuing fear of transfer, the threat of being expelled this time, of not holding on to what was kept in 1948. This is something I did not understand until I was living here. There really is a tangible fear that at any moment they and their families could be transferred, that the war of 1948 never finished. This is a large part of the incentive for accommodation: there is a huge sword hanging over your head. You could be expelled; if you put a foot wrong, you could be out the door; the trucks are waiting.

In the book, Kashua seems to communicate an unsureness about the extent to which he’s cooperating or collaborating. The mechanisms and institutions of society are always working towards strengthening themselves. Just by participating in society you are necessarily a part of that, contributing to it. I’ve spoken to many people about this sense, even in the West Bank.

The difference in the Occupied Territories is that for Palestinians there the Israelis are basically the Shin Bet, the army, the police and possibly the settlers – agents of the state. These people appear as unfamiliar, hostile beings. When Palestinians encounter them, it is clearly a master-slave relationship.

Inside Israel it is different. If you are a Palestinian taxi driver in Israel you spend all day speaking Hebrew to people in the back of your cab. You are constantly accommodating, performing as the Good Arab. For most Palestinian youth in Israel this experience arrives as a shock when they start a first job or go to university. They move from a familiar place where all the children around them are like them, speaking Arabic, and then suddenly they are in a world where they are seen as something alien. Often they face hostility, contempt, aggression, subtle or otherwise, from those they must spend time with.

So one thing you often see with Palestinians in Israel is a need to declare their separateness, to make a statement about their identity. That may not necessarily be as a Palestinian; it can be a sectarian identity. So, for example, you see many young Muslim women wearing the hijab, while Christian girls walk around with a cross around their neck. People don’t want to be caught in embarrassing or humiliating situations. It is a way to avoid the danger of being accepted and then rejected, revealed as the Other.

The next book on your list is Hatim Kanaaneh’s A Doctor in Galilee. I guess this gives a very human perspective on some very practical issues and material manifestations of the situation now and historically, obviously through the context of healthcare.

Hatim is a friend, and he sought my opinion on the book while he was drafting it. I find his story, again, illustrative of the problems we’ve been talking about. His family realises he has a talent and they make major sacrifices to send him to Harvard to get a medical degree. This is at the end of the military government, and a very difficult time for Palestinians inside Israel. They are a very isolated community, cut off from the world, barely connected to the transport infrastructure, living in a ghetto, and Hatim makes this incredible leap to go and train as a doctor at Harvard.

Hatim, I think, embodies the qualities of the pessoptimist, even if a very self aware one, one who understands early on that he is trying to square the circle. He has a set of impressive skills, ones denied to other Palestinians in Israel, and acquired because his family suffered to make this possible for him. It is both a huge burden and a considerable weapon. So he wants to put his new skills to good use, to the benefit of his society. The pessimist understands the disastrous circumstances of his community, but the optimist wants to believe his community – and the relationships between Jews and Arabs – can be improved.

He is not simply fixing broken bodies, he is trying to create an infrastructure of public health care for his community. He’s trying to create sewage systems and bring fresh water into the villages, to liberate the inhabitants from the prisons created for them by the state. Israel is a modern country, but it has left the Palestinian villages a hundred years behind. Kanaaneh comes with the tools of modernity to save these villages. The optimist wants to believe this can be done, and that once Israelis see what Palestinians are capable of they will warm to them, see them as human, as equals.

Hatim’s struggle is conducted through the Health Ministry, where he rises to the most senior position ever held by a Palestinian citizen. He assumes he is going to break down the stereotypes, that he will win over the Jews as friends, and that when they revise their opinion of him they will do the same with the rest of the Palestinian minority. He is a man with vision and optimism, but he is trapped in a world that demands pessimism. He starts to see himself more and more as an Uncle Tom and to lose faith in the Jewish colleagues around him. He identifies the racism as so entrenched that he doubts there is a way to circumvent it. He becomes deeply disillusioned. But despite all that he chooses sumud as his act of part-accomodation, part-resistance.

I think the sense of responsibility among people to give back to one’s community is quite common, but in this context the feeling of being ‘unwanted’ within a state structure, so to speak, adds an element of feeling the need to justify one’s own existence. And in the book everything seems pretty hopeless at points. You get a real sense of banging your head against a brick wall.

When Hatim finally quits the Health Ministry, he sets up the first real NGO for Palestinians inside Israel with an international perspective, the Galilee Society. This is an act of subversion. He is trying to bypass Israel and go directly to the international community, because he realises that otherwise no help will be forthcoming from his own state. But at the same time it is not a completely rejectionist stance: he also knows he must work with Jewish society. By reaching out to the international community, he hopes to shame Israel into action.

