What is it like to be a poet today?

It’s the same old pen and page, or stylus and parchment, as ever, regardless of the different ways it gets distributed or read. Just as hard one day, and easy the next, as fate or luck or effort decides.

The reception seems a lot patchier than it used to be, as regards newspapers and magazines. It can be a lonely life, so I guess that’s the appeal of the social media, which have created an atmospheric change. Often a worse one: the tweet of 240 characters is not a useful way of discussing issues of any aesthetic or political complexity, and too often results in mobbing, take-downs and self-righteous conformism. What should be a democratising medium creates its own little hierarchies. Noise it would be best to switch off before trying to write a poem.

You’ve just released a new collection of poetry, Anomaly. Tell me a bit about it. Are these poems about your own life?

My life story, such as it is, hasn’t been a central feature of any of my collections, though it might enter at the margin of quite a few poems or prompt them. There are a couple of poems about my parents who died during the time of writing. One about my father is also an offensive account of the architecture of a nearby church and then turns to the Second World War; the other about my mother concerns a Liverpool park . . . private lives (though not so private now) and public spaces.

Another poem, ‘Urban Field’, which I suppose could be taken as personal, is set in a local café, but that has a view of horses, then seems to end up as a lament for old age and ill health. They ought to put me on cigarette packets.

These poems are local but much of the collection is set in other places—Italy, Spain, Slovenia, France.

You do a lot of translation, too.

Yes, also in this collection, which includes translations from Machado, Baudelaire, Aldo Palazzeschi, Valerio Magrelli and Antonella Anedda.

Perhaps translation is a way of escaping from the self, or personality, to adapt Eliot’s remark about poetry. If you’re translating a poem, you have to adjust to that other voice. I’ve never much wanted that Lowellian thing of imposing my own voice, but at the same time, I’ve only got my voice to work with—to shift towards the other voice.

You have to hear that other voice. The point with Robert Lowell’s Imitations is that he doesn’t hear any of the voices, because he doesn’t know the languages. He’s doing his thing, which he does very well, but he’s not setting himself this problem. That’s not intended as disapproval: Lowell’s work is mostly fun for everyone else; it’s enriching, and he brings something to it. You might say better him than a talentless person who does know the language. But he’s using other people’s translations to create his art.

And for you, it’s different?

Not entirely. I know the process both ways. I’ve translated from languages I don’t know and those that I do.

Translating from a language you don’t know is quite liberating, because you aren’t accountable to the same extent. However, my feeling is that you do a better job—or at least I do—knowing the other language. You might be inhibited at the outset by the sheer power of the original, but you can better accord what you’re doing with it.

Going back to what I was saying earlier, with translation as with poems, I tend to prefer looking out than in. This might sound like an ethical point but it isn’t really, it’s more a question of temperament.

What tends to occasion a new collection for you? Is it governed by time, or more by theme—how do you know when it’s ready?

Difficult to say. There has to be a cut-off point. It’s not as arbitrary as the number of poems or pages, rather that the book has to have a shape, though that shape changes as I rearrange things. In the case of this collection, I dropped a few after I’d submitted it—in agreement with my editor—but then smuggled in two or three latecomers, which I realised the book needed. Most of my books have, however, ended up around the same length, and that may be mainly to do with what I was trying to say before: that I can see a shape to it.

I hope with each book, that’s a different shape. And that could have, and certainly has had in more than a couple of my books, a thematic element—volcanoes in one, prisons, invasions and obituaries in another. What usually happens after is I shut up shop for a year or so, and have to put up with a bit of a dead stretch. I console myself by thinking it’s an attempt to move on to somewhere else.

Does that count for translation as well?

Yes. It could be said to deplete energy. Lately I’ve been doing a lot of prose translation, and have just finished the six books that make up Giorgio Bassani’s The Novel of Ferrara: that’s a lot of words, of work, a lot of hours, of months sitting uncomfortably at the screen. Ill-paid, unhealthy work. If anyone notices the translator, it’s often enough to deliver a reprimand.

