This is the second year that we’ve come together to discuss the National Book Critics’ Circle (NBCC) shortlist of the best new biographies. Have you noticed any trends or themes among the 2020 intake?

There are so many new, diverse voices, and so many interesting approaches. We’ve taken an expansive view of biography as a genre, going beyond the narrative of a single life. While our committee agreed on these five books, so many others could well have been finalists.

There seem to be fewer dutiful biographies of great men revered for their prominence rather than accomplishments. As the great historian and biographer Barbara Tuchman—winner of the Pulitzer Prize for The Guns of August and Stilwell and the American Experience in China: 1911-45—once told me about a presidential candidate: “Titles on the door don’t fill an empty head.”

Biographers are increasingly pushing the form’s boundaries. As Emily Dickinson wrote: “Tell the truth but tell it slant.” Last year, for example, Mark Braude’s excellent The Invisible Emperor: Napoleon on Elba from Exile to Escape focused on Napoleon’s period of powerlessness and revealed a new perspective on a much-examined life. We are seeing more books that transcend category. One of my favourite books this year is Christopher Benfey’s If: The Untold Story of Kipling’s American Years which blends literary criticism and history into an original narrative about Rudyard Kipling, whom George Orwell described as a “jingo imperialist.” This book is not a cradle-to-grave biography, but rather zeroes in on Kipling’s time in Vermont when he reinvented himself as an American kind of writer. That slant rejects the traditional biographical form and illuminates Kipling’s life and legacy in a new and interesting way. Knowing that they were written in the wild kingdom of Vermont, perhaps some of us will be tempted to give those stories in The Jungle Book another try!

That’s interesting. I discussed the 2020 autobiography shortlist with Mark Athitakis recently, and he talked about how memoir has come to the fore, and that could be thought of as autobiography at a slant, as you say: pulling out a portion or theme from a life for close analysis. It’s interesting to hear that it’s also happening in biography in 2020.

Yes, yes. We’re also seeing more group biographies, signalling a more nuanced, sophisticated recognition of how people are shaped by the dynamics of their relationships.

Absolutely. The last time we spoke you introduced me to this concept of the group biography, which I hadn’t been familiar with before. And the first title we’re going to discuss today falls into this category. This is Gods of the Upper Air: How a Circle of Renegade Anthropologists Reinvented Race, Sex, and Gender in the Twentieth Century by Charles King. Perhaps you could tell us about it.

Yes. At the centre of King’s fascinating book is Columbia University’s Franz Boas (1858–1942), the father of cultural anthropology, who challenged his era’s prevailing wisdom that race, gender and sexuality were destiny. He argued against eugenics and contemporary theories of racial distinction between humans. His work culminated with his theory of relativism, which discredited the prevailing conviction that Western civilization was superior to simpler societies.

While Boas championed cultural diversity and scientific discovery, he also created an environment that inspired a circle of visionary women researchers who were pathbreaking. The book is kaleidoscopic, and its title comes from Zora Neale Hurston, one of Boas’s students whose fieldwork work led to her classic novel, Their Eyes Were Watching God. Margaret Mead’s fieldwork with adolescent girls led to her seminal work of anthropology, Coming of Age in Samoa. From her work on post-World War II Japan and Pueblo culture, Ruth Benedict shaped approaches to history and death. Ella Cara Deloria focused on Sioux folklore and legends.

“Boas championed cultural diversity and scientific discovery, and created an environment that inspired a circle of visionary women researchers”

At a time when women were beginning to chafe at the patriarchal social order, Boas encouraged them to find their work and share it with an audience. Together, they broke new ground and acknowledged differences of colour, gender, custom and ability, yet set forth an expansive vision of normalcy and humanity in a multicultural world. The pioneering work of Boas and his students is particularly interesting to consider in an increasingly tribal America.

Zora Neale Hurston wrote about her own cultural group, as did Ella Cara Deloria—so this was academic anthropology, with the benefit of insider perspectives. But why do you think it’s important to look at the lives of these particular individuals, as opposed to the evolution of ideas more generally?

