This year, 2018, is a centenary celebrating the independence of the Baltic States: Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia. Are there common themes, or tone, of the contemporary literature from these three countries?

I’ve been asked many times to try and draw out some similarities between the literature of these three countries. Generally, though, I see more differences than similarities. Working as a literary agent for the Latvian Literature platform, I’ve been motivated to work more towards finding what makes Latvian literature unique, what makes it stand apart. Maybe that’s why I see more differences than similarities, by and large.

“Now that people aren’t so close to it anymore, we can get a slightly different perspective on the history of the not-so-distant past”

Having said that, if you wanted to draw some sort of parallel, one thing happening in the literary scene of every Baltic country at the moment is a certain reappraisal of the Soviet past on some level—specifically, beginning in the 1960s and through to the 80s. Those moments of reappraisal can be seen happening periodically in poetry and in fiction throughout the last 25 years. Now that people aren’t so close to it anymore, we can get a slightly different perspective on the history of the not-so-distant past.

Aside from this common thread, however, in terms of trends, I believe you have one or two very characteristic features in the literature of each Baltic country, some sort of genre that you don’t really find in the others.

Let’s start with Latvia. You’ve chosen Soviet Milk, or Mother’s Milk as it was originally titled in Latvian. It very much is an example of the trend you described, of coming to terms with one’s Soviet past. It’s presented to the reader in a poetic alternation of voices between mother and daughter, tracing the recent past right into the present. It was a critical success not just in Latvia, but across the Baltic states. Why do so many people across the region relate to this story?

It was also published not too long ago in Estonian and is still considered to be in the top 10, from what I understand. Right away, it was a big hit. People have been talking about it and are still writing reviews and articles about it.

For readers from Western Europe, I think it’s a book that really sums up the Soviet experience. Especially regarding the latter half of the Soviet occupation. Moreover, I think the story—a mother/daughter relationship—is universal. From my perspective, it’s actually the most important aspect of the book.

Essentially, the general arc of the story centers on a medical researcher and her daughter. For various reasons, after some time spent in Leningrad (where she was working), she is sent back to the countryside in Latvia. She lives there together with her daughter, who has a very difficult time understanding why her mother acts the way she does.

The mother doesn’t feel that she has any motherly instincts, hence the title of the book. We observe them living together, through the 70s and 80s, as the mother has a very difficult time simply living life. You could say that she has some form of depression. Throughout the novel, this relationship between mother and daughter gets worked and reworked, from the daughter’s point of view—the perspective of a younger generation—as well as the mother’s.

All the while their relationship unfolds against the backdrop of historical events in the Soviet Union. The mother is very anti-Communist; the daughter is raised in a milieu that considers Soviet power to be bad. From her own personal experience, however, attending school and growing up, she doesn’t see anything bad about it. Only later as she matures does she start to understand some of her mother’s beliefs, what her mother was saying about the regime.

This dichotomy pervades the story. The perspectival shifts between mother and daughter, right down to the narrative voice, are brilliantly executed by Nora Ikstena. These two perspectives are so very different. We identify at first with the mother; sensing her voice coming through, we come to believe in her. Then the reader grows to realize that we’re really seeing everything through the daughter’s eyes. Ikstena’s writing is tremendously skillful.

Grandparents feature in the story as well. I found the way the different generational perspectives are presented to us in some ways presages political difficulties that a country like Latvia has been wrestling with since independence, in contemporary society. How do we reconcile these different visions—or this understanding of our political inheritance—across generations? Especially when the Soviet ideology, as you described, is on the one hand regarded as redeeming, and on the other considered somehow imprisoning, or empty.

The characters of the grandparents we can very much recognise among older members of Latvian society today. If I go meet somebody’s parents (or older individuals generally) today, for example, these characters from Ikstena’s book come alive.

On some level, you can probably see similar attitudes to this across the former Eastern bloc. From a more universal perspective, generations change everywhere, and each is affected differently by historical circumstance. In the former Soviet Union, however, there was a major historical break when the USSR fell apart. Many of my local friends—people who are now in their 30s, let’s say—talk about how their parents are afraid of new things. They were the parents who grew up ideologically pure; they were post-war kids. In the new environment, these are people that are very afraid to do anything out of line.

Five Books interviews are expensive to produce. If you're enjoying this interview, please support us by donating a small amount.