But you could also say it’s energising. I’ve translated books of poems by Valerio Magrelli and Antonella Anedda, and among other things a verse play by Pier Paolo Pasolini. Prose or poem, if you’re lucky enough, as I have always been, to translate a good writer, it surely has to expand your horizons. Having overcome one problem in translation equips you better for the next, and may even help with obstacles in your own writing.

Let’s move on to your five book choices. Three of your picks are from 2018, and two are from 2010.

This time lag has something to do with the nature of poetry. Even if a book is making something of a splash, you might not want to read it until you’re ready. And this last year, the demands of translating and of putting together a book of essays have left me even less time than usual for contemporary poetry. Which means there’s probably good work I haven’t read, or haven’t read with sufficient concentration to know how I feel about it.

Another factor—which is true for everyone—is that poetry collections need to settle in your mind. If you’re asked to review it, you accelerate that process, but if you’re reading for pleasure or interest, it can be a slightly more diffuse experience.

However, two books I have read, prior to their publication, and hugely admired but can’t really include—one, The Return of the Gift, is by my brother-in-law Michael O’Neill, who died this December. It includes a clear-eyed and courageous sequence ‘From the Cancer Diary’ and a great deal else. The other, another extraordinary book, not on my list because it’s in Italian, and I’m her translator, is Antonella Anedda’s Historiae, which considers various contemporary conflicts and traumas via the optics of Tacitus and classical history.

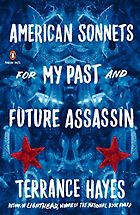

First we have Terrance Hayes, who wrote a collection called American Sonnets for My Past and Future Assassin (2018).

I’ve read that in this book he’s addressing the first period, day by day, of Trump’s presidency, so they are very much current. American Sonnets for My Past and Future Assassin interrogates issues of race, gender, sexuality and politics in America.

There are really a hundred ways in which, despite having the ‘right’ ideas, a poem can go wrong. But the energy, agility and invention of Hayes’s work guards against most of them, and emphatically win the reader over. He’s as unafraid to tackle whatever comes his way as he is to grapple with the formal history of these sonnets. They’re vivid, unrhymed fourteen-liners.

“There are really a hundred ways in which, despite having the ‘right’ ideas, a poem can go wrong. But the energy, agility and invention of Hayes’s work guards against most of them”

Are they ‘American Sonnets’ because of their subject matter, or their form? I wouldn’t consider the unrhymed form especially ‘American’, but the allusion may have to do with other forebears such as Rita Dove’s Mother Love or Lowell’s History. By comparison, Lowell sounds heavy and armour-plated. What comes over in Hayes is an attraction and a resistance to the form, or as one poem puts it:

I lock you in an American sonnet that is part prison,

Part panic closet, a little room in a house set aflame.

I lock you in a form that is part music box, part meat

Grinder

where any reassurance of the contained form is set against images of violence it barely seems to keep at bay.

He is playing with the form and history of the sonnet with great awareness and making it responsive to the political moment: the verbal wit and play, and the urgency are what struck me most. It looks to me like one of the strongest collections I’ve read for some time.

We might turn next to Michael Hofmann, with One Lark, One Horse. He’s a seasoned author, isn’t he?

Yes, a wonderful poet and translator. Admirers of Hofmann’s work have waited a long time for this book—it’s been something like 20 years since his last collection. But that time has been filled with a succession of outstanding translations of poetry and novels, the most recent of which is Alfred Döblin’s Berlin Alexanderplatz. I’ve admired his work since his first book, Nights in the Iron Hotel (1984). It was written in his early twenties, and he already seemed fully formed as a poet. Even there he moves between cultures and languages with ease and rapidity, in a way none of his contemporaries would have thought of doing, or been able to.

