How did you get interested in philosophy and sport? It’s not a mainstream topic in philosophy, and you’re better known as a philosopher of mind and of science.

I’m glad you asked about philosophy and sport, rather than philosophy of sport, because even though I’ve started working in this area quite a lot, I don’t really think of myself as a philosopher of sport. I got interested in this by accident. I’ve been a philosopher all my working life, and I’ve also always been a terribly keen amateur sportsman. Since I left school I’ve played, in competitive organised contexts—cricket, rugby, soccer, field hockey, tennis, golf, sailing and squash—without very much success in any of them. But it’s occupied a great deal of my life, not to mention watching on television an awful lot. Somehow I’d never put the two things together. But then I was asked to give a talk in a series running up to the Olympics, ‘Philosophy of Sport’, organised by the Royal Institute of Philosophy, and I started thinking about the nature and value of sport. I wasn’t getting anywhere, and then I thought, no, I’m just going to write about something that interests me: I don’t care if it’s really philosophy of sport. I wrote about fast sporting skills and concentration, especially in the context of cricket, and I had great fun. I told lots of sporting anecdotes, but I actually developed a philosophical thesis that I hadn’t had before. And then I realised that there were quite a few philosophical topics that were illuminated by sporting contexts, that somehow sport highlighted philosophical issues in a way that they weren’t always highlighted in everyday life. So I’ve been working in this area a lot recently, and I’ve come up with many ideas of that kind. My interest is in sport being used to illustrate philosophical issues of a general kind, and also in philosophical ideas being used to highlight certain features of sport that people mightn’t have thought about.

Could you give an example of the kind of philosophical problem that’s illuminated by something that occurs in sport?

Let me just take something that won’t come up in any of the books we are going to discuss, which is ideas of altruism and team reasoning, the tendency of humans to co-operate. This is something that’s of great interest to philosophers, evolutionary biologists, and economists. They develop all kinds of models, but you can see the issues that they’re talking about very graphically illustrated in any number of sports. One that grabbed my attention was road cycle-racing, where you will see individuals from different teams, with no common interest, co-operating for nine-tenths of the race, going out in front, taking turns being in front. Why are they helping each other? What’s going on here? If you think about it, it casts some of the philosophical and analytic issues in a very helpful light.

And you wrote about that on a weblog. Why did you choose that way of communicating your ideas?

I didn’t really think of this as a way of communicating ideas I already had. It was just that I discovered all these really interesting topics. I’m a philosopher, I’ve got a philosophical turn of mind, and I spend a lot of time playing and watching games. So I’m naturally inclined to start thinking in philosophical ways about this area that many other people are interested in, and probably haven’t thought about from quite that perspective. So I thought I had something interesting to say, and I just found myself putting out these ideas. I didn’t write only about altruism and co-operation, but also about fast-sporting skills, fandom, identity, nationality, heredity, the economics of sport and so on. Why a weblog? I didn’t want to be particularly academic. I don’t want to say that I didn’t want to be careful and precise—I did want to be careful and precise—but I found it quite liberating to be writing outside an academic context. I found I could explore and put forward ideas without the constraints of all the academic paraphernalia. That was fun, and I thought it was suited to this topic. I wanted to reach an audience who would probably be impatient with careful philosophical argument going on, paragraph after paragraph. I wanted to get the argument across but illustrate it with sporting stories, sporting references, and this made it a nice way to write. I’m going to write a book now drawing on that material: I’m stopping the weblog so I can write the book, and I hope to do the same kind of thing with the book.

Now, let’s go to the first of your book choices, Bernard Suits’s The Grasshopper which, for a long time, was a very-little-known classic, and now it’s probably just a little-known classic.

My first choice is a book about the nature and value of sport. I wanted to look at this via Suits because his is probably the best-known full-length work in this area. It’s a wonderfully engaging, eccentric, ingenious book, which has a terrific idea in it, but I think it’s completely wrongheaded about the nature and value of sport. So I’ll start by explaining the good idea, and then explain why I think it’s not as helpful for understanding sport as many of its enthusiasts suggest. The book is a quasi-Socratic dialogue with the grasshopper as the main character, and the grasshopper’s idea is that the highest virtue is playing, that he is going to spend all his time playing, doesn’t care if he dies, and the overall argument of the book is that in utopia, where humans have all their material needs satisfied at the push of a button, what we would do would be play games, and therefore playing games is the ideal of human activity. Freed from all the necessities of having to do things we don’t want to do in order to get the material means of life, we’d do nothing but play games. That’s the main thesis.

