Before we get on to the books, can you just very briefly say what the Holy Roman Empire was and why it’s still an important thing to study now?

The Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation was a unique political entity that is not well known about, even in Germany. In history classes, you won’t learn anything about this political entity because it doesn’t match the nationalist narrative that was shaped by 19th century historians of ‘Kleindeutschland’ — the ‘Lesser Germany’ of the Second, Bismarckian Empire. The Holy Roman Empire did not fit into this picture, and so it was more or less neglected, and is still today, to some extent.

The Holy Roman Empire dates back to the Middle Ages, but took more shape around 1500. It was a loose federation of very different members, originally united only by the bond of fealty to the Emperor as the head of the political body. What characterizes this kind of federation is the heterogeneity of its members: from great princes secular and ecclesiastical, to imperial counts, prelates, and cities. This heterogeneity was also the challenge in keeping the Empire together.

During the early modern period, this very loose medieval political body took on a clearer institutional shape through a couple of common institutions, such as more frequent Imperial Diets, the Imperial Aulic Council (Reichshofrat), the Imperial Chamber Court (Reichskammergericht), imperial taxes (Türkensteuern) and a couple of other ways to manage this heterogeneous alliance. The political bonds were weakened during the 18th century because some of the great princes became monarchs of territories outside the Empire, like the Prince-Elector of Brandenburg, who became King of Prussia, or the Prince-Elector of Hanover, who became King of England. The Emperor himself, the Archduke of Austria, was also King of Hungary and Bohemia, which did not belong to the imperial federation either. This overstressed the cohesion of the whole and finally, it was Napoleon and the Napoleonic wars that led to its ultimate dissolution.

I knew that it was Napoleon who dissolved it, but you’re saying it was on its way out, even before he came and gave it the coup de grace?

Yes. The forces of dissolution, in a way, characterized the whole alliance from the very beginning. But the imbalance between the weaker, small principalities and the very powerful princes became stronger and stronger. Finally, the Emperor dissolved the Empire with a stroke of his pen, responding to Napoleon’s ultimatum.

We’ll come on to this soon, I’m sure, when we discuss some of the books. Did the courts that you mentioned, and the Imperial Diet, all survive the impact of the religious division at the Reformation?

The Reformation and its aftermath really shaped the character of this political body, because when it became clear that no denominational side was able to annihilate the other one, they had to find procedures to cope with this confessional diversity. These procedures were codified in so-called Fundamental Imperial Laws (Reichsgrundgesetze or leges fundamentales) that established ways of peaceful coexistence and characterized the structure of the Empire from the 16th to the end of the 18th century – though with the deep rupture of the Thirty Years War. It is important to keep in mind that religion, at the time, was not just about individual belief, but was closely intertwined with politics and economy. It touched on property rights. Bishops were princes of ecclesiastical principalities, for example. So, you could not separate church structures from political and economic structures. This is why the Reformation was so extremely challenging but at the same time paved the way for institutional reforms. I would argue that, in a way, it has shaped the political structure of Germany until today, not only the federal structure, but also the way the state copes with confessional diversity.

Let’s turn to the books you’ve chosen. First up is Peter Wilson, The Holy Roman Empire: A Thousand Years of Europe’s History. It sounds like it’s probably the one book you need.

Yes. Peter Wilson is one of the best British experts of German history, and this book is a masterpiece. All of the reviews praised this book for its thematic breadth and chronological scope. It is very unusual to describe the history of the Holy Roman Empire from its medieval beginnings to its dissolution in 1806.

It is a challenge, of course, for a non-medievalist to tell an overarching story of the medieval and early modern Empire, and it is all the more challenging because Peter Wilson does not follow a chronological order. He has a huge section called the “Ideal.” It was more or less the myth of continuity that constituted the identity of ‘the Empire’ over time. There was very little structural continuity, he argues. Then there is a section about belonging and borders, a section on governance, one on society, and finally a chapter on the afterlife of the Empire. That can make it difficult to navigate through the book, because you don’t have a chronological narrative. But it is very illuminating and inspiring. The book is extremely detailed and elaborate–really admirable.

“This book is a masterpiece”

What also makes it unique, I think, is that it is about Europe’s history, not just German history. The Empire comprised far more regions than what we know as Germany in the 19th century, not to mention the present Federal Republic. Peter Wilson also makes very clear how fluid the character of the federation was. There weren’t even territorial borders in the strict, modern sense. One might say that he downplays the turning point around 1500, which was a landmark, because, as I said, there were a couple of reforms that established an institutionally stable order that did not exist in the Middle Ages. Maybe he downplays this a little bit too much—I think that would be the criticism of medievalists and early modernists.