Get the weekly Five Books newsletter

The new work is as challenging and original as ever. It takes on, a bit like Hayes, the present moment, and with breathtaking reach and virtuosity: Trump’s America, Brexit—politically a confederacy of dunces. He turns the ugliest, dumbest material (the detritus of everyday life, from acronyms to social media) into grimly brilliant assemblages.

Of all my contemporaries, it seems he’s the one that’s most heard and attended to that famous injunction of Rimbaud’s: ‘Il faut être absolument moderne’. (Perhaps in my own work, I’ve been perversely taking the opposite advice: ‘Il faut être absolument ancien’!) But this book has been worth waiting for, even by his own very high standards.

Is that why we’ve waited so long for this new collection, Hofmann’s own high standards? Or is it just that he works in several different modes, prose as well as poetry?

Well, my own experience, as I said before, is that translating can be energising but it can also be exhausting. And Hofmann has done way more than anyone I can think of—it’s a dizzying tower of books. Who knows what the reasons are? The thing is, real poets aren’t—or shouldn’t be—on any schedule where they have to turn out a volume every few years. It’s refreshing to see a poet whose writing is governed by some kind of inner necessity.

“Real poets aren’t—or shouldn’t be—on any schedule . . . It’s refreshing to see a poet whose writing is governed by some kind of inner necessity”

I think in an interview somewhere, he said he didn’t want to add to the European ‘butter mountain’. [Laughs.] Even if we might think a bit more kindly of the EU and its trade agreements these days. In this book, as I said, he touches on Brexit—he’s got the means adequate for dealing with the totally idiotic politics we’re living through, but the book has a huge span inclusive of Australia, North America and Germany as well, and its inclusiveness is as much linguistic as cultural.

How do contemporary political events like Brexit or Trump’s election creep into modern poetry? It doesn’t seem to me that you would specifically designate either Hayes or Hofmann as a ‘political poet’, but the themes are there all the same.

I suppose the politics are foisted on writers by the present moment. Hofmann’s work has always looked more to the contemporary than the past, and that almost inevitably involves politics.

Five Books interviews are expensive to produce. If you're enjoying this interview, please support us by donating a small amount.

I don’t mean that poets are obliged to wear a badge of party adherence, but they are engaging with their age. It would surprise me for any poet if there wasn’t at least some significant element of that, however refracted or disguised.

Next, you picked The House With Only an Attic and a Basement by Kathryn Maris. Tell us why you chose it.

This is her third book, and it shows her coming into her own. Its humor is more dismaying than the others I’ve chosen, its control of language ever more precise. Her often dysfunctional speakers stumble into catastrophes with their eyes wide open.

A fair number of reviewers, I’ve noticed, have taken these monologues as thinly veiled autobiography. Whether there’s any personal overlap or not, it seems to me that the poems clearly indicate a ventriloquist approach to their material. The book has three poems called ‘Catherine and Her Wheel’. It sounds like the author’s own name, but visually isn’t the same, which is a good example of the way in which the self is used in her poetry, but actually displaced. Not to perceive this would be to lose half of the enjoyment, as well as its disturbance. If you read them thinking this is autobiography, so much of the play of the poems is lost.

It sounds like a reductive way to read contemporary poetry, and I especially see it when women poets are reviewed—it’s so commonly assumed that autobiographical material is just being mapped onto stanzas.

It’s not an uncommon general assumption since the days of the Confessional poets (Sexton, Plath, Lowell and Berryman being the prime examples). Even that label is a misnomer and a mis-appreciation of what these poets were each of them doing very differently.

Maris has this lovely play, in the third of those Catherine Wheel poems, on the Spanish expression “nada de nada”:

that there was nothing, that there was ‘nada de nada’,

the most perfect Spanish expression, the most beautiful

and poetic circle, the nothing wheel,

the wheel I have carried through all routes of my life, the wheel

I was fundamentally wedded to, my true beloved,

watch me touch it now look at it look at it: nothing.

