Let me start by welcoming you back to Five Books, Caroline; previously you recommend us some classic Christmas mysteries. This time, you’ve chosen five of the best wartime mystery books, having recently launched a new series of your critically-acclaimed podcast Shedunnit called ‘The Queens of Crime at War.’ Was the Second World War a particularly rich time for detective fiction?

The ‘golden age’ of detective fiction is generally talked about as being between about 1918 and 1939, or 1940. The Second World War is considered a hard stop. But that’s very much something that we’ve imposed. If you were a crime fiction fan in 1939, you wouldn’t have immediately thought: ‘Oh well, this genre is over.’ People still loved reading detective fiction. These books were really popular.

As the war took hold, people really wanted to read what was called in newspaper reports of the time, the ‘Literature of Escape.’ And a lot of the queens of crime—the most popular writers in that genre at the time—were still very much writing and very popular. So I was interested to look at what happened at the end of the Golden Age.

What you said about escapist books finding popularity during stressful periods really rings true today. I know we’ve seen a spike in interest in romance, crime fiction and other ‘cosy’ books during the pandemic. I love the range of books you’ve selected for us, shall we get straight to it? The first wartime mystery book you’ve selected for us is Checkmate to Murder by E.C.R. Lorac. Published in 1944, this centres on a murder during the London blackout. Why did you recommend this book?

I think this is my favourite novel from the 1940s. It’s not a wartime mystery written from the comfort of the 1960s, looking back; the author was writing as the war was still going on, and she didn’t know what was going to happen—what the outcome was going to be. I find that really interesting to think about.

As you say, it’s set in the blackout. A group of friends are gathered in an artist’s studio one evening. They’re all doing different things: the artist has finally persuaded an actor friend to come and pose for a portrait, the artist’s sister is in the kitchen making dinner, and a couple of others are playing a chess game. That’s where the ‘checkmate’ of the title comes from.

Get the weekly Five Books newsletter

It’s one of those classic murder mystery situations where technically all of those people could vouch for the other: on paper, they’re all within sight of each other. But once you start to unravel it, questions arise: Can the portrait painter really see the chess players? Was his sister in the kitchen the whole time? That kind of thing.

The studio is in the garden of this very rundown house in North London. The whole street has been condemned for redevelopment, but there’s this one old man who has clung on in this house, he will not sell. So the whole street is abandoned, apart from that one house. This old man lives alone, in one room. He’s in bed, most of the time. And he gets shot dead on this evening. There’s no one around, seemingly, apart from this group out in the studio in the garden. That’s the setup.

There’s one other detail about it that I find really interesting, which is that the murder is discovered by a special constable. A special constable was a kind of volunteer policeman who joined up to help with the shortage of police during the war, after men were recruited into the armed forces. They were often, I think, retired police officers, or people who’d worked in policing overseas. They had this odd status where the only thing they were really allowed to do is police the blackout. They’re not really supposed to solve crimes. So when the real Scotland Yard detectives turn up, there’s this odd professional tension between them, which is very peculiar to wartime. I’ve never really seen that in a detective novel anywhere else. The characters in the studio don’t like the special constable at all either, because he’s very officious and seems inclined to accuse people, which is interesting.

I noticed that this, and a couple of your other titles, have been republished by the British Library.

Yes. The British Library has this imprint called ‘Crime Classics’, edited by Martin Edwards. A lot of the books that they republish were previously unavailable—out of print, or very hard to get hold of. They’ve brought them back in a nice paperback range. If you’re looking for a classic murder mystery that isn’t by Agatha Christie, then that’s a good place to go.

Great. Next on your list of the best wartime mysteries is Margery Allingham’s book Traitor’s Purse. Could you talk us through it?

Yes. This was her first wartime mystery of two. She wrote it in late 1939, or early 1940. It features her regular detective Albert Campion, who she’d been writing about since the late 1920s. He’s in, I think, at least ten books through the 1920s and 1930s. At the beginning, she’s writing him as almost a parody of an aristocratic amateur sleuth. He’s very silly. That slowly morphs into him becoming a more serious, rounded character. His silliness becomes a facade that he puts on when he doesn’t want people to realize that he’s actually very astute.

What’s so interesting about this book is that she completely formally deconstructs the detective novel as people have known it to date. It begins with Campion waking up in hospital with total amnesia. He doesn’t know who he is, or where he is, or why he’s there. He’s had an accident, he’s suffered a head injury, and he has no idea what’s going on. But he just has this overwhelming feeling that there’s something he’s supposed to be doing — something really important. He doesn’t know what it is. He has to piece together his own identity, and the case that he must be working on, from what he overhears other people saying and from contextual clues, and from who comes to see him in hospital. He’s solving the mystery of himself at the same time as trying to solve a wartime mystery.

