As an expert on horror, what would you say is the reason why so many of us enjoy reading scary books or watching films that utterly terrify us?

Part of it has to do with managing fear. With horror novels and films, you know you’re experiencing fear in a safe space that you ultimately control. If you go to a cinema and you don’t like what you’re watching, you can walk out. With a novel, you can just put the book down if it’s too much for you.

What we normally call fear is such a complex experience, especially when it comes to reading. Film operates differently—it can shock you viscerally by having loud sounds or certain types of editing. With reading, it’s a lot more about the imagination. You bring yourself into horror. In a sense, what scares us most about horror is often ourselves, where our minds will take us, which is coloured by our experiences and tastes.

You have written extensively on horror and the gothic, both in literature and film. You’ve also edited a literary history of the horror genre which will see its paperback edition later in the year. Could you tell me a bit about that?

I put together Horror: A Literary History in 2016 after the British Library contacted me with the exciting idea of a lavishly illustrated volume on the topic. It was originally a side project that I developed purely for my love of the genre, as a love letter to it, in fact. All histories are always partial, so my aim was not to provide a definitive tome (this would require many volumes), but an introduction that could be enjoyed by both aficionados and beginners. I wanted to bring academics together from different disciplines who would be able to offer their own unique research-influenced insights.

“In a sense, what scares us most about horror is often ourselves, where our minds will take us”

I was very keen to work with writers like Roger Luckhurst, who knows the turn of the century very well, or Dale Townshend, who is a specialist in Romanticism. I wanted to see how they could bring their own expertise to specific periods of horror writing. The book seems to have sold quite well, helped raise the profile of horror and inspired people to read more of it, which is one of the things I aim to achieve with my research.

What were the considerations behind your choices of scary books here?

It was very difficult. There are so many options. In the end, I chose books that affected me in a particular way—books that changed the way I see the world. Fear is a very intimate thing so it’s very likely that this top five are the books that most scared me personally.

Let’s look at your first choice. This is The Haunting of Hill House by Shirley Jackson. Can you tell us about this book?

The Haunting of Hill House is a story about Eleanor, a woman who lives with her mother and leads a very domestic life. She is called in to assist a paranormal investigation at Hill House, a place where various supernatural phenomena have apparently taken place. People have died there. As the novel progresses, she finds herself almost possessed by the building. One of the scariest things is that you don’t know whether Eleanor was in fact possessed or not. It’s as much a story about physical haunting as it is about psychological haunting. This is one of the reasons the novel is so hard to film; it’s difficult to transpose thought into images. The Haunting of Hill House Netflix series of 2018 did it quite well with one of the episodes, ‘The Bent-Neck Lady,’ which attempted to visually capture the experience of reading the novel.

“It’s as much a story about physical haunting as it is about psychological haunting”

I think the real test of horror fiction, and all fiction in general, is whether you can read it again and still get something new out of it. Shirley Jackson was such a gifted writer; she never really tells you what to think and she never fills in the gaps for you. You have to do that work. The first time I read The Haunting of Hill House, I was so utterly confused by the story. Things happen so fast throughout and Jackson doesn’t dwell on them. You almost have to do a bit of a double-take—did that happen? Who else saw it? Is this person a reliable narrator? Most of Shirley Jackson’s characters aren’t. That sense of discombobulation is quite unique to her writing. Very few of her novels have rounded-up conclusions.

As you say, this character of Eleanor is very psychologically complex. She’s very eccentric—if not neurotic—and this blurs the lines between obsession, paranoia, and susceptibility to suggestion on the one hand and being the victim of genuine supernatural menace on the other.

Absolutely. So many of Shirley Jackson’s characters are like that. The character in The Bird’s Nest also has that multiplicity and unreliability about her. Hangsaman is another great example. In it, a young woman is so traumatised by her college experiences that she may have entirely hallucinated her best friend. What I find so interesting about Jackson’s characters is that their predicament and quirkiness is what makes us like them.