And at the heart of this, there is this apparent critique of Wittgenstein’s notion that you can’t define what a game is, give its essence, because ‘game’ is a family resemblance term. The alleged impossibility of defining the concept of a game was the main example Wittgenstein used to illustrate his notion of a family resemblance term.

Suits does two things. He defines ‘games’ and, following on from that, he argues that the playing of games is the highest form of human activity. But the first part of the book, as you say, is a head-on attempt to meet Wittgenstein’s challenge. Wittgenstein said the concept of a ‘game’ was indefinable: you can’t give a set of necessary and sufficient conditions that pick out all and only games, because games have nothing in common. Rather, they have a set of overlapping similarities, like the resembling faces within someone’s family. Suits comes up with this very neat definition of ‘game’ to refute this. I won’t give you the long version: in the shorter version, he explains that a game is any voluntary attempt to overcome unnecessary obstacles. So, his idea is that in a game there’s some aimed at end point, or target. With Snakes and Ladders it’s getting your counter onto the final ‘100’ square; in golf, it’s getting this little white ball into a hole; in a 100-metre sprint, it’s breasting the tape ahead of the others. So there’s some target of the activity, and then, Suits says, what picks these activities out as games is that we put arbitrary restrictions on how to achieve that target: you have to do it by rolling a dice and going up the ladders and down the snakes; or you have to do it using golf clubs of a certain specification, and you can’t pick the ball up; and you have to get across the tape first by running, and not by shooting the others, or by getting on a motorbike or anything like that. So there are arbitrary restrictions on how you’re allowed to achieve the end, and Suits says whenever you’ve got a game, you’ve got that setup, and anything that fits that setup counts as a game. With a kind of awkwardness that I’ll come back to in a bit, he then spends the rest of the book with all kinds of strange fables and odd characters, defending the thesis that he’s produced a very neat set of necessary and sufficient conditions for something being a game, and I think he’s pretty close to achieving that. He does a very good job of showing that not just standard games, but games like hide-and-seek, and role-playing games, and so on, all fit his definition, and that part is pretty convincing.

But you’re sceptical about it providing an insight into sport, rather than the general category of the ‘game’?

I have two big doubts about what then comes in Suits. One is whether his definition of a ‘game’ is much help at giving us a definition of sport; and the other is whether his definition of a game gives us any idea about what we find valuable in games. Focusing on the second of these doubts first: Suits’s idea seems to be that once we’re freed from the necessities of life, we’ll set ourselves challenges and then find value in the overcoming of these challenges, and if we put to one side the practical needs of life, the only challenges that will be worthwhile will be the ones we set ourselves in the way that we set ourselves challenges in games. I think that’s a completely hopeless idea. Suits’s idea seems to be this: take something which is completely pointless, make it difficult, and then it’s important to overcome the difficulties. I’m inclined to think that if something isn’t worth doing, it’s not worth doing even when you make it difficult, and I just don’t see any plausibility in Suits’s account of the value of games.

Why would somebody have a hopping race then, because most people have got two legs, and can run. Why would you have a hopping race ever?

A hopping race is an interesting case. Let me say what I think is of value in sport, and that will then put Suits’s idea of games in context. I don’t know anything about Suits personally, but reading the book, you certainly get an impression of somebody who’s never hit a sweet cover drive, or hit a backhand crosscourt, or driven a golf ball 250 yards. There’s no sense in the book anywhere of the pride, pleasure, enjoyment, and value, that people get out of the exercise of physical skills. My view is that what’s valuable about sports is nothing to do with games, and nothing to do with overcoming arbitrary obstacles: it’s the enjoyment and value that people get out of the exercise of physical skills. You can get a pretty good definition of ‘sport’ by saying it’s any activity, the primary purpose of which is to allow the exercise of physical skills. The nature of sport is the exercise of physical skills, and the value of sport is just the value that human beings find in that. I think this goes very deep in human nature – developing, exercising, extending physical skills, and displaying them.

“Wittgenstein said the concept of a ‘game’ was indefinable.”

