You’ve agreed to take on the topic of ‘transnational literature.’ I’d like to start our discussion by asking you to define it.

There is clearly a lot of academic writing on this subject, I am not familiar with it at all. I tend to take ideas like transnational literature and define them for myself. I think of transnational literature as writing which spans the borders of countries and blurs lines between them.

Exit West, your latest novel, certainly fits within the rubric of transnational literature. Please tell us about it.

It’s a novel that imagines a world where people can suddenly move beyond their borders. We follow two characters, Nadia and Saeed, who flee an unnamed city that is undergoing a political apocalypse and migrate, first to Mykonos and then to Britain and then to California. And, as they’re migrating, millions and perhaps billions of other people are migrating as well. So the novel is an attempt to look at the universality of migration and it is about a world where physical migration is becoming universal.

Your literary reflexes seem attuned to transnational cultural crises. In The Reluctant Fundamentalist you explore the radicalization of a man who once felt at home in Manhattan. In How to Get Filthy Rich in Rising East Asia you explore the characters who drive hotly developing economies. Now, in Exit West, you focus on the plight of refugees. Fair characterization?

It probably is a fair characterization. The stuff that I’m thinking about, worried about or concerned about, at least over the last ten or fifteen years, overlaps with the stuff that a lot of people are thinking about, worried about and concerned about.

But my first novel, Moth Smoke, for example—when it came out it was not clear that anybody would be at all interested in a novel about pot-smoking adulterous Pakistani urbanites.

“Whether you’re a Sufi poet or a contemporary neuroscientist looking at the brain inside a magnetic imaging machine, what your realize is that the self and what we perceive are constructs.”

I’m somebody who lives between cultures, between Pakistan, America and Britain. The conflict along those fissures is a conflict that reverberates geopolitically. It may not be so much that I have my finger on the pulse of anything but rather that people like me are at the intersection of lots of different developments that involve many different people.

Let’s get to your book selections. I’d like to start with No Longer At Ease by Chinua Achebe. Please tell us about it.

I read No Longer at Ease when I was going to school in Pakistan. It was the first novel by an African writer that I had ever read. In some sense it felt familiar. The main character leaves Nigeria, goes to study in Britain and is, as the title suggests, no longer at ease. It’s a novel that stayed with me, in part because it broadened my sense of who could write literature and what literature was supposed to be about.

No Longer at Ease explores not just moving to a country but leaving a country and returning. The dynamic of somebody who moves in two directions—abroad and back again, was of real interest to me, as someone who had done that myself. I’ve bounced to and from Pakistan and America, and other places as well. The sense that we’re changed by migration—that home is no longer the same because we are no longer the same—was very powerful in that book and that’s part of why it sticks with me.

One critic characterized this book as an ethnic bildungsroman. It seems to me that The Reluctant Fundamentalist could also be characterized that way. Was No Longer at Ease a direct influence?

So often the novels of migration that we read are the stories of migrants coming to one country and staying there. The Reluctant Fundamentalist isn’t that. It’s a story about not just immigration but emigration, return and the responsibility associated with return. In that sense, No Longer at Ease was a precursor—but not necessarily one that I had in mind as I was writing.

The main character goes abroad and his home village finances his journey, in the hope that a British education will empower him to undermine British colonialism. Does transnational literature share the same motivation as this main character and his supporters—advancing critiques of globalization?

What is interesting is that the book is ultimately about complicity. This character dreams about undermining colonialism but, in the end, after a career during which he resolutely refused to take any bribes whatsoever, he finds his life destroyed for taking a tiny bribe. This novel is about how we end up entangled in what we try to resist.

Let’s move on to A Moveable Feast. It’s based on journal entries from the 1920s, which Hemingway dug out of a steamer trunk in 1956 and stitched together in the last years of his life. It was published posthumously in 1964. Tell us about it and its connection to our topic.

We think of Hemingway as an American writer, but much of his writing is set outside of the United States, just as much of his life was set outside of the United States. Farewell to Arms was set in Italy and Switzerland. For Whom the Bell Tolls is set in Spain. The Old Man and the Sea takes place in the Caribbean.

A Moveable Feast takes place in Paris. It’s Hemingway’s memoir of the time he spent there with his first wife and it was stitched together by his last wife. It gives you the sense that he yearns for his first wife and the time when they were young together in France.

“One never gets the sense that Hemingway questions whether he can or should be in Paris. There seem to be no visa issues or racial questions.”

It is important to this topic for a couple of reasons. One is that it reminds us that not all transnational stories move towards America. There is a long and illustrious tradition of literature about moving away from America. Hemingway is changed in important ways by his time away from America. The title refers to the change that Paris works on him. It’s a “moveable feast.”

This memoir is often considered emblematic of the expatriate experience—as life for whites in other nations is defined. How does expatriate literature relate to what we now call transnational literature?

Very often transnational literature is concerned with abrogating an implicit border of belonging. And very often it concerns the question: Does one have the right to be where one is or where one wishes to be? But in A Moveable Feast one never gets the sense that Hemingway questions whether he can or should be in Paris. There seem to be no visa issues or racial questions. Perhaps there is a sense of entitlement to the expatriate experience that the rest of transnational literature lacks.

At the same time, it’s a book about a border that cannot be crossed—the border between past and present. Hemingway is reaching back into his past. It turns out even our most manly of writers can be wistful.

Speaking of remembrances of things past, Henry Louis Gates Jr. called our next author “a Proust in Pakistan.” Tell us about Sara Suleri’s 1989 memoir Meatless Days.