Take the teenage ‘witch’ in We Have Always Lived in the Castle. She may be a scary pariah to everyone else, and with good reason, but it’s hard to read that novel and not be bowled over by Merricat’s idiosyncrasies. She represents the silly rituals we surround ourselves with as we grow up and try to make sense and influence the world around us. Neuroses amplify what’s at the heart of horror stories where the scariest aspects are external circumstances, usually social inequalities and ideological impositions.

There’s a lot of scholarship on this novel with an idea to the ‘female gothic,’ insofar as Jackson is exploring the female psyche in the experience of being manipulated and made to doubt one’s own sanity.

Yes, indeed. One of the things I teach at university is the female gothic. It was a hard choice to pick between this novel and other favourites: Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca, or the play Gaslight, by Patrick Hamilton. They all share the horrors of the manipulation of women by men.

What’s interesting about Shirley Jackson is that she doesn’t try to portray her characters as purely naive or innocent. Hers are well-rounded characters with complex psychologies that you can believe in. But yes, this is a novel about a woman who is ultimately deeply affected by her relationship with a very controlling mother and the not very nice men who use her psychic abilities for research purposes. I think it’s one of the most brilliant attempts at updating the earlier female gothic tradition which, with Ann Radcliffe, Charlotte Brontë and du Maurier, was already quite ghostly but explainable—the horror is eventually reasoned out of the stories. Shirley Jackson plays with ambiguity a lot more.

Next on your list is It by Stephen King—a book he described as like a “final exam on horror.” This introduced Pennywise the clown to the public consciousness.

It was very hard to choose only one Stephen King novel. Although I’ve never written specifically on him, King is one of the writers that had the most impact on me growing up. His sprawling storytelling has been compared to that of Charles Dickens, and I think his novels certainly provide huge mosaics that synthesise the dynamics of twentieth-century small-town America.

Get the weekly Five Books newsletter

It is a novel about a group of teenagers (The Losers Club) growing up into adults, and the disappointments that come with this process. But then there’s this creature—an alien entity—that can morph into your worst fear, with Pennywise the clown the main recurring embodiment (and who doesn’t find clowns a little scary?). The novel explores their relationships coming together later in life and their communal effort to expel ‘It.’

It’s a novel that touched me in many ways. I found Pennywise as scary as it gets, especially its ubiquity and unpredictability. I read It the same summer I watched the TV adaptation with Tim Curry, which is spectacularly well done. I must have been 15 or 16, which is the right time to engage with it too. There is something about the nature of children’s fears in particular that I just couldn’t get out of my head. I think it’s a very well-structured novel that is also a complex analysis of coming of age, of how that process involves leaving things behind, losing people, life not always turning out the way you expected. But there’s also the hope of rekindling friendships, of love and understanding.

And alongside these themes of nostalgia and friendship, there’s also social commentary on less supernatural evil. You have this alien creature It, but it’s juxtaposed with racism, homophobia, child abuse, domestic violence, and psychological trauma as well.

Yes, absolutely, to the point where It becomes something that enhances and feeds off that violence. I think that’s one of the reasons why the novel is called ‘It’ and not something more determinate. Really, it’s a conglomeration and encapsulation of all of that—all forms of hatred and fear. And things like homophobia and racism are always based on prejudice and lack of knowledge of the Other.

One of the things about the novel compared to some of the adaptations is just how strange it is. The creature It has a very complicated mythological backstory and you have things about ‘macroverses’ and a turtle that may have created the universe. Linking it to your next book choice, are we seeing the DNA of H. P. Lovecraft here?

Stephen King has often said that Lovecraft was a big influence on him. ‘Crouch End,’ one of his short stories, and the novella The Mist evince this. So, yes, there’s this complex mythology behind the alien, perhaps as an attempt to ground It as a material creature. At the same time, It takes the shape of your own personal fears, whether that’s a mummy or a fountain of blood. Like fear, It is amorphous and malleable.

Let’s take a look at H. P. Lovecraft’s own work then. Tell me about his Tales.