Not all sports are games, and not all games are sports. Suits seems to think you can just characterise sports as that sub-class of games that involves physical activity. In fact, when you think of sport in the way I’ve just defined it, then it becomes clear that there are quite a lot of sports that really aren’t games at all. While I believe Suits gives a good analysis of games, in the book he tries to extend his analysis to cover sports like rowing, sprinting, boxing, and windsurfing, which just aren’t games at all. They’re sports in my sense, they’re activities that allow the exercise of physical skills. Suits should never have started trying to make them games. They don’t fit his definition very well. He should have recognised that some sports fall outside of his definition of games, but then he would have had to acknowledge that sports have a value that doesn’t consist in their being games. Some sports are games—tennis is a game, cricket is a game—and the skills that you exercise in the context of those games wouldn’t really exist outside the games: there wouldn’t be any crosscourt backhands if there wasn’t tennis. But what makes hitting a crosscourt backhand valuable is that it’s a physical skill that you can take pride in, and not that it’s part of a game, that’s incidental to what makes it valuable. If you look at the overall range of games, the thing I’ve just said about games and sports applies to other games as well: many games don’t involve physical skills, but involve intellectual skills—think of bridge, chess, and so on—and people enjoy and find value in those activities not because they involve overcoming arbitrary obstacles, but because they allow the exercise of intellectual skills, which are things to take pride in, things that are important. Then there are games that are valuable because they engender a certain kind of excitement, like gambling games. That’s what makes them valuable, again, not because they are the arbitrary overcoming of obstacles, but because they give rise to something which independently has value, namely the excitement, absorption, and so on. I want to say about games in general that the games that have value, if they have value, have value for some other reason than the one that Suits focuses on.

In a way, you’re demonstrating why this book is a book worth reading because he made you think. It sounds as if many of your ideas have come out in opposition to Suits?

Absolutely. I’ve been going on about how wrong Suits is, but The Grasshopper is still a terrific book. It’s very eccentric, it digresses with strange characters and fantasies involving the behaviour of his characters, going on for pages and pages. It’s all very engaging. Is the book itself a game? In the course of the book, he raises all kinds of questions, including that one, and gives them mostly very good answers. As I said, the book’s absolutely right about games, it seems to me that it knocks Wittgenstein’s negative view on the head. If somebody is interested in trying to understand games, this is exactly the place to start. It also focuses on the question of why games are valuable. I think Suits gives a wrong answer, but he’s crucial for raising the question, and making us focus on it.

Now, your second book is written by somebody who did graduate work in philosophy at Harvard but, unlike many philosophers, moved from very general and abstract thinking to the particular, and became a brilliant essayist and successful novelist.

This is David Foster Wallace’s Both Flesh and Not, a collection of his essays, the longest and lead essay of which is an essay on Roger Federer called ‘Federer Both Flesh and Not’, that was originally a New York Times’ piece about how watching Federer was like a religious experience. Foster Wallace sadly committed suicide. He was a terrific novelist, and was himself a very interesting character. Apart from his 1000-page novel, Infinite Jest, he wrote a book about the mathematics of infinity, Everything and More, which is maybe a failed attempt, but a very interesting failed attempt, involving a lot of detailed mathematics. On top of that, he had been a competitive junior tennis player at state level, and spent many of his teenage years in tennis camps. So he writes about Federer with the kind of knowledge that a competitor himself would have. One of the things in the essay is an appreciation of the value and beauty of sport. He says that the aim of sport is not to be beautiful, to be aesthetic, but inevitably this is something that comes out. There’s a nice phrase he uses, that ‘the beauty of sport is to do really with human beings’ reconciliation with the fact of having a body’ [p.8]. I said, in talking about Suits, that the value of sport lies in the enjoyment, the value of exercising physical skills, and that this goes very deep in human nature. Maybe not everybody has this facet to their lives, but one of the things that humans do is perfect skills to an absurd and unnatural degree, and not just in sport—if you think of musicians, and typists (when we used to have typists), people can learn to do amazing things with their bodies, and people start honing and developing these skills as an end in itself. It’s a very natural thing for humans to do.

