You started your New York life as a fact checker at The New Yorker and became known as a literary man about town after the success of Bright Lights, Big City. But in the 1990s you moved to Tennessee. What drew you back?

I never actually pulled up my roots. I alternated between New York and Tennessee when I was married to a Tennessean. I could never really leave New York because New York has excited my imagination ever since I set foot here. But after the 80s, I needed a little bit of a break.

What about the city excites your imagination?

So many fascinating people are drawn to New York. It’s the world capital of ambition and creativity. People come here from all over the world to pursue their dreams, whether they are dreams of fame, power, artistic achievement or financial gain. I love it because I never know what I’m going to encounter when I turn a corner. To me the sidewalks are teeming with characters I want to write about and the streets are littered with stories I want to tell.

Before we begin talking about the five New Your novels you’ve chosen, I wanted to ask – do you think New York has a distinct literary tradition?

It wasn’t until the early 20th century that we began to develop a distinct New York literary tradition. A lot of American fiction is concerned with the hinterlands. Henry James did some writing about New York – Washington Square, of course – but he famously rejected the United States as being too uncivilised for literary fiction. It was only through his friend Edith Wharton that New York began to find a voice for itself.

Let’s begin with Wharton’s 1905 bestseller. The House of Mirth depicts the manners and morals of turn-of-the-century New York society. Please introduce this classic to those who haven’t read it.

The House of Mirth doesn’t take place entirely in New York but it begins and ends there. Lily Bart, the heroine of The House of Mirth, was born on a higher rung of the social ladder than where she ends up. She is a compelling and tragic figure. The novel was very much concerned with the high society of the day, which was centred in New York – the famous 400 who fit in Mrs Astor’s ballroom. But even though it is concerned with a caste system that no longer exactly exists, The House of Mirth still resonates with readers.

With Wharton, it’s all so well wrought. You can feel the fabric of late 19th century New York and the social claustrophobia that existed behind the heavy drapes of its drawing rooms. But I wonder, why are readers so attracted to stories about the injustices of the upper class when we value social fluidity so highly?

Americans are always fascinated with the wealthy. It’s a bit of an illusion to imagine ours to be a classless society, as novelists like Wharton made brilliantly clear.

Let’s move forward to the New York of 1949. You’ve said that our cultural landscape would have been different had JD Salinger not come along. Please explain.

Catcher in the Rye injected a fresh idiom into American literature. This happened several times in our literary history. Mark Twain in Huckleberry Finn and Ernest Hemingway in The Sun Also Rises did the same – they brought the contemporary spoken language into literature. When Salinger invented Holden Caulfield he gave his voice such freshness and vibrancy. Salinger also almost invented the concept of teenage angst – Salinger’s was the first voice of the youthquake that transformed our society in the 50s, 60s and 70s.

Woody Allen told me that he occasionally reread The Catcher in the Rye because it “resonated” with his fantasies about the city. What does the novel capture about mid-century Manhattan that makes it so memorable for so many?

That makes perfect sense to me, because it often seems that in Woody Allen’s movies he’s trying to preserve the New York of the immediate post-war years. Reading Catcher in the Rye made me want to live in New York City and go to the bars where Holden went and walk in his fictional steps through Central Park. For all of its satire, Catcher in the Rye is a very romantic portrait of New York.

But mostly a portrait of mid-to-uptown. Now let’s head downtown and to the New York of the 1950s that Dawn Powell captures in The Wicked Pavilion. Please tell us about the novel and its author.

The Wicked Pavilion wonderfully reinforced my romantic notions of the bohemian life in Greenwich Village during the mid-20th century. Even while she satirises these writers, artists, models and hangers-on, Powell makes you want to be there, with them, at the Café Julien. I find it a very romantic vision of downtown.

You mention that the book describes how its characters cross paths at the fictional Café Julien. How important are bars, cafes and restaurants to the life and literature of the city? And what are the Café Juliens or Odeons of our age.

You mention the Odeon – that was a real gathering place for a tribe, akin to the one that Powell portrays, in the 80s. Of course there was Elaine’s, the ultimate literary hangout. Elaine’s was a place where writers and intellectuals were the stars, even more than actors and politicians. A few years ago, Waverly Inn was that kind of place. But I can’t think of any place that fills the bill at the moment, but maybe it’s just my age. Perhaps the Lion or Minetta Tavern.

What function do these places play in making New York happen?