“The classic whodunnit had been domestic. But wartime enforced a much more communal way of living”

In it, there’s a gang of counterfeit currency conspirators trying to flood Britain with fake money in order to destabilize the economy, and make Britain more likely to be defeated in the war. Interestingly, lots of the reviews for this book at the time were really good, but the one thing that comes up a lot is people saying that it’s all very far-fetched. Obviously, people at the time thought, there couldn’t be secret Nazi collaborators making fake coins or dropping fake banknotes. But then about 15 years later, Allingham was sent a press cutting from a German fan saying ‘no, actually you were right. This really was happening.’ It was called Operation Bernhard. It was absolutely real. She’d imagined something that was actually going on.

What a very clever book. In so many different ways. It sounds great. I know that Agatha Christie called Allingham “a shining light”: was she a writer’s writer?

I think so. Yes. I think J.K. Rowling has also cited Allingham as her favourite of all the Golden Age crime writers. Allingham wasn’t content to just churn out books in the same old classic mould. She was always trying to do something a bit different each time.

Actually her publishers really hated this about her. She was supposed to be on the crime list, but a couple of times they said: ‘We can’t put this out as a crime novel—people will feel really shortchanged.’ They would move her to the general literature list. She was always a bit awkward in that sense.

Good for her. Speaking of Christie, let’s move on to N or M? by Agatha Christie, which I think is her only wartime mystery.

In a way. Christie was incredibly prolific during the Second World War. She always maintained at least a book a year over her whole career, but during the late 1930s, early 1940s, she was writing two and sometimes three. She wrote what she intended to be the last Poirot and the last Marple mysteries in the early 1940s, and then they were put away in a bank vault, as an insurance policy ‘in case of my death.’ She signed over the copyright—the Poirot to her husband and the Marple to her daughter. The idea was that if she were to be killed, their posthumous publication would make a lot of money and that would see that her loved ones would be okay. So in addition to the books that she actually published, she was writing extra ones, in case of emergency. As it happened, she lived into the 1970s, and the books weren’t published until then.

But, yes, N or M? is the only book she wrote during the war that’s actually about the war. She completely ignores it in all of her other ones. She comes back to it, from the later 1940s, but not at the time. N or M? is a Tommy and Tuppence novel, who are recurring characters for her but far less well known than Hercule Poirot or Miss Marple.

Get the weekly Five Books newsletter

They’re a married couple, and they’re interesting because they actually age through the books. Poirot never ages. But the first time we meet Tommy and Tuppence in The Secret Adversary in 1922, they are young, they’re not married, they come to fall in love over the course of the case that they solve. And then the next time, in Partners in Crime, they’re married, they’re about to have a child. It then jumps forward, and in N or M? that child is much older, and they’re feeling quite bored. They used to be involved in espionage, and now there’s a war and no one seems to want them. Then they are recruited, or rather, Tommy is recruited to help find a mole in the British intelligence services. And Tuppence decides that she’s not being left behind, so she gets dressed up incognito, goes to join him, and they pursue this case together. It is all about finding fifth columnists. It was the one time that Christie tried to write about the war while it was happening, and she does it in a more lighthearted tone. All the Tommy and Tuppence books are that way.

One interesting thing about this book is that there’s a character in it called Major Bletchley, who freaked out the British intelligence service. They wondered whether she somehow knew what was going on at Bletchley Park, since she was very good friends with someone who was actually working there, a Cambridge mathematician called Dilly Knox, who was one of the leading codebreakers. They thought he must have said something, but when she was asked why she’d named this character in her book Major Bletchley, she said, ‘Well, I was once on a train from Oxford to London and broke down and I was stuck in Bletchley station. It was such an inconvenience, it was awful, I hated it. So I gave this really boring character the name Bletchley.” She had no idea. It was a coincidence, but it evidently bothered them very much.

That’s funny. It does seem like these mystery books begin to trespass into spy novel territory. I suppose crime fiction set during wartime inevitably becomes tied up in larger political questions.

That’s definitely true. I think a question that lots of these writers were trying to solve was that, up to this point, the classic whodunnit had been domestic, albeit sometimes in the aristocratic, country house sense. But wartime enforced a much more communal way of living. Everyone had to do the blackout, or else it wasn’t going to work, that kind of thing. It was a bit harder to send a load of characters off to a remote country house and just keep them there. There was a sense that you had to be part of the world.

Let’s talk about Michael Gilbert’s wartime mystery Death in Captivity, which is a book set in a 1943 prisoner of war camp in northern Italy. So it’s a far cry from a country house weekend.

This is based very directly on Michael Gilbert’s own experience of being a prisoner of war during the Second World War. He served in the armed forces, was captured in Italy, and was in a prisoner of war camp. While he was there, he had the realisation that in the work of the detective novelists of the 1920s and 1930s, the most difficult thing was to draw a plausible circle around your suspects. You have to do that in order for such a book to be good: it has to be one of only, say, these eight people, and there’s no way that a random homicidal maniac walked in off the street, did it, and left, because that’s not interesting.

Right. That’s called a ‘closed circle’ mystery, right?

Exactly. So he realised that a really good and unusual example of the closed circle is the prisoner of war camp. Entry and exit is very tightly controlled. The whole point is that no one gets in or out, so that’s what he decided to work with. He wrote it later, but it reflects his own wartime experiences..