Part of the Federer essay is about the beauty engendered by extreme levels of physical skill, but Foster Wallace also focuses on the mechanics of it. He has this insider’s appreciation of how very difficult this is. What you’re watching Federer and Nadal doing is at an incredibly high level, something that you only truly appreciate when you’re at the tennis court, rather than watching on television. When you watch it on television you have very little sense of how hard they’re hitting the ball, and how fast it’s coming. He points out—and this is something that interests me a lot, and was the subject of my first writing about sport—that it is all effectively unconscious when somebody hits a ball very precisely when they’ve only got 400 milliseconds, less than half a second, the time it takes you to blink twice very quickly, between the ball leaving the other opponent’s racket and getting to you. There’s no time for any conscious thought. It really is all reflexes. At the same time, he points out, Federer is a tactician—he describes one point against Nadal where Federer moves him around and then slows him down so as to open up the court for a crosscourt, and then hits a crosscourt, and it’s very intellectual—and so there’s a real puzzle there about how deliberate, conscious thought can interact with these split-second reflexes. To be honest, Wallace doesn’t answer this conundrum, but he raises it in a very acute form. He also talks about something else that’s very interesting about high level fast-sporting skills, he talks about how much time Federer seems to have. To Federer is seems as if the ball is coming slowly, he seems to have ample time to be graceful, whereas other players are just rushed.

Get the weekly Five Books newsletter

Something Foster Wallace doesn’t talk about, something that sports science is now illuminating, is the extent to which players know where the ball is coming long before the opponent has hit it, they draw all kinds of inferences from the posture, from the angle of the opponent’s wrist, and so on, and so they’re already moving to where the ball is going to go, and they already know what kind of shot it is going to be, quite a while before it is hit. There’s a nice example of this with Desmond Douglas, who was the top British table tennis player for a long time: he was famed for having fast reactions, and could stand much closer to the table than other players, and take the ball earlier. But when sports scientists tested him, his reactions weren’t that exceptional, and it turned out his ability wasn’t based on fast eye-hand co-ordination at all: it was based purely on the ability, from his experience, to read from the posture, and other cues from his opponent, where the ball was going to be coming before it was hit.

What I like about the Foster Wallace essay is that he gets underneath the surface of sport, he sees how amazing and beautiful it is that athletes can do things which most spectators don’t think much about, and take for granted. He has a philosopher’s curiosity about how such things are possible. They’re the kinds of things I’ve been writing about in my blog and want to go into more when I write my sports book.

The third book that you’ve chosen is Moneyball, which is a very different kind of book: it’s all about applying rigorous statistical understanding to players’ ability to play baseball.

Yes, this is a book by Michael Lewis. I’m a great admirer of Michael Lewis. He’s by far the most accomplished, most entertaining, most informative non-fiction writer around at the moment, and I’m slightly surprised he’s not better known in Britain. I wanted to include this book because it seems to me a parable of the disinclination of people to base their practices on evidence, and for evidence-based policy in general. The book focuses on Billy Beane, an interesting figure who is the general manager of the Oakland Athletics. The Athletics punched way above their weight in the time leading up to the writing of the book, and Lewis got interested. How did they manage to hold their own when they had a third of the money to spend that the Yankees and the other big teams had? As he tells the story, Beane was the first Major League Baseball figure to pay any attention to something that had been going on for about 40 years before this, which was geeks analysing baseball statistics and figuring out that the supposedly tried and tested strategies of the managers, who were mostly old baseball players, were completely misguided, and that you could clean up just by making a few simple strategic changes. This whole movement is known as ‘sabermetrics’ (from the acronym SABR from the Society of American Baseball Records) and was started by an eccentric statistical analyst and writer, Bill James. He got the movement going in the late 1970s, though it goes back even earlier.

I don’t know how many people have read Philip Roth’s book, The Great American Novel. It’s difficult for English people to read because it’s a fantasy, picaresque, non-realistic, extravaganza about an imaginary baseball team in the 1940s, and it’s Roth at his most playful and untrammelled. It’s a lot of fun. One of the baseball teams in that book has an owner whose son Isaac Ellis is a self-styled ‘17 year-old Jewish genius’, and he goes to all the players and the manager of his father’s baseball team, and says, ‘Look, you’re doing it all wrong, you really shouldn’t be making sacrifice bunts, that’s costing us 70 runs a year, and all this stealing bases, it’s even worse,’ and he demonstrates it all with graphs, and they all say, ‘You’re nuts, please go away.’ This book was written in 1973, and Roth credits Earnshaw Cook, who’d written a book developing these ideas back in the 1960s, so the facts were out there for 40 years before anybody in baseball took any notice. This is odd because it’s a competitive sport, you want to win, and there are huge amounts of money involved. Nowadays the players are paid ten million dollars a year salary, and even back in the 1970s, ‘80s, and ‘90s, there were significant amounts of money involved. Yet nobody ever bothered to do the sums to figure out whether what they were doing was sensible.