By showing how these female anthropologists came to their new ideas, King enriches the experience so that readers can grasp how radical and forward-thinking they really were. Boas’s researchers came to terms with their own cultural biases and grasped the common humanity linking the people of Polynesia, the American South and Native America. King evokes the qualities that make each one of them brilliant in her own distinctive way, and gets at the alchemy that connects them. King could have done five separate biographies in one volume, but as a narrative, he makes clear how they shaped, challenged and refined one another’s ideas.

That sounds right up my street. But let’s move on. Next we have The Queen: The Forgotten Life Behind an American Myth by Josh Levin. Tell us a little bit about its subject, and why you admire it.

We need to look back to the ‘welfare queen’ meme that took root in Ronald Reagan’s failed 1976 presidential campaign. As the author of The Queen explains, the phrase was taken from the headlines of a Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter’s Chicago Tribune investigation of Linda Taylor, a Cadillac-driving, fur-clad woman who scammed the system and was code for a lazy con artist. The myth took hold and fuelled public hysteria about cadging money that honest folks had worked hard to earn. She became the poster person for welfare abuse.

Because Five Books has a very international audience, I should quickly clarify that ‘welfare’ in this context refers to state benefit payments.

Yes, thank you. In The Queen, Levin sets out to find the real Linda Taylor, but it turns out that in this case, the reality really is more interesting than the story of a self-interested politician campaigning on fake news. There really was a Cadillac-driving scam artist called Linda Taylor, and in a feat of investigative reporting Josh Levin subverts the myth and reconstructs her life. It turns out that welfare fraud was the least of her problems. Through her many aliases, Levin found that she served time in prison, and may have murdered someone.

She was both victim and victimizer; Linda Taylor was abused as a child growing up in the Jim Crow South. She abandoned her own children and is accused of selling others on the black market.

Get the weekly Five Books newsletter

Perhaps this is also a cautionary tale about daily journalism, because Linda Taylor became known to reporters after she called the Chicago police to report a burglary. Her complicated story eluded journalists of the day who wrote her off as a welfare cheat, but Levin relentlessly digs into court transcripts, old property deeds and police records story to find a troubled, complicated woman, making clear in his footnotes how he documented her elusive story. Levin’s stamina and creative search for evidence in this book is extraordinary, especially considering how elusive she was and how many identities she assumed.

Perhaps I should note how important a sympathetic imagination is for the writing of biography. In The Queen, Levin shows how the newspaper headline became a campaign issue, but that her story is far more interesting than the myth.

This is a book that operates on so many different levels. It’s about American myth-making, and it’s also a hugely revealing social and psychological story about race, segregation, identity and a damaged person who went on to damage others.

And does Levin tackle the folly of building policy off the back of singular cases like this?

The Queen is not a policy book, but the implications of the single narrative are clear. Linda Taylor came to prominence during Ronald Reagan’s 1980 campaign; his slogan at this moment when history coalesced was “Let’s make America great again.” And of course, Trump’s MAGA theme was on the horizon.

In Britain too, there are echoes of it in the ‘benefit scrounger’ narrative.

So many interesting parallels. We haven’t even gotten to the anti-immigrant populist nationalism!

Well, the third book shortlisted for the title of best biography—speaking of scandalous lives—is L.E.L.: The Lost Life and Scandalous Death of Letitia Elizabeth Landon, the Celebrated ‘Female Byron’ by Lucasta Miller. This is a biography of the poet, literary celebrity and—I think it would it be fair to call her—a provocateur.

Yes, provocateur is fair! Of this year’s National Book Critics Circle biography finalists, one could argue that L.E.L is probably the most traditional, in the sense that it’s a chronological narrative about an overlooked artist from the past. As a group of literary critics, I think we at the NBCC have a soft spot for literary biographies, or perhaps we give them their due because we fully appreciate the intellectual dexterity required to segue between the life of a writer and what she writes.