I know that for some people Lovecraft might be scarier for his racism. Some people have even argued that his racist discourse is one of the things that filters through the way he writes about the alien Other. These are very valid points, and certainly explain his complex reception, with his profile gradually rising from obscurity to recognition and then to disdain.

Ultimately, the message in his stories is that the human does not matter. Lovecraft’s is a very cosmic, materialist way of understanding the world. I like to think of him as a ‘pulp’ modernist. His stories are very much about the difficulty that we have, whether it is linguistic or perceptual, to really understand or capture anything outside of what we know through our senses. His characters go mad or struggle to convey their fear. They can only ever offer partial explanations or descriptions.

That’s another reason why I think it’s so hard to adapt Lovecraft stories into films. Much of the fear in his writing comes from describing things obliquely, through parallels, through things that look like other things. His way of writing is cumulative and works in crescendo. I think the closest writer to him is probably Poe. For some people, his writing is really grating—they find it to be purple prose. There are too many ‘eldritches’ and ‘hideous stenches.’ For me, his writing really creates tension and shock. I think Lovecraft was a master of suspense, among other things

Do you think Lovecraft himself has an optimistic streak? Or it just nihilist cosmic indifference?

His view is not necessarily a popular or a widely shared one. And when you drill down, it can be quite horrifying if you believe in the inherent good and purpose of humanity. The idea is that we’re just some speck in the universe that doesn’t matter. You can look at everything we’ve ever done and admire our technology and capacity to adapt, but in the long history of the cosmos we’re just a small evolutionary accident that will eventually die out. Lovecraft was an atheist and ahead of his time in his thinking.

The best way I can visualise his viewpoint is that 1968 picture, ‘Earthrise,’ that was taken from lunar orbit. Our planet looks so vulnerable, seen from space. I think this was the first time in history when we looked back at ourselves and truly realised that our little planet is adrift in the void. This is, I think, Lovecraft’s vision of humanity and what makes his writing so frightening. For some people, it really works; others won’t be able to get past what they will perceive as misanthropy.

Lovecraft also creates these elaborate and expansive alien mythologies. Can you give us an example of the sort of creatures we find in his work?

The more physical ones are great amalgams of animals and substances that don’t belong together. There are hints of an octopus here, an insectoid touch there. They’re always sums of parts that defy our sense of perspective and order. And then, there’s the issue of not being able to describe them.

I’ve always found the specifics of Lovecraft’s mythological creatures less interesting than the reactions his characters have to them. One of the gods in Lovecraft, Azathoth, is meant to be the god of primordial chaos. It’s described as an “amorphous blight of nethermost confusion which blasphemes and bubbles at the center of all infinity”. It’s a very suggestive idea, almost expressionistic or surreal, rather than concrete.

“The more physical creatures are great amalgams of animals and substances that don’t belong together. There are hints of an octopus here, an insectoid touch there.”

Unlike J.R.R. Tolkien, Lovecraft is not interested in providing a complex chronology, or in writing a history of how his deities came to be. He is a lot more interested in the incapacity of the human mind to conceive of the upending of all the scientific laws that govern our experience of the world. Ultimately, one must look away for fear of losing one’s sanity or grasp on reality. It’s a very powerful concept, and one that has been endlessly imitated.

As we’ve mentioned, Lovecraft was a profoundly racist man—a fervent white supremacist—who even wrote poems expressing race hatred. Some have argued that these views are inseparable from the fictional worlds he creates, in the way that his perceived menace of the Other is transposed into the realm of supernatural alien beings. Does that make his work even more disturbing?

It probably does. There’s no doubt, for example, that an intrinsic fear of miscegenation is something that features strongly throughout his writing.

I think you can look at it two ways. You can say that the racist discourse leads to some powerful writing about the incomprehensibility of the Other (i.e., that Lovecraft’s racism allowed him to write about this experiential gap in a way that transcended race and led to great musings about cosmic indifference), or you could say that it underpins his fiction in a non-productive way that simply replicates patterns of exclusion and marginalisation. I would say that both readings have some value.