So the potential for the community to create alternative structures to serve itself is limited, and when it comes to things like infrastructure and healthcare, the state is very necessary. And this makes cooperating and working with the state necessary.

He is resisting by setting up the Galilee Society, but he is also doing it within the framework of accommodation. He’s got a foot in both camps because that is the only option for those who stay. Leaving is a defeat for sumud, for steadfastness. That is why Palestinians see the need to come back to the place where they started: that is the only thing that distinguishes them from other Palestinians, it is the only strength they have.

You’ve also selected So What by Taha Muhammad Ali. It’s a selection of his poetry from 1971-2005. How does this deal with ideas of longing and return?

Taha Muhammad Ali was an internal refugee, or a “present absentee”, this gloriously Orwellian term Israel assigns to those who after 1948 are still present in Israel but absent from their property. Safuriya, his village, which is right next to Nazareth, represents this tension acutely – of presence and absence. Many of the refugees, like Taha’s family, fled to Nazareth and set up their own neighborhood called Safafri that overlooks the old, destroyed village. So they wake up in the morning and open the curtains to look out on the land that they lived on before they were expelled in 1948. He is so present he is almost there, but at the same time he is always absent. This is not an untypical condition: one in four Palestinians in Israel are present absentees.

Here you have another way of looking at the pessoptimist: the present and the absent. The present person is the optimist, the absent person is the pessimist. Some of the best Palestinian poets, including Darwish, were internal refugees, always living with this tension in their being.

Poetry has a very important place in the Palestinians’ artistic pantheon, and it becomes particularly powerful as a vehicle for the Palestinians because it speaks to the whole Arab world. People set poems to music, so it was more than literature, it became part of a wider Arabic culture. It was a way to tell the Palestinian story, the Palestinian sense of loss to the whole Arab world, it was the best kind of newspaper you could have and at the same time gave a sense that the loss of the Palestinian homeland was also a loss for all Arabs, a loss of independence and a sense of self respect that they all shared. Darwish, the most famous Palestinian poet, faces the tension and stays inside Israel for quite a while. But in the end he, like Jiryis, cannot live with it. Taha Muhammad Ali is a pessoptimist. He does not have the heart for pure resistance. He prefers to find the middle ground, some kind of accommodation.

And how is that expressed in the poetry?

Famously he said ‘There is no Israel and there is no Palestine’, which is something you could never imagine Darwish saying. In fact, invariably there is from Taha a rejection of posturing, self-importance and, above all, a deep disquiet at all-consuming hatred, however justified it might seem by circumstance. In one poem,’Twigs’, he focuses on the things he remembers – small things, details like the taste of bread and water. It ends with an assessment that at our death “hate will be / the first thing / to putrefy / within us”. But at the same happiness is never quite present either. One of his lines, used as the title of a great biography in English, is “My happiness bears no relation to happiness”.

There is also a poem, Revenge, where he talks about how he wants to kill the man who stole his family’s home in 1948, thereby “expelling me into a narrow country”. He says “if I were ready – / I would take my revenge!” So for a brief, deceptive moment it seems as though he has found an inner voice of resistance. But in true Taha style he then subverts it all. He recites all the reasons why he would not be able to kill him, such as if the man had loved ones, or friends or even casual acquaintances who might miss him. But even that is not enough of a concession. He also argues that he would leave the man be even if he had no one who cared for or loved him. “Instead I’d be content / to ignore him when I passed him by / on the street – as I / convinced myself / that paying him no attention / in itself was a kind of revenge.” So here is the pessoptimist; a man who starts with grand talk of resistance, but in the end despite himself recognises a need to accommodate, to live with others, to refuse to bow to their level.

Do you think it’s as if there’s a sense of humanity – both in the sense of practical needs and sympathy for others – getting in the way of taking any kind of action?

Taha died a couple of years ago, but there are videos of him on YouTube. You see when he talks, there is a wonderful boylike mischief in his face, a kind of perpetual smile even as he talks about very sad things, the losses endured by himself and his family, and his community. There is an eternal optimism in tiny things: he says “the best drink is water and the best food is bread”. The tiny things in life can give you a great deal of pleasure, and maybe you have to focus on the small things because the big things are too depressing, too overwhelming.

But the day to day is so important because it keeps people going, and it’s also what keeps people accommodating, in a sense.