We come to the city to mingle and rub shoulders, not to stay in our apartments. If you’re going to just stay inside you might as well move to some place that is cheaper per square foot. We’re paying a premium for proximity to places outside our front door where we can find like-minded others, where we can find romantic partners, where we can preen, show off and watch other people do the same. That’s the point of New York – to see and be seen.

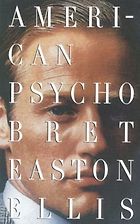

Next let’s flash-forward to the late 1980s and Bret Easton Ellis’s American Psycho. Tell us about it.

It’s a brilliant satire of greed and the mindlessness of popular culture, of American life and of New York in the 80s. It’s a very thorough catalogue of the fixtures of urban existence in that era. This is the anti-romantic novel among my five books. It says that New Yorkers are so busy trying to get ahead that they don’t even notice when people are being killed next door. The killer in their midst, the main character, Patrick Bateman, is described by others as banal, boring. American Psycho was very controversial at the time because of its violence, but I think it’s a novel that justifies its violence.

You, Ellis, and a few of your contemporaries were called a literary “brat pack” by the press. How did what your pack wrote impact on the New York novel?

When I published Bright Lights, Big City in 1984, it didn’t seem that there was a New York novel. It had been a very long time since anyone had succeeded with writing about New York. David Epstein, my publisher, told me that although he liked my book he thought few people would be interested in New York as a literary subject. It had been quite a while since any book about the city had attracted a lot of attention.

“We come to the city to mingle and rub shoulders, not to stay in our apartments – if you’re going to stay inside you might as well move to some place cheaper.”

After Bright Lights, Big City, suddenly there were dozens of novels by young writers set in New York. I like to think I helped to revivify the New York novel and inject it with fresh aspects from the contemporary culture. My publisher also said to me that nightclubs and cocaine were hardly the material of literary fiction. At the time, the subject matter of Bright Lights, Big City was deemed to be beneath literature. But the book was popular and it spawned a lot of imitations.

Finally, The Fortress of Solitude takes us outside Manhattan. It begins in a part of Brooklyn now known as Boerum Hill, but back before it took on its gentrified character and name. Tell us about Jonathan Lethem’s book.

Lethem was one of the first people to write about the new Brooklyn. Like Catcher in the Rye, Fortress of Solitude was a beautiful coming-of-age novel infused with references to the popular culture of the day.

You’ve called Lethem’s work “brownstone and bodega realism”. Are outer-borough writers changing the trajectory of the New York novel?

A lot of the writers who come to New York now settle in Brooklyn as the result of economics. The prosperity of the 90s and the early part of this century might have been good for Manhattan in some ways but the boom meant that many of the most creative migrants to the city are settling in Brooklyn and even other boroughs. I’m sure that will affect the development of New York novels.

How did the 9/11 attacks change New Yorkers and the novels they write?

It’s very hard to write about New York without reference to that event, which was the most dramatic event to occur in New York history since at least the Civil War Draft Riots in 1863, and maybe ever. Norman Mailer once said to me, “You should wait 10 years before you write about September 11.” I chose to ignore that advice, with The Good Life, because I wanted to capture the texture of the emotional response to that event, which is fading. But I’d like to think that someone out there, someone who did wait 10 years, is going to write a novel that addresses September 11 in some great way.

Did the attacks change the city a lot and indelibly?

Not as much as we thought it would. In the days after September 11, we used to hear that nothing would ever be the same again. We all briefly imagined that our lives would be transformed. Some people did change. They changed their jobs; they left their spouses. And then, of course, there were those who lost loved ones and were deeply affected forever.

I do see some positive cultural change. I think New Yorkers are much more aware of their fellow citizens. When I first came to New York people wouldn’t make eye contact – they would literally step over bodies and they walked through the city with tunnel vision. Now people are more aware, more alert and more willing to play Good Samaritan. Now people are more likely to look at each other in subways and in elevators, partly because they’re wondering whether the person next to them would pull them from the rubble or maybe because they’re wondering if that person could be carrying a bottle of anthrax. But regardless of what prompts this interest in others, we’re all a little less self-involved.

Interview by Eve Gerber

September 11, 2011. Updated: August 11, 2023

Five Books aims to keep its book recommendations and interviews up to date. If you are the interviewee and would like to update your choice of books (or even just what you say about them) please email us at [email protected]

Five Books interviews are expensive to produce. If you've enjoyed this interview, please support us by donating a small amount.