There must be something there that can be recuperated, because there are contemporary writers who are rewriting Lovecraft from very interesting and progressive angles. There’s Victor LaValle’s The Ballad of Black Tom, which rethinks ‘The Horror at Red Hook,’ and there’s also Matt Ruff’s Lovecraft Country, which is about to come out as a TV series, produced by Jordan Peele. In the latter, the processes of alien ‘Othering’ mediate the profound racism of 1950s Jim Crow America. The novel is necessarily a critique of Lovecraft—for the black protagonists, the white policemen are scarier than whatever weird creature might be roaming the forests—but it also draws on the power of arcane magic and the metaphysical quandaries so prevalent in his writing.

Next up, we have the first half (vols. 1—3) of Clive Barker’s Books of Blood. Clive Barker is the mind behind such 1980s horror figures as Pinhead and Candyman. Tell us about this one.

Until I read Clive Barker, I wasn’t aware that there could be a space for gays or any kind of queer sensibility in horror. I nearly chose Poppy Z. Brite’s Exquisite Corpse, which touched me in a similar way, for this list (though only those with strong stomachs should approach that one!). I like Stephen King very much, but the vast majority of his books are written from the point of view of white heterosexual males. I remember reading Clive Barker’s stories and noticing a sexually active gay couple in one of them. One of the men meets a tragic ending but that’s not because they’re gay—the tragic ending just happens to be inevitable to the narrative. That opened things up for me. I think it’s important to note that the horror genre offers more than fear; it can also offer solace and experimentation, because it’s a genre that transgresses and goes where others won’t.

“Until I read Clive Barker, I wasn’t aware that there could be a space for gays or any kind of queer sensibility in horror”

The thing I like so much about Books of Blood, and what I find so terrifying about its stories, is Clive Barker’s relation to the body. He’s not scared to tear it open; he’s not scared to metamorph it into shapes that are unthinkable, impossible. In ‘The Midnight Meat Train,’ there’s a butcher that stalks the New York subway, making food out of the people who are left behind. In ‘The Hills, the Cities,’ there are two cities that come together as physical bodies made out of its inhabitants and proceed to fight each other. In ‘The Body Politic,’ there are hands severing themselves and staging their own attacks on the rest of the body.

Five Books interviews are expensive to produce. If you're enjoying this interview, please support us by donating a small amount.

They’re all visceral and suggestive images. Barker is a man who is obsessed with mythology and religion as well. A lot of that comes through in his writing, themes of martyrdom, sacrifice and fundamental transformation. With Barker you have a sort of secular form of the gothic that feels very modern and refuses to engage with the neat Manichean divide of good versus evil. His monsters are predominantly likeable or, at the very least, humane.

Barker is credited as a pioneer of the ‘Splatterpunk’ genre of horror. I think some people tend to see horror that incorporates extreme gore as quite low-brow and just based on shock tactics. With Barker you have very intensive and graphic horror—not shying away from bestiality, necrophilia, and extreme violence—but he uses horror as a vehicle for ideas, subversive satire, political commentary. Is that characteristic of all of Splatterpunk?

No, I think that’s quite unique to him and a few others. Kathe Koja, my final book choice, is someone who has sometimes been affiliated with Splatterpunk, despite writing a little later. With Barker and Koja, there’s a metaphysics behind the violence that is perhaps missing from some of the other Splatterpunks. I don’t want to generalise because they were all were doing different things. Some of the Splatterpunk writers were less visionary: their politics were not particularly progressive or interesting. This doesn’t invalidate their fiction, which is fascinating in its resoluteness to test the boundaries of the acceptable. But with Barker, there’s always an expansive aspect. His approach leads to new ways of thinking about our relation to corporeality—its fallibility, but also its capacity for change.

One of his works, the novella The Hellbound Heart, which was made into Hellraiser, explores all of these areas: pleasure and pain as transcendental aesthetic experiences, the limits of the flesh and of our senses. These ideas are very unique to Barker. And there’s very little fat to his stories too. That’s one of the reasons they have passed the test of time. They’re still incredibly effective.