Wasn’t that because, as in many sports, and in other aspects of life, people are seduced by appearances? Some people look like sports people, but it doesn’t mean they can perform better than people who are slightly ungainly. In soccer, we’ve had Peter Crouch who came through. He didn’t look like a footballer because he’s six foot eight and very skinny, and a lot of people were very prejudiced against him being an effective striker, but if you analyse the statistics, he’s a match-winner.

That’s part of it. Billy Beane, the central figure, was himself a great young baseball hopeful, he looked completely wonderful, and he played in Major Leagues on and off for a few years, but he never batted well enough for the level at which we was playing. That sort of weakness does get found out, it’s like a plausible-looking striker who never scores any goals. You’d see at the end of the season, he’d only got five goals, not 20. Billy Beane was averaging in the low 200s as a batter, and that’s not good enough. So it’s not as if people who look good but don’t perform don’t get found out: it’s more subtle. Baseball batting averages are the traditional way of assessing the worth of a batsman. But the statisticians showed that batting averages are a terribly crude tool, and RBI (runs batted in), another statistic they use all the time, is another terribly crude tool: they don’t measure what you’re really interested in, they don’t measure how much the batters are contributing to the success of the team. If you’re no good, you’ll be found out even by these crude measures, but if you really want to work out which are the best players to spend your money on, which tactics you should be encouraging, then you need a very careful statistical analysis, and nowadays, all the baseball teams do use it. The shocking thing is that the data and information were available for decades, and somehow they just all ‘knew better’. They knew better in their guts that the right way to play was the way they’d always played, and it makes one think that, well, baseball managers, they are a kind of in-between case: they’re baseball managers, they spend all their lives in baseball, they have all these very strong traditions and ideas, so that’s going to count against them innovating. On the other hand, they are in a very competitive environment involving lots of money, and you think that analysts would come in and tell them what to do, but they didn’t. The analogy that one immediately wants to draw, and of course it’s worrying, is politics in general. There are politicians and people who vote for them who think that they know in their guts what’s right about immigration, drug policy, prison policy, economics in general, and they will vote and the politicians will follow them just on these gut reactions; even when there’s plenty of statistical evidence around showing that the policies everybody favours are not going to produce the effects they want.

This evidence-based thinking, and thinking which avoids the evidence, or doesn’t think to look for the evidence, is prevalent across a wide range of areas, including philosophy. Appointments of philosophers are often made in academic departments on non-statistical bases, and nobody is trying to work out the trajectory of somebody on the basis of past performance through complex analysis. Ultimately they look at the different features and get some kind of rough feeling, ‘Is this the right kind of person?’ And they usually end up with a male philosopher who is a bit like themselves, as it happens. This book is really fascinating because of the light it casts on a particular sport, but it seems to have much broader implications about how sporting performance and other aspects of life could be improved by rigorous application of scientific principles.

I think the lesson’s probably been learnt within sport. Famously in baseball, the Boston Red Sox, who never won the World Series since they sold Babe Ruth back in 1920, tried to hire Billy Beane, and he wouldn’t go. Then they hired one of his disciples and they won the World Series a couple of years later. So baseball has learnt its lesson. My understanding is that soccer now uses very similar techniques. When there are huge amounts of money involved and plenty of people coming out of business schools all ready to help—sports enthusiasts themselves—it would be surprising if one didn’t see this kind of analysis informing decisions in all kinds of sports; it’s just a pity it isn’t used more generally outside sport.

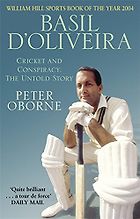

Let’s move from empirical, statistics-based analysis of sport, to a personal story which had a really serious political background to it, and implications for many people. Your fourth book is a biography of the cricketer Basil D’Oliveira.

