If it’s all right, I’d like to start with something personal. Your grandmother was murdered when you were 15 years old; I think it was that event that made you interested in studying mental health. Is that right?

Yes. She was beaten to death; I suppose I was at that time of life when you think that everything is possible and that you can change the world, and to have that kind of experience probably was a bit of a crashing, sobering realisation that maybe the world wasn’t as fantastic as I thought.

She and my father had a complicated relationship anyway, so it was quite an event for lots of reasons. I didn’t realise at the time, but I think it made me probably more fascinated with why people do what they do, particularly when it comes to such unbelievably destructive events, like killing somebody.

And was the person who killed your grandmother mentally ill?

She was eight months pregnant and a heroin user. When I qualified as a clinical psychologist many years later, the first job I had was a split post between HIV/Aids and drug dependency, and, in the drug dependency part of it, one of the first things I did was set up a group for women who were pregnant and using. It wasn’t until I told one of my close friends from childhood that I realised the link. She was the one who pointed it out. She said, ‘I’m no therapist but, hello?’ And honestly, it had been a completely unconscious thing. And I am not a major psycho freak head, I am much more a practical solutions kind of girl and therapist, but when I thought about what my friend said, I saw it made sense.

And that was cathartic.

Yes.

Well, let’s talk about your first book: Dibs in Search of Self, by Virginia Axline.

Virginia Axline is a family therapist, and I like this book because it really resonates in terms of why I do what I do and, particularly, why I am passionate about child and adolescent mental health. The book is all about child therapy and a boy called Dibs who wouldn’t talk and wouldn’t play. He has lots of difficulties and issues, and I think he represents a lot of children with mental health problems who are easily misunderstood. We get very anxious about mental health – and when it comes to children we get deeply, deeply anxious about it.

What this book does is to beautifully and sensitively describe how we can understand such a bizarre presentation, and, by understanding it, how we can unlock this little person and enable him to be understood and be the best little person he can be. I think it is a very empowering and kind book. It’s very moving because it is hopeful; it presents a child who has clearly got a huge neuro-developmental problem, and shows that this is actually a child who also has a huge amount of really incredible stuff about him. If you just take the time to look, you can understand so much. And I don’t think we do that with children. We are a real child-hating society. I don’t think we really think enough about what children do and why they do it. We make too many judgments and pronouncements.

We have a whole culture of young people who are completely disenfranchised. We don’t value youth. We have young people who are doing some pretty out-there things, which I think is a way of demonstrating their concerns and their distress and their issues, and I think we are very good at labelling.

Rather than helping them.

Yes. And, as someone who has worked in the NHS, I think the amount of investment in child mental health issues is pants. We are the Cinderella service. I am a chancellor of a university, and we are all really grappling with the issue of fees, and it just feels horrendous to me when you think about what we are doing to kids today. My generation and my parent’s generation are culpable in the sense that we created all this debt which we are now saddling on our young people. What this book does is to celebrate children and the complexity of children. It reminds us that we have to really listen and think about why a child is telling us something. The behaviour of children and young people is fundamental to a well-functioning society, because they can tell us what is going on more honestly than we tell ourselves.

Your next choice is The Unquiet Mind: A Memoir of Moods and Madness, by Kay Redfield Jamison.

This is a divine book. A patient of mine who suffers with a bipolar illness, an absolutely inspiring young genius, recommended it to me. So I read it, and then we discussed it in a lot of our sessions together.

It’s written by a woman who is a clinical psychologist but also a professor of psychiatry in the States. She is an incredibly talented woman. Her expertise is bipolar illness – but also, she has it herself. To read a book written by someone who has a brilliant and comprehensive theoretical understanding of a very complicated mental health issue, and who also has an understanding of it from a personal point of view, is truly humbling.

The book envisions a world where we can have people with major mental health issues being ‘out there’ about it, and being respected and accepted for it. And I think the author is very brave. She has written a very exposing book, in which she has really described the roller coaster ride that she has had with her own mental health issues, and how it has affected her relationships and her life and the choices she has made. She also explains things in a way that you know comes from a very deep level of understanding.

And, having been through all that, she still thinks there is a way to integrate people with mental health issues into society?

Completely, and she is that example. I just wish she didn’t live in the States. I would love to go and have dinner with her!

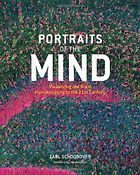

What about Portraits of the Mind, by Carl Schoonover?

This is a picture storybook about the brain, which sounds really mad. But both my kids have looked at it with me. My son is nearly 13, and my daughter is 15, and they really liked it. It is such an engaging book because the brain is so fascinating – but people are quite often scared to think about it.

This is basically a history of how we understand the brain. It starts with the early philosophers like Aristotle and so on. It also has just the most beautiful pictures and drawings and diagrams of the early dissections – and then, eventually, we get to the current level of photography in terms of the microscopic detail of neurons and dendrites and synapses and all the amazing things about this amazing part of us. So I think it is brilliant. And if you can’t be bothered to read it all, you can just look at the pictures and read the captions, and you learn so much.

