The Best Philosophy Books of All Time

recommended by philosophers

Last updated: October 07, 2025

After interviewing hundreds of philosophers, these are the philosophy books that come up again and again. If you click on 'expert recommendations,' you'll see what various experts we've interviewed say about each book and why they view it as important.

Many of the books on this list are straightforward reads, that you can enjoy without any prior knowledge. One or two books, while immensely important, are notorious for their impenetrability. In either case, reading one of our experts' explanations of what is significant about a book is nearly always helpful, giving you a tool to navigate the book so you are aware of what parts are worth paying attention to and which are less relevant.

“It contains a tremendous amount of nonsense about what the ideal society would be like. But it is an unmissable book because of Socrates. He invented the method of doing and teaching philosophy that has never been improved on. His persistent questions forced people to spell out their beliefs more fully and precisely, often unearthing beliefs they hardly knew they had. He would then challenge them with counter-examples, putting pressure on beliefs by pointing out unwelcome consequences they had. This questioning is often both intimidating and liberating. Those of us who teach philosophy aim, not always successfully, for the liberation without the intimidation…Some of Socrates’s opponents in The Republic challenge him as to whether there is any reason to be moral, apart from social pressures. They use a simple but brilliant thought experiment. Would you have any reason to avoid wrongdoing if you had a ring that made you invisible, so there was no chance of getting caught? It is not the answers given to this and the other questions in the book, but the absolutely fundamental challenges of the questions themselves.” Read more...

The best books on Moral Philosophy

Jonathan Glover, Philosopher

Plato's Republic: A Ladybird Expert Book

by Angie Hobbs

(If you’re not quite ready to take on Plato’s great work, this is a very short and enjoyable book, with illustrations, that explains the context and introduces the most important topics that the Republic covers, written by a leading scholar)

“I think it’s a remarkable book. The Dialogues were published after he died, though the Natural History of Religion was published in 1757…Hume thought it didn’t actually make much difference whether you believed that God did design the universe or whether you didn’t, because if you could say nothing about this God then it wasn’t a very interesting belief to hold.” Read more...

The best books on Morality Without God

Mary Warnock, Philosopher

“Mencius gives the example of a child falling down a well. He says, ‘When a child falls down a well, what do people do? They don’t just run away, they run towards it.’ They almost can’t help themselves–it’s something they just do. And he observes this and builds part of his moral philosophy on it.” Read more...

Andrew Copson, Nonprofit Leaders & Activist

“The Nicomachean Ethics sets out in a systematic way to answer the question, ‘What is the good life?’ Aristotle wrote it not for scholars, not for other professional philosophers, but for everybody. He took the view that if a person applied practical wisdom to the right course of action in a given circumstance, he would achieve the good. And I like the fact that, as Socrates had done before him, he was thinking about a theory of the good life in terms of what is practical and reasonable” Read more...

The best books on Ideas that Matter

A C Grayling, Philosopher

“What this book does is hammer home one truth. Mill described it as a ‘philosophic textbook of a single truth’. According to him it was hugely influenced by his discussions with his wife, Harriet Taylor, though she didn’t physically write it, and it’s his name on the cover. As the title suggests, it’s focused on liberty, on freedom. It puts forward what’s come to be known as ‘the harm principle’ which is that the only justification for the state or other people interfering with the lives of adults is if they risk harming others with their actions” Read more...

Key Philosophical Texts in the Western Canon

Nigel Warburton, Philosopher

“Not only is Eliot a great moral thinker—you feel the movement of a philosophically sophisticated ethicist moving behind the scenes of Middlemarch—but it’s also about the use of literature in moving us morally forward…It’s not only my favourite philosophical novel, it’s my favourite novel. I teach it again and again and each time I am flabbergasted by what she’s able to accomplish and what my students get out of it.” Read more...

Rebecca Goldstein, Philosopher

“René Descartes is a superb writer who, in his first Meditation (which is the one I’m recommending) takes skepticism—which is an unwillingness to assume anything, a philosophical stance where you question everything—about as far as it can go. Meditations is written as if he is going through a process in real time, he’s imagining himself sitting by a fire taking all the thoughts that he’s had in his past, the different ways of acquiring information, cross-questioning himself about whether he could have been deceived about any of those, and employing what’s come to be known as ‘Cartesian Doubt’. It’s not taking as true anything about which there is the slightest possible doubt. In ordinary life, that’s not a way to behave.” Read more...