It’s partly biography, but it also focuses, in the second half of the book, on the wider issues in, and background to, the D’Oliveira affair in 1968. I wanted to include something about race and sport. I thought of Beyond a Boundary by C. L. R. James, a great West Indian writer and activist. It’s a memoir, it’s focused a lot on his life in the West Indies, in Trinidad, in the 1920s, and then going to Lancashire with Learie Constantine in the early 1930s. That’s very interesting and illuminating about overturning the white domination of cricket in the West Indies. But it’s all so long ago, and it’s a bit quaint and almost Edwardian, the colonies and imitation-public schools. I decided to go for D’Oliveira instead because that’s more recent, it’s certainly in my memory. It’s surprising to look back now and see how much racism there was in sport. Did you know that New Zealand sent a segregated rugby team to South Africa in 1960? In 1960, New Zealanders were still prepared to leave the Maoris out of their rugby team in order to play rugby against South Africa. It’s quite hard to believe.

“The nature of sport is the exercise of physical skills, and the value of sport is just the value that human beings find in that.”

D’Oliveira was a so-called ‘coloured’ South African and a wonderful cricketer. He was well-known within black South Africa, a few people had heard of him outside, and he was desperate to develop his sporting career. There was no way he could do this in South Africa: he was captain of the non-white South African team, but they never had anybody to play against. He wrote to the cricket writer and broadcaster John Arlott asking whether there was any way that he could come and play cricket in England, and he left South Africa—there’s always uncertainty about his age, he must have been about 30—and within six or seven years, he was playing for England. It’s a wonderful fairy story. And then the question arose, was he going to play for England on the tour to South Africa? The second half of the book is all about the shenanigans involved in the run up to the selection of the team for the tour, and Peter Oborne, the author of the book, has done a proper historical job. He’s gone and looked in the archives—there are all kinds of records now that have come out, all kinds of minutes of meetings and so on. He makes it clear that the South African government were determined that D’Oliveira wasn’t going to come, but they couldn’t say so publicly. They didn’t want to announce that they weren’t going to have a team with him in, lest he wasn’t selected, in which case they would have blotted their copybook unnecessarily. But they wanted to tell the MCC surreptitiously that they would veto the tour if D’Oliveira was selected, in order to encourage them not to select him. They played a very complicated game, very successfully. What happened was this: D’Oliveira wasn’t in the England team against the Australians for most of the 1968 summer, he’d lost form a bit, he wasn’t first choice. It’s not clear whether at that stage he wasn’t getting in the team because there was a faction that was trying to stop him kyboshing the South African tour … but anyway, through a sequence of circumstances, he got into the team for the final test—and he seized his chance and scored a hugely important and wonderful century, 158. And that was that, we all thought. And then the MCC selection committee, with a number of MCC luminaries in attendance, managed not to pick him—not to pick someone who’s just scored 158 in the last test of the summer season makes no sense at all, but somehow they managed it. Another important thing about the story is that D’Oliveira, who was a completely unassuming non-political, rather quiet fellow, turned out to be a complete hero through all of this. South Africans tried to buy him off that summer. They offered him a coaching contract—in today’s money worth of the order of £150,000—and he said ‘No, I want to go and play cricket in South Africa.’ So, the moral of the book is that race was a huge factor in British and Commonwealth sport until very recently.

It should also remind us how hopeless the England cricket authorities are at managing things: that’s a moral that’s still with us. About racism in sport more generally, it’s a complicated story isn’t it? I think that racism has largely disappeared from British sport, and maybe that’s to do with the fact that Britain is pretty successful as a multicultural society. It’s quite recent, something that comes up in the next book that we’re going to talk about. There were racists shouting at black football players in Britain through the 1980s, into the ‘90s, and it’s now disappeared. One would like to think it’s disappeared, both inside and outside sport, but it’s not clear that’s the case across Europe, thinking about soccer. One would like to think it was the case in America: North American sports are fully integrated, and I know of no suggestion that there’s any remaining discrimination within professional sport. But, of course, there certainly are racial tensions outside sport in North America, in a way that I think is not so much so in this country. It’s not clear how far that makes a difference to what’s going on in sport in North America.

Your fifth and final book, Nick Hornby’s Fever Pitch, strikes me as one of the first books to take seriously the fan’s role in sport.

