Can you tell me what the 2022 Walter Scott Prize judges were looking for when they were selecting the best historical fiction of the year?

It’s difficult enough to select the longlist and even harder to render it down to a shortlist. The variety of subjects and styles of the books submitted to the prize increases every year. We are guided by our criteria of ambition, originality, innovation, durability and quality of writing, and it’s helpful to have those guidelines to go by. Then of course we look for that extra something, that pulse of excitement and recognition that a really good book gives the reader. In the best novels we encounter abiding truths about the human condition which resonate with our modern era.

Have you noticed any recent trends in historical fiction, as a genre?

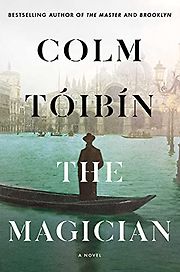

Historical fiction is now so wonderfully varied that it’s almost become hard to call it a genre. The prize is open to writers not only from the UK but from Ireland and the Commonwealth, and every year we’re surprised by the diversity of the authors and their work: the subject matter they choose, the historical context and their style of writing. As for trends—perhaps we’ve noticed an increasing number of what you might call fictionalised biography. It’s sometimes hard to draw the line between biography and fiction, but Hilary Mantel’s Thomas Cromwell trilogy was a perfect example of how the life story of a historical personage can be the starting point for a brilliant exercise of the imagination. The Magician by Colm Tóibín is an example on this year’s shortlist.

Yes, let’s look at the books. Why is Andrew Greig’s Rose Nicolson one of the best historical novels of 2022?

Rose Nicolson is a terrific historical adventure story in the grand old tradition of Robert Louis Stevenson and Sir Walter Scott himself. We couldn’t resist its sheer gusto—the mad dashes down the murky wynds of sixteenth-century Edinburgh, the icy blasts of wind against the granite walls of St Andrews, the thrill of a reiver raid across the border. Andrew Greig brings his characters brilliantly to life: the drooling James VI, the peacock courtier Esmé Stewart, and William Fowler, the main character himself, with all his doubts and fears, his strengths and endearing failings.

It’s set in 1574, seven years after Mary, Queen of Scots, was forced to abdicate. This was a turbulent period in Scottish history. What special insight does Greig’s novel offer us—as opposed to reading a history book, say?

Isn’t this the key question at the heart of historical fiction? Why read a novel when you can read a history book? Surely the answer is that the historian describes a historical personage or period from the outside, being cautious with what isn’t fully known from the record. The novelist takes you directly into the mind and heart of a person from time past, so that you see through their eyes, feel as they feel, and the pieces of the historical jigsaw fall into place around you.

James Robertson‘s News of the Dead is the next work of historical fiction on the 2022 Walter Scott Prize shortlist. What is it about, and why do the judges admire it?

Behind the beguiling, interlinked narrative of three characters from different periods of history—an Iron Age hermit, a nineteenth-century literary conman, and a child thrown out into the world from war-torn Europe—is a profound appreciation of a landscape, the rocks, the rain, the streams, trees and mosses of the remote Scottish glen where these three lives are lived. In our own restless, shifting times many of us have lost any sense of rootedness to a particular place. James Robertson’s novel draws us gently back to contemplate the importance of place and nature in our lives. For many of us, an appreciation of our homes and our surroundings has been one good thing that we will take away from our months in lockdown.

I know Robertson is a fan of Walter Scott because he told me so in an interview on landmark works of Scottish literature last year. He said he was hoping to “emulate the sweep and skill of a novel like [Scott’s] The Heart of Mid-Lothian.” Has he succeeded?

Now there’s a question, and one I find impossible to answer. Walter Scott was the inventor of historical fiction, and any novel which follows Ivanhoe, say, or Waverley, is treading in his august footsteps. Modern authors must all chart their own course. When it comes to skill and sweep, I’d say that James Robertson has scored an ace.

Five Books interviews are expensive to produce. If you're enjoying this interview, please support us by donating a small amount.

Next on the 2022 historical fiction shortlist we have Amanda Smyth’s Fortune. It’s set in 1920s Trinidad. Tell us about it.

I’m not one for technology on the whole, but Amanda Smyth’s novel, which describes the dash and bravado of the early days of drilling for oil in Trinidad, with all the intricacies of machines and derricks and oil pipes, is completely absorbing. Smyth, herself a Trinidadian, evokes the ‘creaking forests’ where the ‘frogs sang their sirens’ with absolute assurance. Her cast of risk-taking oilmen, business investors, anxious landowners and the glamorous woman at the heart of the central love story, hurtle inexorably to the thrilling climax. Fortune is more than an adventure story. It shows the turmoil that the discovery of oil inevitably causes to the settled societies that experience it.

The author, in response to her shortlisting, said that though her “first novel was also historical fiction, [she] had never before now considered [her]self to be a historical novelist.” Interesting! I seem to remember other Walter Scott Prize shortlistees saying something similar in the past. Is there a resistance to the label, among writers, do you think?

I think it’s true to say that for a long time ‘historical fiction’ meant, in the minds of many people, romantic Regency novels, all bosoms and bonnets, a genre particularly enjoyed by women. We’ve moved way beyond that old stereotype now. There is also, perhaps, a perception that a historical novel must be set at a distant time in the past, but the Walter Scott Prize takes as its guide the title of Walter Scott’s first historical novel: Waverley; or, ‘Tis Sixty Years Since. This means that this year any novel is eligible where the majority of the action is set before 1962.

Our final shortlisted historical novel is Colm Tóibín’s The Magician. It’s a fictional portrait of Thomas Mann, author of The Magic Mountain and Death in Venice. Why have you selected it?

The Magician is a magisterial work taking in a wide sweep of twentieth-century history while sensitively dissecting the inner life of one of the greatest writers of his day. A lesser author than Tóibín would have been overwhelmed by the richness of his material, spanning as it does the rise of Nazism, Mann’s need to escape from Germany with his Jewish wife and family, and his turbulent years in America. But The Magician is a novel, not a biography, and Tóibín’s focus is always on Mann himself, his homo-erotic longings, his curious detachment from his unruly children and the way in which he used his own experiences to create his novels.

Get the weekly Five Books newsletter

It’s 500 pages long—I take it the judges feel it’s worth the time investment?

It certainly is! We’ve all read it twice, and I think it’s true to say that we enjoyed it even more second time round. As with any first class book, the more you look, the more you find.

Finally, given your extensive reading, you are in a good place to say: is historical fiction as a whole in a healthy state?

This is a difficult question to answer because historical fiction is hard to quantify. We forget that Tolstoy’s War and Peace was a historical novel, and so was Dickens’s A Tale of Two Cities. We’re finding now that many writers, some with long and distinguished careers behind them, are looking to the past for inspiration, perhaps because our own times are so confused, perhaps because there are so many more accessible and authoritative studies of history, both written and filmed, which are easily available as material. So yes, I’d say that ‘historical fiction’ is indeed in rude health, and is getting stronger and more interesting all the time.

Part of our best books of 2022 series.

Interview by Cal Flyn, Deputy Editor

June 15, 2022

Five Books aims to keep its book recommendations and interviews up to date. If you are the interviewee and would like to update your choice of books (or even just what you say about them) please email us at [email protected]