Like the Spanish expression with its emptying repetition, the repetition of the last line spins and accelerates, losing even the punctuation. What I like best is the way the vanity the collection addresses, among other things, is exposed, and edgy, and teetering on the abyss. I hadn’t really questioned myself about its relation to contemporary politics, but it feels current without explicitly addressing the subject. That may well be how, in many cases, poetry deals with the contemporary.

Let’s move on to your next choice, which isn’t a slim volume but the full Collected Poems of Arun Kolatkar. For those who haven’t heard of him, tell us about Kolatkar and why you chose this book.

Another tardy encounter, but somehow with Kolatkar that seems okay. Despite his prolific output, both in English and Marathi, he seems to have been extremely reluctant to publish except in small presses, so his poetry was always slow to arrive to all but his devoted circle of fellow poets and readers. But it’s well worth the wait, and this Collected Poems has the bonus of the poet Arvind Khrishna Mehrotra’s moving memoir and introduction.

Kolatkar was born in 1931 in Kolaphur, but moved to Bombay at the age of eighteen and there he remained till his death in 2004. His poems, panoptic and casually incisive, are a celebration of the city’s seedy and burgeoning sprawl. Almost anywhere you open the book there are treasures of wry observation and breathtakingly inventive imagery. Just as one example, ‘Lice’, that compares with Rimbaud’s great poem on the same topic, has the speaker envious of a newly released prisoner who is being deloused by a beautiful girl in the street.

In three cinematic sections, it starts with a description of the girl “like a stick of cinnamon . . . sitting on that concrete block/ as if it were a throne”, then dwells rancorously on “her dirty no-good lover” (“Just look at him, the yob…”) and in its final section enters the dreamy state of this undeserving youth as he drifts off, while her hands move through his hair, into “a mossy cave . . . booby trapped with rainbows,/ and hears the distant bark of police dogs.” This extraordinarily mobile and seemingly inexhaustible imagination can be heard throughout the book.

Last, we have a work by Anne Carson called Nox—I say ‘work’ because to call it merely a ‘collection’ or ‘book’ doesn’t seem right. Tell us about Nox as a physical object.

Essentially, it’s a box. (Rhymes with Nox.) Inside the box is a connected, folded concertina of pages. The recto and the verso often have very different functions. On one side of the page—the verso—she often gives a dictionary definition for the 63 words of Catullus’s poem, which is supposedly an elegy for his brother. So, it’s like a dictionary gloss, but it’s an imitation, to an extent, because she keeps on giving definitions that include the idea of ‘nox’, of night. Though I haven’t checked with a big Latin dictionary, I imagine many of them are quite accurate, but tilted, or slanted.

On the other side of the page, we get an account—appropriately enough, for a meditation on Catullus’s poem—of her own brother’s death. She pieces together fragments of his life. Unlike in Catullus, who names almost everybody but doesn’t name his brother in the poem, Carson names her brother from the outset.

The reader has to piece together the fragmented narrative, and some of the pages are formatted like photocopied, torn pages—the scattered leaves of a life. It’s like a memorial album, written in prose. If I’m not wrong, the exception is Catullus’s poem #101 to his brother. It’s an interesting, intelligent, but very flat translation. It isn’t a distinguished bit of poetry—I think you could find much more impressive translations of it. But it’s one that’s trying to accord itself with all of the nuances of each of the words. A map, perhaps.

It’s an exercise not in the virtuosity of translation, but a more humble approach to the original, if you like, which relates to what I was talking about with the idea of knowing or not knowing a language when translating. She uses not only Catullus, but also bits of Herodotus and Plutarch in an ongoing meditation on history.

She brings the knowledge she has as a Classics professor to bear on the work, yet it doesn’t feel like a weighty, academic tome—it’s light on its feet. She’s good, and has been from the start of her career, at what she excises or leaves out. The absences—the gaps—are crucially operative in her poems. That’s true also of “The Glass Essay” in Glass, Irony and God.