Yes, so far we haven’t said very much about the fan’s role. Of course, when it comes to professional sport, the whole thing rests on the fans, and people who pay to go and watch. I picked this book, not just because it’s a terrific book—it’s largely a personal memoir, with the fate of the Arsenal football team through the 1970s and ‘80s as a kind of backbone upon which to hang Hornby’s story—but also because it highlights the peculiar nature, the kind of obsessive but also accidental nature, of sporting fandom. Sporting fandom is very interesting philosophically: it’s a case of partiality, partisanship, valuing something when you can see that what you value isn’t going to be valued by other people. Some philosophers have difficulty with the idea that something can be genuinely valuable for one person, when it wouldn’t be for another person, even another similarly placed person—somehow what’s valuable for you is partly down to you, to your committing to something, your deciding you’re going to be a certain kind of person. There’s a natural philosophical tendency to want to try and explain away the possibility of such partiality. But if you think about football fandom, or fandom for any kind of club, it’s difficult to deny that, for many people, some of the most important aspects of their lives are tied up with their partisan enthusiasms. Hornby explains how it was almost an accident he became an Arsenal fan. He was living in Maidenhead, and his parents were separated and his father wanted to take him somewhere on Saturdays; he could have easily gone to Chelsea or Tottenham, but he went to Arsenal. At his first game he was hooked, he had an affiliation, he wanted to be part of this thing.

Get the weekly Five Books newsletter

One of the interesting things about sporting fandom is that it’s valuable, it’s important for you, you don’t think there’s anything irrational on your part, it is genuinely important for you that Arsenal win. But, at the same time, you can see that it’s quite symmetrical: the Spurs fans are just as rational, serious, proper people as you are, and yet they feel just the same way about Spurs that you do about Arsenal. My view is that the attempt to remove partiality, partisanship, agent-relative values from normative philosophical theory is misguided: life would be much thinner, unrecognisable, if people didn’t commit themselves to certain values, enthusiasms, decisions about what’s important, even when there’s no imperative for somebody similarly placed to take the same view. Life wouldn’t be the same if we didn’t have our personal commitments. But, at the same time, sport makes it clear that you shouldn’t want to impose your personal commitments on other people. Some idiotic football fans think it’s a consequence of their supporting Arsenal that they should despise, disapprove, look down on Tottenham fans, that such people are somehow morally inferior and misguided. I think that’s a small, and rather stupid, minority. Most football fans can see that these other people have just as important a claim on all of the good things in life as they do. That too could have more general moral significance—we shouldn’t try and wipe out partisan commitments to your school, your village, your family, your country, but we shouldn’t let that cloud our minds to the fact that we have no greater claim on important things in life than people on the other side.

In Fever Pitch, there’s a sense that joy and suffering, the great emotional surges, and, at least in his early life, the whole of Hornby’s life revolves around the fate of his team. It requires him to make that kind of commitment to achieve the emotional sense of being alive: he couldn’t have achieved those levels of intensity without the commitment. The so-called neutral viewer of a match who enjoys it on aesthetic grounds, and admires skill, couldn’t possibly go through the same range of emotions as him.

Yes, but is he lucky or not in that respect? He’s an extreme case, and as he says in the book at various points, he keeps getting introduced to people as, ‘here’s a fellow Arsenal fan.’ But most of them turn out not to be real fans: they just look at the score on Sunday mornings. That’s not what he means by being a fan. It’s pretty clear from the book that the extreme commitment and dependence on Arsenal is making up for other things in his life. Hornby’s commitment to Arsenal has an emotional intensity that isn’t shared by many other more part-time fans. Stephen Mumford, a philosopher at Nottingham, has written a book which is a plea for impartial sports appreciation. He thinks that the fan is being blinded to the pleasures, the aesthetic pleasures, the pleasures of appreciating tactics, the pleasures that are open to a non-fan, somebody who watches the game just to appreciate the finer points of the play, and doesn’t really care who wins. I’m not sure I agree. As I said, I think life would be thinner, much thinner, life would be pretty much unrecognisable if we didn’t find ourselves siding with groups to which we have found an affinity. Sometimes we don’t choose them, our families, our schools, our countries, but sometimes we do—our fellow hobbyists, people who like Mississippi Blues, people who like certain kinds of philosophy—and we root for our team. To feel that life would be better if we didn’t become partisan and tried to see everything from an unengaged point of view, is the wrong way to live. At the same time, we shouldn’t feel that our commitments should automatically have priority over other people’s commitments.

Five Books aims to keep its book recommendations and interviews up to date. If you are the interviewee and would like to update your choice of books (or even just what you say about them) please email us at [email protected]

Five Books interviews are expensive to produce. If you've enjoyed this interview, please support us by donating a small amount.