Key Philosophical Texts in the Western Canon

Nigel Warburton, Philosopher

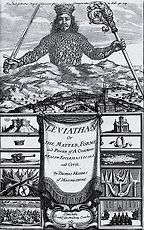

“We continue to read Hobbes’s Leviathan because it very powerfully articulates a particular worldview. It’s an incredible philosophical system that continues to have power in our thinking today. It’s one of the articulations of a theory of sovereignty, for example, that continues to be the key ideology of our interstate global system. There are these systematic philosophical elements that make him a philosopher. But he’s also engaged in the politics of his time and making very particular observations about his own time, his own society, his own culture. There are all of these things that are going on in this text, which is partly why it’s such a rich text. It’s the combination of somebody who is a systematic philosopher, an astute observer of history and society, and who is writing at a time in history that is full of tumult and great transformations. It’s an exciting time and he is an exciting thinker. That’s quite a combination.” Read more...

Arash Abizadeh, Philosopher

“It’s probably the quickest read out of the five books that I’ve recommended. He said in Walden ‘in most books, the I, or first person, is omitted; in this it will be retained.’ There’s this idea that philosophy can blend into memoir and that, ideally, philosophy, at its best, is to help us through the business of living with people, within communities. This is a point that Thoreau’s Walden gave to me, as a writer, and why I consider it so valuable for today.” Read more...

The best books on American Philosophy

John Kaag, Philosopher

“This is the greatest philosophical book of all time. This is Kant’s masterpiece…He’s interested in the limits to what we can know; he’s interested in the limits to what we can use pure reason to ascertain; he’s interested in the limits to what we can even think about. He’s interested in these limits in various different senses. On the one hand, he’s keen to approach them, to map out the limits from within by doing as much as possibly can be done through the exercise of reason; but he’s also interested in stepping up a level and looking at them from above, asking questions of principle about where these limits are to be drawn and what might lie beyond them. Of course, there’s an inevitable problem that arises there because if you’re asking questions about what lies beyond the limits of knowledge then inevitably the question arises: can you hope to know any answers to such questions? For if you claim you can, aren’t you involved in self-stultification? So, all these tensions are there throughout the Critique, and they’re part of what makes it such a fascinating read.” Read more...

Adrian Moore, Philosopher

“It’s not written by Confucius himself. It is more a collection of anecdotes of how he engaged his students, almost in dialogue form. And in them, he comes off as a very charming, humorous figure, not at all dogmatic and very modern. I think that’s partly why he’s been so influential. There’s this view that Confucius was a conformist, but that’s partly because of the way Confucianism has been misused throughout Chinese history… Confucius himself, if you look at his model as an educator, very much encouraged a constant questioning and constant self-improvement and definitely not a conformist attitude to learning. Rather the opposite I’d say.” Read more...

Daniel A. Bell, Philosopher

“Dennett, in this book, is trying to dismiss the dualist intuition completely, to get rid of it entirely. When he says ‘Consciousness Explained’, in my understanding it’s explicable for Dennett because he thinks we are mistaken in thinking that there is anything beyond what is within the realm of normal physical descriptions of mechanisms and their dispositions and their properties. That’s all we need. This book has been a massive influence on me, as has Dennett himself, throughout my career…But I’m not sure I’m entirely convinced by his perspective.” Read more...

Best Books on the Neuroscience of Consciousness

Anil Seth, Scientist

“It has been said that he did extensive research for The Plague. The ‘plague’ is generally taken to be a metaphor or meta-commentary on Nazism during World War II. I’m not necessarily sold on that as the exclusive interpretation of the novel. Other people have argued that he was reading about plagues during the time that he was writing this. But one thing that’s really interesting in the background is that, for at least a period of time while writing the novel, Camus was trying to recover from a bout of tuberculosis and he was staying in a village in southern France in the Free Zone (Vichy). The remarkable events that took place there were the basis for the book called Lest Innocent Blood be Shed by Philip Paul Hallie. In this small, poor, rural village they banded together and pooled their resources to save somewhere between three and five thousand Jews from the Nazis. Camus was in this village as this was happening, as people were hiding, as they were separated from their loved ones, while he himself was separated from his loved ones. So, I’m not sure to what degree the astute nature of his writing can be attributed to his reading about previous plagues, or to his first-hand experience of being bedridden with an illness, embedded in a town where people were hiding from a much more militaristic and malignant sort of ‘plague’.” Read more...