Another thing I really like about the book is that he does not tell this old nationalistic story about the great medieval times and then the decline in the early modern period. This is the old nationalist narrative he does not repeat. But nor does he make the opposite mistake of romanticizing the early modern empire and describing it as an order of peace, tolerance, rule of law and so forth. Since he is British, he has a sober and distanced view on the Empire, which makes it all the more valuable for German readers.

Let’s move on to Lyndal Roper’s Martin Luther: Renegade and Prophet. Tell us about this one and, in particular, why you’ve chosen it to illustrate something about the Holy Roman Empire.

The Reformation era in general and Martin Luther in particular are absolutely decisive for the history of the Holy Roman Empire and beyond. And Lyndal Roper approaches the man Luther from the perspective of gender history. She is not just a historian of gender, but of the body, and also of witchcraft, as well as the Reformation. So, she has a very original perspective, different from how many church historians would describe Luther and the evangelical movement. The biography goes far beyond the history of theology or church history, although she includes these as well—she is an expert on Protestant theology—and this makes the book particularly valuable.

She looks at the man Luther from the perspective of his body. She describes his physical suffering, his diseases, his emotions. She reads his innumerable letters that contain, for example, descriptions of his dreams, which are very telling. She writes a lot about his marriage, his personal relationships, his anger, his anxieties. And about his hatred of Jews. She does not downplay this in any way, but describes it in very sharp terms. She is interested in his sexuality.

What makes it special is that she is able to connect his personal, physical and emotional life to his theology and his plans for Church reform, showing that these are closely intertwined. For example, take his marriage to a former nun, which was an absolute taboo and a breach of one of the Church’s most fundamental norms. Lyndal Roper shows why and how this transformed Christian anthropology.

She’s also interested in his conflicted character, and in his flaws, and his idiosyncrasies. From the perspective of gender history and the history of the body, she sheds new light on this person, but also on his times. Since the Reformation is so crucial for the political, economic, and social history of the early modern Holy Roman Empire, I put it on my list, because it is far more than just a biography.

Let’s move on to David M. Luebke’s The Empire’s Reformations: Politics and Religion in Germany 1495-1648.

David Luebke covers the time span from around 1500 to the end of the Peace of Westphalia, including the Thirty Years War. His first books were about the communal level, the peasants, their ways of rebellion or opposition, but also on religious coexistence from a micro-historical, local perspective. In this book he brings his knowledge of this local level to describe the Empire, its confessional structure and its political history, from the bottom up. It is a very concise, brief, comprehensive book on this era, 1500 to 1648, between the two landmarks that shaped what one can call the Imperial Constitution.

Again, religious and political history can absolutely not be separated from one another. He describes the Reformations in the plural, Luther’s and Calvin’s movements, but also the Catholic reform. The Reformation did not produce distinct denominations immediately. What historians call ‘confessionalization’ was a complex, nonlinear process. In the end, there were three distinct denominational groups in the Empire—Lutherans, Calvinists and Catholics—but their emergence was a very long and complicated process. History is always contingent. It could have happened completely differently andnd this is what becomes clear in this book.

David Luebke shows how religious diversity posed a threat to the political and economic order and to the tranquility of society. Society was rigidly hierarchical, and this hierarchy was challenged in a strong way. The question is, how did princes and local communities manage this unrest, and how did the different religious and political reformations contribute to general transformations like state building at the level of the individual principalities? At the same time, he looks at how these changes influenced the loose connection of the members at the Imperial level. You always have to take into account that there were at least three layers: the local level of the communities, the territorial level of the principalities, and the top level of the Empire as a whole. You always have to describe the interrelations between these different levels. And this is what he does in a very concise way. He also shows how the Empire differed structurally from other European monarchies, like France, because of this multi-layered structure.

This ends at the Peace of Westphalia. Did the Peace of Westphalia rebase the Empire politically? Or did it restore something that had existed before?

It restored, in a way, after the Thirty Years War, what had already been achieved in 1555 at the Peace of Augsburg, but on a different level. After this catastrophic war, the peace treaties had a stabilizing effect. The Peace of Westphalia was a fundamental law for the Empire as well as for the international order.

However, it also created a problem for the subsequent centuries, because it made the imperial system less flexible and conflicts less manageable. It fixed all of the members’ vested rights and a certain denominational status quo without settling the basic tension between the imperial bonds on the one hand and the princes’ claim to sovereignty on the other. This left little means to react flexibly to changing conditions, which was a huge handicap for the future and contributed to the slow but steady dissolution of the whole imperial system.