And it’s a really good mystery, but with the added context of being set in an unusual place, and based on his unusual experiences during the war. It’s a nice little record of something you don’t necessarily get to read firsthand all the time.

Well you definitely don’t tend to see prisoner of war camps in a light fiction context.

No. And I was particularly drawn to it because my grandfather was in an Italian prisoner of war camp. So that’s why I initially picked it off the shelf. He was a very long way from home: he was from Johannesburg and enlisted there. His unit was brought to Europe, where he was captured, and placed in a prisoner of war camp in Italy. He then escaped, and tried to walk down the length of Italy to meet the Allies, who were coming north, but he didn’t make it, he got captured again. That time he got taken to Munich, and he spent the rest of the war in a camp in Munich. Having heard those stories from him, I was interested to read a whodunnit based on such similar experiences.

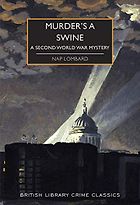

I can see that. What an incredible story. I think that might bring us to Murder’s a Swine, a wartime mystery book by Nap Lombard. Nap Lombard was actually a pen name for a married couple, is that right?

Yes, two writers, Pamela Hansford Johnson and Gordon Neil Stewart. She was a British poet and novelist, and he was a journalist, originally from Australia. They got married in 1936, and they lived in West London. They were both, I think, quite active in civil defence and volunteering. They both signed up to be ARP wardens as soon as the war started. It was that experience, or particularly Pamela’s experiences, that gave them the scenario for this.

They wrote two detective novels together as Nap Lombard. The first one was called Tidy Death, which is basically impossible to get. For whatever reason, the British Library decided to republish the second one first, and that’s Murder’s a Swine. This has, again, a brilliant, and very accurate contemporary feeling. The detectives are a married couple, and you can imagine that Pamela and Neil are giving some of their own relationship to Andrew and Agnes in the book.

“Agatha Christie, as the most prominent and best-selling crime writer of the time, was under a lot of pressure not to write about the war”

They live in a block of London flats, where they don’t know many of their neighbours. Everything is very transient; people are there when they’re on leave. Who is anyone, really? As the book opens, Agnes locks herself out. And as she’s waiting for the landlord of the building to come and let her in, she decides to go and wait in the air raid shelter out of the rain. She meets a warden who’s also hanging out down there, and together they find that someone has shoved a body in among the sandbags. The mystery unravels from there.

Why is it called ‘Murder’s a Swine’? I see that the American title was ‘The Grinning Pig.’

It becomes clear early on that the murderer is somebody on a twisted revenge vendetta. Every time something awful happens, there’s some kind of pig connection. At one point, someone’s being terrorized by a pig head that keeps appearing at the window of their flat in the night. It’s got some scarier moments, but overall it’s quite a light hearted book.

Well, thank you for these recommendations. One final question I wanted to ask was whether you think it was difficult for these writers to pitch their books correctly: is it hard to write an escapist book about a murder in a time of darkness and death?

I think so. I’ve heard that Christie, as the most prominent and best-selling crime writer of the time, was under a lot of pressure not to write about the war. Though, as you can see, other writers were not bothered; E.C.R. Lorac wrote several books about the war, and most of her books of the time mention it at some point.

I think Christie, in particular, had been scared off early on, because in 1939 she had a contract to write a series of 12 short stories for The Strand magazine. You can buy them now as a collection called The Labours of Hercules; each one is a Poirot story in which he solves a case that mimics the classical myth of the labours of Hercules. The twelfth story she wrote for that serialisation is about Hitler, or a Hitler-like figure who is the leader of a fascist organisation in a central European country, and The Strand refused to publish it. Her agent made sure she still got paid, but only 11 stories ever appeared. And for the subsequent anthology, she wrote a new twelfth story in its place.

The Hitler story has since been republished in the academic John Curran’s edited edition of her notebooks. But I think she and her agent were wary after that—that things would be rejected for serialisation, or that readers would not want to read them, if they were too directly about the realities of the war at that moment. Other writers perhaps didn’t have that cautionary experience. But I do think they thought about it a lot, particularly among those writing detective fiction. They knew they were there to entertain and to comfort, and were aware that people read their books for recreation. So giving them serious dollops of wartime content was maybe not what they were for.

But at the same time, Allingham in particular didn’t seem able to think about anything else—quite understandably. Probably for her, the choice was to give detective fiction a rest until after the war, or include the war in her mysteries. And she really needed the money, so she kept them coming. I do find it interesting, though, that in a genre where you are essentially making light of death anyway, to a greater or lesser extent, that this was something that troubled people.

Interview by Cal Flyn, Deputy Editor

November 4, 2021. Updated: April 9, 2025

Five Books aims to keep its book recommendations and interviews up to date. If you are the interviewee and would like to update your choice of books (or even just what you say about them) please email us at [email protected]

Five Books interviews are expensive to produce. If you've enjoyed this interview, please support us by donating a small amount.