There was tremendous conformism under the Soviets. You were just supposed to follow the party line and not do anything unorthodox, because if you did, the consequences could be dire. There’s a distinction between the immediate postwar generation and people who were born before World War II. They certainly endured hardship, but their attitude to authority—to the state—is very different.

Interestingly, their grandchildren (people that grew up in the 1980’s, and certainly those born after 1990), have almost come full circle in their attitudes. They almost have their grandparents’ views on some level. Ikstena’s book echoes this in the way that the character of the daughter can relate more closely to her grandparents than to her own mother, definitely something that is very much a part of the fabric of contemporary Baltic society.

That leads quite nicely to a discussion of Jānis Joņevs’s book. It’s set in the ’90s and almost reads like young adult fiction. Heavy metal—doom metal, no less—is used as a prism to refract a glimpse of this transitional moment, from a Soviet regime to a new regime. Across Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union, music was often a form of resistance and also cultural aspiration. It’s amusing that Joņevs should choose doom metal as this vehicle to talk about what was happening in society at the time. Music was key, however. As an aside, the only statue of Frank Zappa anywhere in the world is a bust just outside the city centre in Vilnius. It highlights perhaps the extent to which music was a form of cultural resistance.

I’m finding, especially in this centenary year, there are many interviews with people who were major musicians in the late 1980s, beginning of the 90s. They are seen as very important people not simply for being musicians, but for having the courage to bring ideas about independence and political freedom into their work.

There was as music group, the Lithuanian rock band Antis, who are still performing today. Early on, they began to gain a lot of media attention. People started coming en masse to their concerts, followed closely by the police, of course, as they were seen as a disruptive force. There was a Lithuanian documentary film that came out not too long ago called How We Played the Revolution, which talks a lot about what they were doing, and how important music was at that time. This was a very public form of resistance. People saw that expression was possible.

When I talk with Estonian friends, they’ve also mentioned a few groups that were saying things in their music that at the time you couldn’t—really shouldn’t—say. It’s no coincidence that in the history of the Baltic States, national song festivals were an integral part of the national awakening. Music has very much played a role in the identity of Estonians, Latvians, and Lithuanians, and also what they came to think was politically possible in the late stages of the Soviet Union.

These were the singing revolutions, after all.

Exactly! Jānis Joņevs’s is a coming of age story, and the coming of age of the protagonist is very much a metaphor for the coming of age of the country, you could say. He tells us how in those early 1990s conditions, it was all a bit wild still. The Iron Curtain had collapsed, but these did not become democratic states all at once.

I don’t think people realise just how much of a Wild West it was in the early 90s. You had a lot of very murky business dealings. You had bombs going off; you had assassinations in broad daylight—not of political figures, but of business figures. At the time, there was a real lack of clarity about where the country was going, something Joņevs really draws out. It was a confusing place to grow up as a teenager.

Let’s move on to Lithuania, and start here with the younger of the two authors that you selected, Aušra Kaziliūnaitė. I was reminded in reading these poems not only how often slightly surreal, poetic, magical imagery recurs in Lithuanian folklore, but also how that’s also carried over into modern culture. There was a lot of what you might describe as folkloric or certainly animistic imagery in her poetry that, to me at least, gave it a very Lithuanian touch.

Well, she has opportunities to read widely. It’s not all the same references as you might see, for example, in the Soviet period, where you had a lot of things having to do with animistic nature. You could talk about nature. It was allowed. And thereby you could address political themes without being direct. People understood the symbols, people understood what the poets wanted to say because they couldn’t really say what they wanted to say.

Why did you choose this particular poetry collection for our selection today?

Because for me, she epitomises this modern Lithuanian poet. There’s an international flavour to her poetry. She’s a new kind of poet—not someone merely writing poetry without being involved in the discussion that society is having. She’s very much an activist, organising events, able to pull people together to do things. That actually comes out in her poetry, too. She’s someone who constantly wants to push the borders of what poetry is, at least that’s how I see her work.

I felt that it was important to also introduce her to a broader public. When people are making lists, they often forget the poetry, mostly focus on fiction. That was also why I chose a couple of collections of poetry. I want people to be aware of the fact that this work is out there. She has a very contemporary, very situated voice. She’s very implicated in European society today. Hers is not a voice rooted in a specific Lithuanian context necessarily.

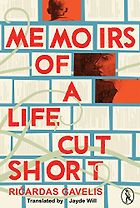

Let’s speak about Ričardas Gavelis. Here’s a writer who’s work is also contextual. The book that you chose is very much a product of its time, the height of the activity of Sajudis, the Lithuanian Reform Movement, which eventually was instrumental in reestablishing Lithuania’s statehood. Along with the other independence movements in the Baltics, it really paved the way for the breakup of the Soviet Union.