You could say that Carson’s work has been a spur to the idea of the ‘lyric essay’. In Glass, Irony and God, there’s an academic essay at the end about the silencing of women’s voices in ancient Greek culture. It’s an engaging and polemical essay. As to whether you read it as poetry or not—I certainly didn’t, and probably still wouldn’t. I’m not really hung up on the nomenclature of ‘this is poetry; this isn’t’, but, having said that, I think there is a difference.

Five Books interviews are expensive to produce. If you're enjoying this interview, please support us by donating a small amount.

I’m not even sure if you have to consider Nox a poem, but it occupies that category. She uses prose so skillfully. This fragmentary element is a disruptive force to the flow of narrative. Therefore, you can’t quite read it as a short story or as a life-writing account. And it’s galvanised by this searing focus on Catullus.

Carson’s been something of a pioneer, whether or not you would call this work or others examples of the ‘lyric essay’. Clearly Claudia Rankine thinks of Citizen as a ‘lyric’, given the subtitle. That has spawned a whole number of younger poets writing lyric essays. But in each case what the work achieves is far more important than the category it’s assigned.

On that subject, I’ve thought sometimes that some of the best literary criticism seems to reach an almost purely poetic state of meditation, for example, Seamus Heaney on Robert Frost, or the critical writings of Geoffrey Hill.

Though certainly the writings of a poet, I’d see Hill’s prose, compacted as it is, as closer to the academic. (Not for me a criticism, though I find his prose hard work.) Heaney always had that kind of lyrical gift in his criticism. I think perhaps the finest example of that quality can be found in Osip Mandelstam’s Conversations with Dante. From an intimate knowledge of Dante and Italian (acquired it seems on a youthful visit), he throws out metaphor after metaphor all of which are beautifully clarificatory about the movement of the Commedia. It’s one of the great masterpieces of poets’ prose in that mode.

I wouldn’t deny this is a resource of poets writing on poetry. On the other hand, I also value a type of academic prose which doesn’t have a lyrical element, which is a solid work of scholarship: good critics who know how to use language well, and are interested to illuminate the text.

“To me, the work of Rimbaud is the greatest example of the prose poem.”

However, I’m also interested in some of the effects of hybrid forms of prose and poetry. I translate Antonella Anedda, and from an early stage—prior to Carson even, though she’s younger—she’s been using prose interspersed with poetry.

To me, the work of Rimbaud, who for some reason keeps cropping up here, is the greatest example of the prose poem. He’s close to the beginning and to me, the apex of the prose poem. Perhaps that sounds rather valedictory, but I think he just got hold of the form in all its luminosity and did more with it than anyone has done since. In the UK, we’ve had Geoffrey Hill’s Mercian Hymns, which I think is very fine. I’m probably missing quite a number of exceptions, but essentially, it’s not a form that’s flourished in this country—more elsewhere, and France is really the centre of it, I think.

Do you have a sense of whether, in recent years, certain poetic forms have emerged as dominant in the work of poets you most admire? Is the sonnet or the villanelle making a comeback, for example?

Somehow the idea of any ‘dominant’ form makes me feel uneasy. Poets have to find their own forms, or rather poems have to.

But the sonnet is a durable form as we’ve seen with Hayes, because it’s so flexible and compact. Its slight imbalance, entailed by the traditional eight-six line split, allows for so much variation. As we know, the history of early modern English poetry, with Wyatt and Surrey, starts with their responses to Petrarch.

Over here, it may have been given a new lease of life with Paul Muldoon, with his inventive rhyming and stanzaic re-arrangements of the form. There are quite a few poets since, like Don Paterson, who’ve experimented fruitfully with the sonnet.

It requires compression and speed: you can’t waste time in a sonnet, because every loose phrase shows. But that’s true of all kinds of short poem. Perhaps US poetry is more resistant to these inherited forms from Whitman onwards: at least one prominent tradition there is to invent form from scratch. And all this talk about sonnets that I’ve indulged in makes me warm to that.

Five Books aims to keep its book recommendations and interviews up to date. If you are the interviewee and would like to update your choice of books (or even just what you say about them) please email us at [email protected]