Let’s move on to Europe’s Tragedy: A New History of the Thirty Years War. I’d always assumed that the 30 Years War was primarily a confessional conflict. But I think Peter Wilson argues that it was more to do with the constitution of the Empire. Is that right?

Absolutely. Confessional diversity was a crucial feature of the Empire, but this does not mean that this war was just about religion, because, as I already mentioned, religion was inseparable from the social, political and economic order. There were severe political consequences if, for example, a prince changed his religious denomination. I think this is a very general pre-modern characteristic. Today we are used to separating social fields such as religion, economy, politics, law, science, etc., all of them following their own, distinct social logic. However, this is a modern phenomenon. These fields were not separable in the early modern period. And this is something that historians in the 19th century very often did not realize or take into account.

Peter Wilson’s book is 1,200 pages or so. It is extremely detailed. You can find every political and military event, but also structural features that are very important, like how the military was organized. And the book is not just about the Thirty Years War as such, but includes the time before 1618, the preconditions, the structures, the complex beginnings of this war, as well as its aftermath and structural consequences.

“It was not just one war, but a complex bundle of conflicts that were all interrelated”

He calls it “Europe’s Tragedy.” It is not just about Germany, although contemporaries called the Thirty Years War ‘Der Teutsche Krieg’—the German War—because it took place on German territory and the German-speaking lands were affected most, some regions more than others. But Wilson tries to show how everything was connected to everything else. It was not just one war, but a complex bundle of conflicts that were all interrelated. The war was a European event (or series of events), since almost all foreign powers were more or less involved, not only Sweden and France that intervened directly. The European ‘society of princes’ and the imperial order were deeply intertwined, since European sovereigns such as the king of Denmark were at the same time members of the Empire. Peter Wilson makes clear that the war was also a conflict about the Imperial Constitution, the power of the Emperor and the autonomy of the imperial members. All of this was entangled with political conflicts that had begun before 1618 and others that were not finished in 1648, so you can even argue that it was not just a 30-year war, but a much longer conflict.

Peter Wilson also shows that it was not primarily a religious war. The troops were called Swedish, or French, or the Emperor’s troops, but not Catholic or Protestant troops. There were soldiers fighting alongside each other from all different denominations. He also shows that the war was not inevitable. There were certain moments in the course of this war when it could have been ended, but then something happened that made it carry on. I think it is important for historians to make clear that history is always contingent. Nothing is inevitable; everything could have happened differently.

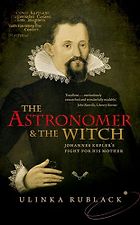

Let’s turn to your final book, Ulinka Rublack’s The Astronomer and the Witch: Johannes Kepler’s Fight for his Mother. This is more of a micro history, right?

I wanted to include something from the field of history of science and magic. You could say this is not a book on the Holy Roman Empire as such, but it is very characteristic of another way of writing history, on the basis of legal proceedings. Especially in the early modern period, it is very difficult to grasp what common people did or thought, but legal proceedings are a very valuable source for giving us a glimpse.

This is really an ingenious idea to thematize Johannes Kepler, one of the most famous astronomers of all time—next to Copernicus, a big actor in what we call the Scientific Revolution, who discovered the laws of planetary motion. Every school kid will have heard his name at least once.

What is less well known is that Kepler’s widowed mother was accused of being a witch in 1620. So, Kepler gave up his research for some time and took over the legal defence of his mother. This is an extremely interesting case, because, on the one hand, it is about witchcraft and the way the legal proceedings worked. On the other hand, it is about Kepler, who used all his methodological skills, his new ways of producing scientific knowledge, to defend his mother.

What’s really stunning is that he either believed in witchcraft, or, if he didn’t believe in it, he didn’t call it into question. So, he reckoned with the possibility that there was something like witchcraft, but he tried to prove why, in the case of his mother, it wasn’t involved. This shows something very important about what we are used to calling the Scientific Revolution, namely, that in early modern times, you could not separate magic from science. Actually, what we today would call experimental science was called ‘natural magic’ then. It is only with hindsight that you can distinguish what proved to be scientific knowledge and what proved later to be superstition. A lot of recipes—what we would today call medicine or pharmacy—were then considered to be a kind of magic knowledge.

This interrelatedness of what we call magic and what we call science is very nicely shown in the book by Kepler’s arguments. The book also does justice to his mother, who represents a characteristic figure of the time, the wise woman who had this specific knowledge of healing, a role that became almost extinct in the process of the professionalization of medicine in the late 18th and 19th centuries.