Over the years, we’ve honored quite a few of these. Recent winners have included Prairie Fires: The American Dreams of Laura Ingalls Wilder by Caroline Fraser and Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life by Ruth Franklin, both of which set a very high standard.

In L.E.L., which was the semi-anonymous nom de plume of Letitia Elizabeth Landon, Lucasta Miller sets out to reclaim Landon’s literary accomplishments and establish her as a bridge between Romanticism and Victorianism. Miller contends that Landon’s work has been overlooked and perhaps made invisible because she was regarded as popular writer whose feminine poetry was dismissed, and that she should be considered from a contemporary perspective as ‘proto-postmodern,’ sort of postmodernist in training.

Structurally, Miller does something very smart with her biography of Landon. She begins with Landon’s mysterious death—was it murder? Suicide? Accident? She turns the adage ‘chronology is your friend’ upside down and begins with the end. In suspenseful way, Miller recounts how this innocent ingenue and sex siren controlled her public image. She had three children, kept a secret from her public, who thought she was a virgin. She has sexual relations with her mentor who also promoted her career, and, as you said, she wrote scandalous poetry. Defying the norms of the day, L.E.L.’s poetry was risky, bold, flirtatious and sly.

The Atlantic described L.E.L. as “a female artist forced to earn attention by reshaping her exploitation into glamour, knowing all the while that eventually titillation will become condemnation.” This sounds still very current, to me: this question of being a sexual female in the public eye. Do you think that this is a timely book?

Very well put by The Atlantic. Some might say that men and the public used her, but I think she used them right back. Landon was a woman making a living by her pen at a time when that was frowned upon. She was this upwardly-mobile woman whose provocations distracted others from noticing her self-sufficiency.

You mentioned her upward mobility. Just before we move on I want to read a short bit of her verse, which I thought was just so funny and self-aware:

He must be rich whom I could love,

His fortune clear must be,

Whether in land or in the funds,

‘Tis all the same to me.

Perfect. While perhaps lyric sophistication is not her strength, L.E.L. really does pack a punch.

So next we’ve got Our Man: Richard Holbrooke and the End of the American Century by George Packer. It’s a biography of the American diplomat. Tell me, why does this count among the best biographies of the year?

Within the first few chapters of Our Man, I was reminded of one of my favorite biographies ever: Ronald Steel’s Walter Lippmann and the American Century. Lippmann (1889–1974) was a reporter and commentator who was also involved in government. For six decades Lippmann was at the center of American political life—where the striving, almost great diplomat Richard Holbrooke yearned to be. As different as Walter Lippmann and Richard Holbrooke may have been, biographers Steel and Packer place them within the rich context of the quarrels, triumphs, friendships and alliances of the American century.

And excuse me for my ignorance, but ‘the American century’ means when, exactly—the 20th century? Or does it start later than that?

The American century is a shorthand for roughly the 20th century, when the American empire was born, flourished, matured, and finally began to diminish by about 2000, although it could be argued that the war in Vietnam marked the decline of American influence in the world.

Steel’s Lippmann and Packer’s Holbrooke were outsized men on the world stage who separately mirrored the waxing and waning of the American empire. In Our Man, Packer does the impossible. He takes Holbrooke’s story—a mid-level ‘almost great’ diplomat who was an idealist, but also an egotist, whose insatiable need for influence mirrored America’s anxious place in the world. From Vietnam to Afghanistan and the Balkans, Holbrooke yearned for recognition, and ultimately failed in his quest to become Secretary of State.

“You just can’t help rooting for this deeply flawed man”

Packer builds a trust by breaking down the fourth wall and speaking directly to readers. “Do you mind if we hurry through the early years?” he asks. Scrupulously documented, at times Packer seems like he is channeling Holbrooke.

This is from the beginning:

Holbrooke? Yes, I knew him. I can’t get his voice out of my head. I still hear it saying, “You haven’t read that book? You really need to read it.” Saying, “I feel, and I hope this doesn’t sound too self-satisfied, that in a very difficult situation where nobody has the answer, I at least know what the overall questions and moving parts are.” Saying, “Gotta go, Hillary’s on the line.”