Meatless Days refers to a time in Pakistan, immediately after independence, when the state was struggling to survive. There was not enough meat; so to stretch supplies it was decreed that you couldn’t buy meat on certain days of the week. This occurred as Sara Suleri was growing up in Pakistan, as the daughter of a Welsh-born professor of English and a very famous Pakistani political journalist. So this is a memoir of life in Pakistan as this new nation was finding its feet.

“I see myself as multi-territorialized; it is not that I don’t belong to any territory, it is that I have a sense of belonging to many territories.”

I first read this book as a college student in the United States. Reading about Lahore in a memoir by a Yale literature professor—who was reflecting back on her own youth in Pakistan—had a strange effect on me. It was like being caught in a hall of mirrors. There I was in America, reading about Pakistan, where I come from. It hit me with an enormous sense of nostalgia and also admiration for how Sara Suleri combined the strands of politics, autobiography and cultural criticism.

So Suleri had been de-territorialized by birth, migration and education. How have your life travels influenced your literary reflexes?

I suppose I too, to a certain extent, have become de-territorialized by my life journey, living in so many different places. But, to me, the word de-territorialized suggests someone who is free of place. I see myself as multi-territorialized; it is not that I don’t belong to any territory, it is that I have a sense of belonging to many territories. In Sara Suleri’s work you see something quite similar. She is of New Haven and Lahore. Suketu Mehta, a wonderful writer and a friend, says that people who migrate don’t become multinational they become multi-local. I think that is true of Sara Suleri and myself. All of the places I’ve been have accreted onto how I write and who I am.

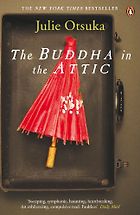

Let’s move on to a contemporary work of fiction. Please give a precis of The Buddha in the Attic by Julie Otsuka.

Julie Otsuka’s novel is an amazing first-person plural account of the mass migration of what were called Japanese ‘picture brides’ in the years leading up to, and during, World War II. It is a story about a group of women told in a voice that is quite unique—the voice of we. It is not a narrative of generalities. It is composed of composite individualities and particularities. It depicts what drove these ‘picture brides’ to leave Japan, what sort of lives they forged when they arrived and their internment during World War II.

Like Otsuka, you play with narrative perspective in your work. Describe how you do that in How to Get Filthy Rich in Rising East Asia and help us understand the potency of perspective as a literary tool.

I’m always looking for the right form for a story. Usually I spend several years trying to write my stories and failing before I find the right form. How to Get Filthy Rich in Rising East Asia had the form of a self-help book. It explains how you can get rich in rising East Asia, the self-help form frames the novel. There are multiple reasons I wrote it that way.

“You see the rise of nostalgic, nationalistic, tribalistic movements in not just Afghanistan or Pakistan or Syria, but also in America and Britain.”

Among those reasons was my desire to interrogate the notion that we read literature because it’s good for us, because it’s supposed to teach us about the world or about ourselves. If that is what literature is supposed to do, I thought: Why not be explicit about it? I also chose that form to explore whether self-help is possible through the practice of reading literature. So it is simultaneously a cynical examination of the way literature is marketed and a true believer’s exploration of what literature does for readers.

The final book you selected is the earliest—a seventeen-piece collection of prose Borges published in 1944. Tell us about Ficciones.

When I first read Jorge Borges, I was amazed by what I encountered. Borges explored how stories work by situating us inside the analysis of a story. In this book, you have essays about a work and world of literature that exists only in the imagination of Borges.

There is a transnational quality to Borges’s writing. He has references rooted in Europe, Africa and Asia in a way that is so audacious as to be unprecedented. He wrote about the world and from a global perspective at a time, pre-internet, when it was difficult to do.

Borges famously saw literary realism “as an impoverishment of fiction’s possibilities and falsification of its artistic character,” according to critic Naomi Lindstrom. Can we credit Borges and his labyrinths as a direct inspiration for the magical portals, which are a kind of killer app for the nation-state, in Exit West?

I was always attracted to writers who created an emotionally impactful and honest experience while writing free from the boundaries of consensus realism. I don’t think consensus reality exists. Whether you’re a Sufi poet or a contemporary neuroscientist looking at the brain inside a magnetic imaging machine, what you realize is that the self and what we perceive are constructs, stories that we construct. Borges realized this as fully as anyone. Certainly Borges was one of the pioneers of what became magical realism.

Get the weekly Five Books newsletter

In my own writing, up until Exit West, I’ve worked with plausibly realistic narratives inside of unrealistic frames. For instance, the story at the core of The Reluctant Fundamentalist is framed by an implausible conversation. In Exit West, for the first time, I’ve knowingly bent the laws of physics inside the main story of the manuscript itself.

You are writing and living in Pakistan, where terrorist incidents upend the city with devastating regularity. You have also written and lived in Britain, where Brexit upended the political landscape in the summer of 2016. Earlier, you wrote and lived in the U.S., where the presidency of Donald Trump is upending American political norms. How do you think the changes roiling the world will reshape transnational literature?

For a long time, the notion that there is a center and a periphery—in literature, economics, politics and culture—has been under threat. Cities like London and New York, the center for so long, are now experiencing problems once associated with the periphery, places like Pakistan. You see the rise of nostalgic, nationalistic, tribalistic movements in not just Afghanistan or Pakistan or Syria, but also in America and Britain. You see politicians trying to undermine the press and intimidate judges, not just in Pakistan and Afghanistan and Syria, but also in America. We are seeing echoes from place to place that we are just not used to seeing. This is perhaps a new era of globalization; the problems of the periphery are now transnational.

Five Books aims to keep its book recommendations and interviews up to date. If you are the interviewee and would like to update your choice of books (or even just what you say about them) please email us at [email protected]

Five Books interviews are expensive to produce. If you've enjoyed this interview, please support us by donating a small amount.