Taha had four years of formal education because his whole schooling was brought to an end by the Nakba. In 1948 the present absentees lose everything – it is year zero. Taha and his brothers start to rebuild their lives in Nazareth, selling bread from a street trolley. Eventually he opens a souvenir shop next to the Basilica, selling trinkets to tourists, and probably regales them with his stories too. But most of the time there is nothing to do. You can see shop owners like him today, sitting there or dozing or listening to the radio. But you can imagine Taha reading loads of poetry, teaching himself because he understands that only through poetry can he reclaim his voice and reach out to people with his stories.

As a self-taught poet, he finds his own language. Unlike Darwish, he does not use classical Arabic, the heavy, serious Arabic. Instead he uses the street language. He talks to the ordinary man and woman. He does not want poetry to be this big, weighty thing. The subject for him is not the grand Palestinian drama, but the small, inconsequential things that have been lost or destroyed, the efforts to rebuild on the personal scale, to take pleasure in the tiny things that survive. He seeks the reasons for optimism, love and compassion over the urge for hatred and revenge. There is a bitterness too but it must never be allowed to trump what really matters.

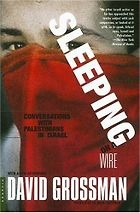

Your final book choice is Sleeping on a Wire, by David Grossman.

I felt we should have one work from an Israeli Jew, because they have done so much to shape Palestinian identity inside Israel. There are some great books on Palestinians in Israel, as well as some truly awful ones. I see David Grossman’s book as interesting because it is really the first attempt to grapple with the Palestinian identity issue in Israel from a Jewish perspective. I do not think it is entirely successful, and I have a problem with his politics, but it is clear he is trying to do it honestly, that he is seeking to understand.

The problem is that he is a liberal Zionist, and there is a constant tension between his liberalism and his Zionism. So the liberal in Grossman wants to understand the trauma that befell the Palestinians in Israel, wants to reach out to them, wants to understand them. But at the same time the Zionist in him fears what their narrative represents. So what happens in each chapter, like a nervous tic, which I find fascinating, is Grossman immersing himself in their stories deeply, allowing them to speak unmediated, but then afterwards he can’t stop himself from interpreting for them, or judging them.

So what’s the structure of this, what form does this take in the book?

It is a very common liberal Zionist position: the need to have the last word, and to create the framework of the narrative. His book is subversive because he is an Israeli Jew giving Palestinians the chance to tell their story, to explain their situation in great depth. He’s very good about letting Palestinians speak clearly and honestly and transparently, you sense that he’s not manipulating the conversations and he’s not editing out stuff, he just wants to hear, he gives you it all. But the context for this act of generosity is a Zionist one. He and his subjects are in a Jewish state, and it has to be one as far as Grossman is concerned. So however much he sympathises with the Palestinians, and however much he understands, however much he feels their pain: sorry, but at the end of the day the Jewish State is more important.

I found the book very frustrating, because he has this great ability to tell his subjects’ stories, but then the narrator, himself, comes in at the end to tell us what we should make of what we have just heard. He cannot leave it to us to make up our own mind; he has to create for us a prism to see through.

This is an important point when we talk about the tension faced by Palestinian Israelis: that profound tensions exist for Israeli Jews too. It’s a hard thing to face, with honesty, the problematic realities of a state that one supports and is a part of. Perhaps this is a different kind of struggle, of individuals coming to terms with the structures of their own privilege, and trying to accommodate difficult truths into a particular vision

.

And I think this is a general problem for Israeli Jews: that the narrative of Palestinians, including or maybe especially those inside Israel, is too overwhelming, too threatening, too disconcerting, too guilt-inducing to cope with. Which is why most Israeli Jews won’t really listen. What is interesting about Grossman is he has enough emotional strength to hear it, but then needs to package it up in a way that he and his readers can cope with.

So do you think the book is valuable as a document of the Palestinian story in Israel, or as an example of attitudes towards that, of Jewish Israeli considerations of the issue?

I think it’s useful as both. Grossman’s motive was probably to write something that, because it was written by an Israeli Jew, would be accessible to people who find it difficult to hear the Palestinian narrative. He hoped to bridge a kind of social divide and help heal wounds.

The book is also a fascinating historical document. One chapter is dedicated to the Islamic movement in its early years, a subject little written about apart from in Arabic. It’s very interesting to see how the Islamic movement saw its role in the early 1990s, caught in a certain moment, at the end of of the first Intifada and just before Oslo. Or the unrecognised villages and their struggle at that time to live in a twilight world of being present and absent in a different sense: on the ground but off the map. Visible to the eye but invisible to Israeli bureaucrats, at least in terms of public services.