Jamie Lombardi, Philosopher

“This is St Augustine of Hippo in North Africa, which is now in Algeria. He lived from 354 to 430 so at the end of the fourth and the beginning of the fifth century. St Augustine of Hippo wrote a huge amount and he went on a great spiritual pilgrimage from Manichaeism to Platonism and eventually found his way into Christianity. Confessions is a wonderfully personal book, but not in a lurid sense like a modern confession. The whole thing is an almost agonised prayer to God on this kind of search. One of the great things about St Augustine, like so many Christians then, but less now, is that he had a great sense of God as the source of all beauty, as well the source of goodness and truth. There is this wonderful phrase, ‘Oh thou Beauty so ancient and so fresh.’ I think that through The Confessions you get an insight into a passionate mind on a spiritual journey.” Read more...

The best books on Christianity

Richard Harries, Theologians & Historians of Religion

“We chose the book, firstly, because we both love it as a book. It’s a really good example of a book that’s incredibly powerful, and both academically rigorous and accessible. That combination is one of the reasons I think it has been so successful. Another reason I like this book—which ties in with the first, and Manne talks about herself in the book—is that discussions around misogyny or sexism can become so fraught. I think applying this strict, analytical lens to that kind of debate and discussion is very satisfying because it really helps to clarify the concepts that are so often either misconstrued or misunderstood in these kinds of debates. Also, some of the concepts she articulates, ‘himpathy’ being the most notable example, have really caught on in popular culture, which again, I think, is a credit to her innovative analysis.” Read more...

“I chose this book because it’s an incredibly powerful and moving example of what existentialist thought can actually be for in real life, what good it can do, how it can help people. Viktor Frankl was a concentration camp survivor and a psychotherapist and psychologist. Just after the war he wrote a book which has been translated as Man’s Search for Meaning. (The original title translates as Saying Yes to Life Anyway: A Psychologist Survives the Concentration Camp.) In it, he tells the story of his experience and how you can maintain your inner freedom and your human identity in the face of a situation that is designed to completely destroy and demolish all human dignity. It’s almost impossible to do, and he doesn’t say ‘This is the recipe for how I did it’ — he just explores the ways in which fragments of purpose and of meaning in human life kept him going.” Read more...

The best books on Existentialism

Sarah Bakewell, Philosopher

“The Prince is an occasion piece. It was written in 1513 after the Medici had been returned to power. Machiavelli was out of a job—he’d been tortured and fired—and couldn’t afford to live in Florence. And his obsession with politics and international affairs was such that he couldn’t let go. So he started a correspondence with his friend Francesco Vettori and, from that correspondence, arose The Prince. It was a book about how to deal with the crisis of Italy after the French invasions. Machiavelli’s response, in The Prince, was that the only way Italy was going to maintain its independence, and freedom, and drive out the barbarians—which is a term he always used for northern Europeans—was to beat them at their own game, to be more violent, more vicious, more brutal, and more faithless” Read more...

The Best Italian Renaissance Books

Kenneth Bartlett, Historian

“The first task Spinoza set himself in the Tractatus is to undermine the traditional notion of the Bible as the inerrant word of God. He takes the five so-called books of Moses and shows why they probably aren’t by a single person, and certainly not by Moses. As he goes through the various books of the Old Testament, what he’s out to establish is that these writings reflect human ideas, and that they are the ideas of particular people expressed at a particular place and a particular time. Most educated people accept that now, but it was a horrifying idea to the religious establishment in Spinoza’s time…Spinoza thought that the rules by which Jews lived, as derived from the Bible, merely reflected the circumstances of the early state of Israel, and because Israel no longer existed, and times had moved on, he thought these rules had become irrelevant. The dietary laws and so forth that bound the religious community of his time, and which continue to bind the orthodox, were all based, he felt, on a misunderstanding. It was a mistake to suppose that God wanted you to go on living like that even today.” Read more...

Anthony Gottlieb, Philosopher