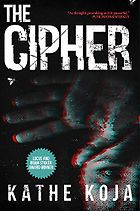

Your final choice is The Cipher by Kathe Koja. It seems to be currently out of print, but a new edition of it is being reprinted in September this year.

Like Barker, there is something about Koja that is simultaneously destructive and creative. She captures the curiosity behind fear. The plot of The Cipher is very simple. A man discovers a small black hole in one of the rooms of the building where he lives. He starts noticing that if you put things through it they return somewhat changed, that something about their genetic makeup alters. Some of them seem to come back with these marks that look like runes—hence ‘the cipher’ of the title. Eventually, by accident, one of the man’s hands ends up in the hole. This moment goes on to fundamentally change everything about him and his experience of the world.

Not much is spelled out for the reader, and yet the novel is so gripping. You feel a mixture of curiosity and fear as you go through it. What could this hole be? What is it going to do to this person? By the time you get to the end, you’re thinking: ‘what am I even reading anymore?’

Given the physical transformations caused by the hole, and the reactions to it, you have this interesting combination of body horror and existential dread.

You’re right. That speaks to my perception of fear more than anything else. I’m terrified by things that shake up who and what we think we are, our certainty. One of the things that come out of Kathe Koja’s novels is the role of art in helping us make sense of the chaos of the world and the unruliness of our bodies—we are creatures in constant flux, in a planet in perpetual change. Stability and order are fantasies we tell ourselves for comfort, and literature and art more generally are creative tools that help us catalyse what we think we understand.

Many of Koja’s characters are artists who are not particularly successful: they may be able to capture something of the strangeness of life, but ultimately, it’s either too much for others or not majoritarian. I think this encapsulates the power of horror in general—how it can shatter our preconceptions, force us to evaluate how we know what we know—but also its limitations, why it won’t appeal to everyone. Many people prefer happy stories that will give them a sense of affirmation, of security. I find horror the most human, powerful and honest of genres precisely because it doesn’t.

This couple are disillusioned with their lives and this nullity becomes magnified by the presence of this literal void that they become obsessed with. There’s a fear of nothingness that really gets under your skin.

I think so. Is it the void of existence? The void of meaning? The silences in their relationship? And yet it is a productive void. It is a void that returns things. It doesn’t just devour them. Objects, animals, body parts—they all come back fundamentally changed in ways that can be no longer rationalised. I suppose we’re back in Lovecraft territory. We have stuff that’s unintelligible, beyond our cognitive powers, and that fascinates me. We’re limited in our perception of the world by the subjective nature of the tools we have at our disposal—our mind, our eyes, our hands. Any attempt at exploration cannot help but be solipsistic. One of the things that horrify me the most are black holes: we still don’t truly understand them, in the same way that we don’t truly understand the cosmos. Neither is ‘evil’, simply currently beyond our comprehension.

A recurring comment about this novel is that it’s disorientating, nauseating, uncomfortable, not only in content but its form in the fragmented nature of how she writes.

I’m glad you mention form. Koja will sometimes mix words together and the rhythm of her sentences is syncopated. They don’t all read like fully formed thoughts. They can be more like fragments or impressions. You can’t skim-read her books, even though her writing is very much a stream of consciousness. You really have to stop and think about referents, meaning and so on.

“I find horror the most human, powerful and honest of genres”

It’s almost modernist in that respect. Koja seems interested in depicting thought—and the language we use to literalise it—as inherently disorientating. There’s nothing more fearful than the mind; it’s where all our fears collect. When you’re experiencing fear through the psychology of someone whose grasp on the world is already compromised by their circumstances, that makes it even more powerful. The scariest of literary horrors are, in my view, not just conceptual, but also linguistic. They activate something personal. And that’s why horror is both shareable and private.

Five Books aims to keep its book recommendations and interviews up to date. If you are the interviewee and would like to update your choice of books (or even just what you say about them) please email us at [email protected]