Grossman was writing at a moment when Israeli Jews were very pessimistic. Soldiers had been told by their prime minister Yitzhak Rabin to break the bones of Palestinians in the occupied territories to crush the first intifada. It was a time when Israeli Jews were realising that there was serious and organised opposition to the occupation, that their supposed benevolent rule was rejected by Palestinians.

The question of who the Palestinians inside Israel were, and how they were connected to these events, becomes important. Grossman is trying to reach out to the Palestinians in Israel to find some common ground, in the hope of defining an Israeliness. Possibly there’s an element of the security mentality – ‘let’s understand the enemy’. But he is too intelligent and sensitive just to be doing that. He is genuinely trying to find out whether some kind of accommodation can be reached, to ask: are they going to move closer to us, or further away? Because from a Jewish Israeli perspective, the Palestinians inside Israel are seen as the Achilles’ heel of the Jewish state.

At the beginning you alluded to a relatively recent sense of changing and developing Palestinian identity in Israel, through literature, media and so on. How are these books, which explore that, being received? And are things changing in terms of their relationship in wider Israeli society?

It’s an interesting question. Where’s Israeli Jewish society heading? If you look at the Israeli Jewish books about Palestinians in Israel they date from certain periods. In the late 1970s there is a rash of books written as a result of Land Day, when Palestinians in Israel engaged in a major confrontation with the state to stop confiscations of their land. Six demonstrators are killed during the protests. It’s a crisis for both sides: the Palestinians realise their citizenship is not real citizenship; and Israeli Jews appreciate that their rule over this group is contested. The lens through which this is seen is chiefly then a security one. How do we control them better? More books emerge during the 1990s, the Oslo period, because the question then is: what kind of citizenship can a Jewish state concede to the Palestinian minority after a peace agreement? How is the state’s security to be defined? Nowadays it seems to me Israeli Jewish society is much less interested in understanding Palestinians inside Israel.

Why?

I think now they are seen as more of a threat, and the chief interest is how to separate from them, not how to live with them. They are seen as a demographic problem, framed in the language of security. The issue is about “us”: how to protect the Jewish majority. This is the material of policy papers, not books.

Aside from that do you think the issues facing Palestinians within Israel are becoming more important in terms of wider questions about Israel and Palestine, and the possibility of a final settlement?

It is becoming clearer to Israel that Palestinians inside Israel are a key fault line in the peace process. Netanyahu has made the Palestinians’ recognition of Israel as a Jewish state a precondition for an agreement. So in terms of the peace process, Palestinians inside Israel are now a – if not, the – core issue.

During 1948 Israel created a demographic structure – through mass expulsions, and through laws to ensure that only Jews could immigrate – to guarantee that the state was and would remain incontestably Jewish. Now in the current peace talks, what Israel wants from the Palestinian leadership is for them to sign up to this, saying, we’re fine with it. And this is supposed to close the 1948 file, which is still an open file for the Palestinians. And this is why I think Palestinians inside Israel are seen increasingly less as a community in themselves and more as another one of the final status issues. The Palestinians’ fight inside Israel for equality and democracy ultimately risks creating a right of return – because real equality requires that Palestinians have the same rights of naturalisation as Jews enjoy under the Law of Return. And then you would have refugees returning and Israel’s Jewish majority being eroded.

And this puts another layer onto what you mentioned about accommodation: that’s a very big question resting on the shoulders of Palestinians in Israel. Yet as I mentioned earlier, I have the sense the reality of Palestinians living within Israel is not really recognised widely. When outsiders are introduced to the reality for the first time, they tend to find it puts everything in a very new perspective.

And it’s overwhelming. It’s overwhelming for everybody. The reason Grossman is reframing all the time is because it is overwhelming. The reason Sabri Jiryis and Mahmoud Darwish leave is because it’s overwhelming. The reason Taha Muhammad Ali and Sayed Kashua adopt the pessoptimist worldview is because it’s overwhelming. The reason Hatim Kanaaneh digs in his roots as deep as he can is because it’s overwhelming. And for outsiders it is overwhelming too; the reality is more complex and more paradoxical and more entrenched and more irreconcilable than anyone could have imagined.

It’s not just a case of drawing a better border. It’s much more complicated than that. It’s redressing decades and decades of injustice, and in doing so maybe creating new injustices. Because so many Jewish immigrants came and settled here and gave up lives elsewhere. What happens to them? You can’t just create a new set of injustices. How do you reconcile these problems? How do you square all these circles?

Five Books aims to keep its book recommendations and interviews up to date. If you are the interviewee and would like to update your choice of books (or even just what you say about them) please email us at [email protected]

Five Books interviews are expensive to produce. If you've enjoyed this interview, please support us by donating a small amount.