The book is also a very good read, fascinating like a criminal story. Ulinka Rublack is the only German among my four authors. She is an expert of the Reformation era as well as a historian of gender, of fashion and of the art market, so she looks at the Empire with a very different perspective than the others.

And did Johannes Kepler get his mother off the hook?

Yes. She was not condemned as a witch in the end but died shortly after the trial.

Finally, Barbara, tell us about your Maria Theresa biography, what you were seeking to demonstrate or achieve with that book.

Maria Theresa was born in 1717 and died in 1780, so her life span covered almost the whole 18th century. She is a very famous figure, part of the Austrian national narrative as well as the Habsburg imperial narrative. For me, she was interesting as a key figure to the whole century, and writing her biography gave me the opportunity to describe a lot of things that I find interesting about the 18th century, which is not only the Age of Enlightenment, but also the late Baroque period. Maria Theresa mirrors in her life and her reign the ambiguous, even contradictory character of the whole century. So, you can see her as an enlightened monarch in many ways, but you can also consider her a traditional Baroque ruler.

To be honest, I don’t really like her. As a very strict defender of the one and only true Catholic faith, she persecuted the Protestants. And she expelled the Jews from Bohemia. So, she was radically intolerant on the one hand, but on the other she was, in some respects, an enlightened ruler, too. She fought, for example, the belief in vampires that was flourishing in her territories at the time. In her old age, she even considered abolishing serfdom in Bohemia. There are a lot of features that, from the present point of view, seem contradictory.

She is also an interesting figure in gender history. She was the heir of the Habsburg lands, which was quite unusual for a woman. She ruled her territories herself, which nobody had expected. She was also the mother of 16 children. Being a woman, a mother, and a sovereign ruler, she challenged the gender order of the time. It is fascinating how she managed this complicated situation. She had to defend her territories against a lot of enemies—Frederick II of Prussia was by no means the only one—and she did so quite successfully, which nobody would have expected.

She is not only an interesting figure in herself but also a key to understanding things like, how a court functioned, and what the social logic of the time was like. She helps to understand the conflict between enlightened ideas and Baroque religiosity, the changing relationship between church and state, but also, for example, how warfare changed during this period or how new media emerged. Her family life is also interesting, the rigid way she controlled her adult kids, the mercilessness with which she sacrificed her daughters to the dynastic principle, such as Marie Antoinette or Maria Carolina. The book is also about the history of sexuality, the history of the body, the history of clothing; all of this can be explored through Maria Theresa. It is a kind of all-encompassing history of the 18th century through the lens of this individual’s biography.

How did her role as a woman conflict with her role as a queen regnant? What could she or couldn’t she do that she could or couldn’t have done if she had been a king?

She couldn’t wage war. She was almost always pregnant. This was, of course, a handicap, but the most important thing was that her enemies denied her legitimacy from the very beginning, when she ascended to the throne. A female ruler was considered a ‘state disease’, and that gave her dynastic rivals a welcome pretext to invade her countries.

Was that the War of the Austrian Succession?

Exactly. The female rule was just a pretext; the weakness of her predecessor’s rule was a more important reason. But the common belief that women are inferior to men in body, mind and soul made it easier to legitimize the attack. Interestingly, at her coronation—she was queen of Bohemia and of Hungary—she was crowned in a very elaborate ritual, as King of Bohemia and King of Hungary. She underwent a male ritual, riding on horseback and wielding the sword against the enemies of Christendom. The master of ceremonies explicitly said that as the heir to the throne, she was being treated and regarded as a man. So, her female body was distinguished from her male political role. This is very telling about the way one coped with this challenge in the 18th century. She was defined as a male person, although she gave birth to 16 kids.

Who was her husband?

Her father had chosen her husband, Francis Stephen of Lorraine. He had lost his own principality and dynastic power, so there was no rivalry between the two houses, and he was absolutely dependent on her. Everyone expected him to take up the government and actually to rule. But she disappointed all these expectations and ruled herself, which was very unusual.

He was some sort of cousin of hers, was he?

They were cousins, since all of the European dynasties were closely related. But these two grew up together, which was very uncommon. Noble couples usually met for the first time at their wedding. Some intimate love letters have been preserved, so it seems that she really loved him, which was extremely unusual. Contemporaries said that they behaved like peasants, sleeping in the same bed.

Five Books aims to keep its book recommendations and interviews up to date. If you are the interviewee and would like to update your choice of books (or even just what you say about them) please email us at [email protected]

Five Books interviews are expensive to produce. If you've enjoyed this interview, please support us by donating a small amount.