After Holbrooke’s death, his widow Kati Marton gave Packer her husband’s papers, journals and files. Holbrooke kept great track of his friends and foes and Packer had a truckload of his archives. I should note that although Holbrooke’s widow provided Packer access to her husband’s archives, he does not refrain from disclosing her extra-marital affairs or Holbrooke and Marton’s excessive spending.

Packer presents Holbrooke as a contradictory figure. While he craved approval by the elite, he also wanted to be a man of the people. He was very covetous of others and desperately wanted to be Secretary of State, yet alienated even his ardent supporters. He was enthralled with celebrity and money. Holbrooke’s social climbing and gross behavior are unseemly, yet Packer approaches him with such an empathic imagination, you just can’t help rooting for this deeply flawed man. He really becomes ‘Our Man’ in its best sense.

The New York Times made an interesting comment about this book: “It clocks in at more than 500 pages without the courtesy of an index. This isn’t a book you’re supposed to dip into piecemeal, but best appreciated like a novel, consumed whole.” This caught me off guard. I have never thought of reading a biography any other way. Have I been doing it wrong? Are most biographies intended to be dip-in-and-out sorts of books, reference books?

You’re not wrong! Those who read by index are really missing out, and in a whole different category are those just who look for themselves in the index, or the footnotes to see if they have been quoted.

Oh, I see.

Footnotes, though—they’re dynamite. I’m seeing more biographies with footnotes as mini-essays. It enhances my reading experience when grasp the range of sources for a biography.

In the case of Packer’s biography of Holbrooke, I can understand why there are no footnotes. Packer very effectively introduces his sources into the narrative and inspires trust in his readers.

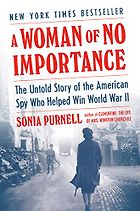

Fantastic. I think that brings us to our last biography in the 2020 list. Sonia Purnell’s A Woman of No Importance: The Untold Story of the American Spy Who Helped Win World War II. I know Sonia as the author of a biography of Boris Johnson, before he became prime minister: Just Boris: A Tale of Blonde Ambition.

What a great title! I’ll have to read it. I did read Clementine: The Life of Mrs. Winston Churchill which was excellent. As I recall, it was prodigiously researched and written in a lively style.

Tell me about this new book.

During these challenging times, tales of resistance in World War II have found a receptive audience. In the case of Sonia Purnell’s biography, Americans are keen to read about our own countryman’s heroism.

At the center of Purnell’s biography is socialite Virginia Hall of Baltimore, Maryland who had been shut out of the American diplomatic corps in the 1930s and stuck as a clerk in the State Department. Raised in affluence, she had learned to ride a horse, shoot, sail and cycle. An adventurous sort, she lost her leg below the knee in a hunting accident in Turkey. (True story: she shot herself in the foot.)

Five Books interviews are expensive to produce. If you're enjoying this interview, please support us by donating a small amount.

After the Nazis invaded France, Hall got herself there to drive ambulances which she did with her prosthetic leg, known then as a ‘peg leg’ which she named Cuthbert. Fluent in French and knowledgeable about the terrain, Hall talked her way into the Office of Strategic Services, and eventually ran spy networks and supervised air drops of weapons. She was known as ‘Madonna of the Mountains.’

Purnell recounts Hall’s spy operations so vividly that it feels like one is reading a spy novel. As Purnell’s title suggests, Hall was often underestimated and overlooked. In rescuing Virginia Hall from obscurity, the book also tells a great story about the Resistance.

It’s so interesting to me that right now there is a spate of books about women in the Resistance: for example, there’s Madame Fourcade’s Secret War by Lynne Olson and then there’s The Resistance Quartet series by Caroline Moorehead.

She sounds like a fascinating character. And actually, that’s a point I want to pick up on. As a biographer yourself, you’re in a good position to comment on what makes a person a good subject to begin with.

Great question. I grew up reading biographies in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, a city which takes its history and historical figures very seriously, so that was my initial lens, I suppose. I toggled between history and journalism, but was always drawn to biography and went to graduate school in history where it turned out that biography was not in vogue.