The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat,

by Oliver Sacks, is up next.

This is a bit of an obvious one, but it is such a genius book. It is a seminal book that anyone who wants to work in mental health should read. It is a charming and gentle (and also honest) exposé of what can happen to us when our mental health is compromised for whatever reason. The title is great, and, because the case studies are very bizarre, it does fly right into that stigma which exists around the whole issue of mental health, which is the differentiation between normal and abnormal. (Either you are on one side or the other, and, if you are on the wrong side of normal, then basically, according to society, that is it, pack your bags and leave.) But actually, what the book does is to blur that line – and he talks about some very, what we would call pathological behaviour. But actually, it is completely sane in the context of how it is presenting itself.

For me, the book is a really lovely challenge in the whole debate around normality and abnormality and the constraints we put on our understanding of mental health because we are so label-conscious.

So how do you think we as a society can help people with mental illnesses?

I think it would be helpful if we could accept that mental illness and physical illness all lie on a continuum, and sometimes bits of our physical body don’t work very well, and sometimes bits of our mental body don’t work very well – and that that’s OK, and it’s actually not an indication of failure. If you break your leg, you are not going to suddenly be seen as less successful than you were before you had broken your leg. So why do we have this stigma around mental health?

I have written about my postnatal depression and also how depressed I was when my father died, and I am not concerned that people know that and that I was treated for it. I think people do need to be more open, so that there is less of a stigma attached to this issue. We are scared of people seeing us as somehow not the person they thought we were, as if life is a competition and the only way that you win it is by being completely invincible and robust and never being fragile or vulnerable. That is just ludicrous. That is why I like kids: because they remind us that life really isn’t like that.

Your last choice is No Fear: Growing Up in a Risk Averse Society.

This is written by a friend of mine, Tim Gill. He is a really, really interesting guy, who is a champion of the rights of children’s freedom. I coined the phrase a few years ago that we raise children in captivity. We live in a society where there are fundamentally no free-range children. He writes beautifully about that. It isn’t a huge book, and it’s very easy to read. He just lays out very simply how we are absolutely screwing the development of children, given our complete paranoid fear of the world we live in.

Get the weekly Five Books newsletter

He explains that in terms of the reduction in the freedom for children to play and for them to actually have accidents that are really important for them – because they need to be able to take risks, and for the risks to sometimes lead them to learn some hard lessons. He really makes us look at the way that we are letting children down, thanks to the paranoid way that we live our lives.

Why do you think we have become like that, given that, statistically, life for children now is allegedly no more dangerous than it was for us when we were children?

It’s easy to say, ‘Oh, it’s the media’. I don’t think it is the media’s fault, but I think we live in a fast-moving, multi-platform, multimedia society, where as it happens we are watching it happen. So as the planes go into the Twin Towers, we see it happen. We are living it as well as hearing about it later. We are experiencing the trauma as the trauma happens, and then we internalise that, and suddenly the trauma becomes ours and we suddenly look at those we love most deeply and think, ‘I am not going to let that happen to them. So we will just keep you in your bedrooms until you are 18 and hope for the best!’

What is the best thing we can do for our children?

We can get children to go to school on the bus starting when they are much younger; we can let our kids have more freedom to play outside; we can have communities where cars aren’t allowed on certain streets so children can play out together. We can stop this ridiculous health-and-safety culture where children aren’t allowed to climb trees, or play conkers, or throw snowballs.

Five Books interviews are expensive to produce. If you're enjoying this interview, please support us by donating a small amount.

Instead, everyone sits at home, going on Facebook or playing computer games.

Which is fine in the sense that I look at the way my kids use their computers and social networking and I am jealous. I think about how I used to go off to the local library and get a book out of which someone had ripped the key pages – but now they get all the information they need! So I am a champion of technology, but I do think everything is good only in moderation. The irony is that we live in this risk-averse culture; we are perversely paranoid about our children’s safety, so we keep them indoors, and we then allow them to do their childhood – which is socialising, communicating, playing, etc. – online, and because none of us has had the experience of the online space, we haven’t even prepared them for that. So the real-world risks that we understand, because we faced them as children – we are keeping our own kids away from those, and driving them towards spaces where there are risks as well as opportunities and benefits. And we don’t even talk to them about this.

There are some recent stats which show that three-quarters of all five-year-olds are surfing the net, and often they are doing so unsupervised. Would you take your five-year-old to a huge shopping centre and say, ‘I’ll see you in a couple of hours’, and then go and have a cup of coffee? That is why this book is so good: because it highlights that irony, and the ridiculous way in which we are not letting children be children.

March 17, 2011. Updated: September 22, 2023

Five Books aims to keep its book recommendations and interviews up to date. If you are the interviewee and would like to update your choice of books (or even just what you say about them) please email us at [email protected]