We’ve considered a number of young voices. Gavelis you could almost describe as more established in the sense that out of all the writers I mentioned (or am planning on mentioning) he had the longest writing career. It started during the Soviet period. He was a dissident in the Soviet regime, but he was very much at the forefront of the independence movement.

He was one of the harshest, most outspoken critics in Lithuanian literature of the prior regime. You could describe him as a chronicler of Vilnius and the early independent republic. He talks about the emergence of new structures of power, of authority. In the work that I chose, Memoirs of a Life Cut Short, he’s talking about self-awareness. Self-awareness of an individual, of a nation, what it means to be Lithuanian, what it means for a country to be sovereign.

I thought the format of the book was absolutely thrilling. A series of letters between two biographically real but imagined interlocutors. And then a number of other public figures, as well, including Franz Kafka, Albert Camus. I suppose for somebody who is approaching Lithuanian literature for the first time, a work like this could help them to place it in the wider European dialogue with some of the greats of European literature. Would that be fair?

First and foremost, it talks about Lithuanians. For me, this is still the most important post-1989 Lithuanian novel that has been published. It really explains this person who grew up purely in the Soviet era, why they became what they became, and the inner workings of their minds.

“For me, this is still the most important post-1989 Lithuanian novel that has been published”

When I was living in Lithuania, I often had the impression that people really didn’t want to talk about the past, at least the most recent past. I came up with various theories as to why, and when I read this book it all made so much sense. So much fell into place for me about Lithuanian mentality. Gavelis was a merciless critic of Lithuanian society. For him to channel his critique through these letters as if talking with people like Camus and Stalin is an ingenious way of talking about Lithuania in juxtaposition with other points of view, by and large European, which inform or influence Lithuanian culture.

Lastly, let’s turn to Estonia. You chose a poetry collection by Estonian poet Kätlin Kaldmaa called One is None. I applaud you for having chosen two poetry collections.

It was translated by noted translator Miriam McIlfatrick-Ksenofontov and published under the Periscope imprint of A Midsummer Night’s Press. They’re doing some really great stuff with getting poets, especially women, into the public, which is something really commendable.

Her book talks about love and about the geography of where you find love. And not only love, but also the despair that she sees around the world. I don’t even know if I could say it’s a typical example of Estonian poetry, because it’s so introspective. Landscapes feature prominently, but they’re not physical landscapes—they’re the emotional landscapes of people.

I’m really happy that this came out in English. Although she has published several books, I think this is really the genesis of her work. There’s something very representative of all of the things that she’s done. She’s also written children’s books, she’s written a novel. I think she’s a very good representative of Estonian poetry out there. Over the last few years, there have been a number of poetry collections by Estonian poets published, but hers is a standout. It’s also a very short book, only 44 pages.

Are Estonians particularly keen on poetry in your experience?

I would say so. If you look at any top 10 bestseller list of various book chains, you’re always going to see a poetry collection or two. This is almost unheard of in any other country. I think Estonians do a really good job of having a vibrant literary scene. There’s always talk of culture, literary events where poetry always features poetry. The HeadRead Festival in Tallinn, an annual literary event, gets big names but Estonians are an integral part of the programme. You have the Prima Vista Festival which is held in the university town of Tartu in Southern Estonia. There’s always some sort of poetry component to these gatherings, and they have become extremely popular.

I have to say, just knowing how complex Lithuanian grammar is, Lithuanian alone, much less Latvian and Estonian grammar. Hats off to you, for being able to navigate these three very different country’s literary traditions. It’s great to draw attention to the numerous translations in English. Maybe more than ever before. I hope people come up with their own Five Books lists!

Recently in the Latvian media we’ve seen lists like the “Top 10 Best Collections of Poetry,” the “Top 10 Most Scandalous Books in Latvian Literature.” You don’t have to agree with but it gets the conversation going.

Absolutely.

Articles, monographs, anthologies all really help to shed some light on things that are worth reading or re-reading. It would be great to see more of these sorts of things in the future because I think it can only help to get the word out there.

Interview by Romas Viesulas

December 30, 2018. Updated: August 10, 2025

Five Books aims to keep its book recommendations and interviews up to date. If you are the interviewee and would like to update your choice of books (or even just what you say about them) please email us at [email protected]