The great C. Vann Woodward had retired but I had loved his books Tom Watson: Agrarian Rebel and The Strange Career of Jim Crow and Mary Chesnut’s Civil War, so I visited him for tea and peppered him with questions about biography. Once I asked how I would know if I had found the perfect subject for a biography. And he said, in his amazing Southern accent: “Pick a real bitch, or real bastard, and make sure they’re dead.”

Ha! Brilliant.

Just so brilliant. I mean, what he was saying to me is: No hagiography or rescue mission, and you need to have the full measure of a life. I don’t really consider books about living people to be real biographies, because it’s not the full, measurable life. Also, I’d like to be able to trust my sources and all sources have agendas. So that’s how I think of biography.

That brings me to one more question I wanted to run by you. Coming back to the Packer book: I believe Packer was a friend of Holbrooke. Do you think a biographer writing about somebody they actually knew in real life is at an advantage or a disadvantage?

It probably works multiple ways. I personally prefer the subject to be dead and not someone I know. Packer did a New Yorker profile of Holbrooke and he was the one chosen to receive his papers. Maybe it’s just an individual case, but I feel that Packer is so honest in the book. He puts himself in it, and talks to the readers, so I don’t see it as a problem. I see it as: he has empathy, an understanding of Holbrooke, but it’s not like they were best friends. They just knew each other, I think.

It gets us to another interesting question, which is about access. Many people say access is really important in a biography. Access to interviewees, or access to the source. My friend Adam Cohen and I wrote a biography, and our character, Mayor Richard J. Daley, was dead. Then we tried to talk to his family, and we had a few sit downs—little brief ones—but they really cut us off. I was worried about that, but then I realized that I kind of knew what they were going to say anyway.

“Time reveals. I guess that’s why you can’t really rush a biography”

Right now I’m working on the 19th century, where nobody can talk back. I’m trying to read between the lines; it’s not just what a character’s writing in a letter, but also to whom they’re writing it. That says something intangible about a person. I mean, you wouldn’t put it in a biography, but it informs your sensibility. A friend of mine said that the process of not getting an interview with the Daley family was its own education. And, yes, in being repeatedly rebuffed, and how that was done, so much was revealed in the process.

Time reveals. I guess that’s why you can’t really rush a biography, because time has to reveal itself about a person.

You must have quite a wide perspective of the field at the moment. Do you feel optimistic about the state of biography in 2020?

Oh yes. Yes, I really do. I think that we’ve gotten past the cradle-to-grave biography. I mean, they’ll always been popping up, the dutiful ones, but increasingly these biographies are at a slant, or more episodic, or and I think that has brought a new energy to the genre.

So I feel optimistic about that, but I am worried about the problem of email and archives. I can’t even convey the joy of going into an archive, and finding these handwritten, impossible-to-read letters. They’re so good. I have to hand-type them, fantastic. Without letters, diaries and documents, I am so worried that so much great history is going to be lost.

Yes, I worry about this too. There’s an ephemerality to a lot of written discourse these days. So much of our own personal archives can be lost if one loses a password. We live our lives online, and then it disappears down the drain.

I mean, journalism was fantastically helpful when I wrote my book about Mayor Richard J. Daley and the making of modern Chicago, but so much of what appears now is on Twitter. It doesn’t even make it into the papers. The other thing I’ll say is that if you pick a day in history, say . . . August 23rd, 1968. It was during the Democratic Convention and I have a folder several feet wide of different newspaper articles covering the day’s events from wildly different perspectives. That doesn’t exist anymore. We’ve talked about the local news crisis, and I think we will see in a generation that books are really suffering, definitely. So I am so optimistic, but I’m worried at the same time.

Part of our best books of 2020 series.

Interview by Cal Flyn, Deputy Editor

March 1, 2020

Five Books aims to keep its book recommendations and interviews up to date. If you are the interviewee and would like to update your choice of books (or even just what you say about them) please email us at [email protected]